The Whole South Traduced. In the Matter of Leo Frank.

by Thomas E. Watson (pictured), Watson's Magazine, Volume 21 Number 6, October 1915

ABNORMAL CONDITIONS prevail in this country, and the situation grows more complicated, year by year. We have carried the "asylum" idea to such extravagant liberality, that the sewage of the whole world is pouring upon us. The human race was never known to do, before, what it is doing now, to America. History presents no parallel case. From the Great Lakes to the Gulf, and from Cape Hatteras to the Golden Gate, we see the same ominous, portentous phenomena, of peoples distinct from our people—distinct in language, in manners, in standards, in customs, in National observances.

Huge sections of our over-grown cities are as foreign to us, as any territory that lies beyond seas. Our laws are powerless in these unassimilated settlements. "Little Italy," in New York, is, to all practical intents and purposes, a section of Naples transported to our shores.

Chinatowns in America are miniature Cantons. The industrial colonies of West Virginia, Colorado, Michigan, Pennsylvania and New Jersey, are just that many small Hungarys, Polands, Germanys and Italys. As for the Jews, they have found our "asylum" a paradise; and from the uttermost ends of the earth, they are rushing through our ports. The Zionist Societies, financed by the Hirsch endowment of $45,000,000, are planning to bring 3,000,000 European Jews here, at the close of the present war.

So wide open have been the doors of our "asylum" that the native stock which made the Republic, is already in the minority. Its relative strength grows less with every shipload of immigrants.

Under these torrents of foreign peoples, whole States have lost their original character.

Massachusetts is not what she was before the Civil War, nor is Colorado.

Puritan New England has been submerged. The hordes from abroad are in possession; they fill the shops, the quarries, the factories, the mills, and the offices.

An Ambassador of a foreign nation coolly proposes to his government to tie up the munitions plants of this country, and leave us without means of self-defense!

How? By bribing the subjects of Austria-Hungary to quit work.

An Ambassador of a foreign Nation coolly informs Germans in this country, that they will be punished for treason under German law, if they accept employment from manufacturers who are selling arms to Germany's foes.

It is an open secret that our Government hasn't on hand enough ammunition to supply an army four months, and the Ambassadors of Germany and Austria have demonstrated their ability to lock our wheels, so completely, that we couldn't get, for ourselves from our own plants, the wherewith to defend ourselves from German attack!

If such recent events do not startle our Statesmen into new views of the immigration question, our future will be tragic, indeed.

Where so many elements enter into National life, unusual combinations take place. Strange conditions make strange bedfellows. We have seen the Irish-American Catholics unite with the German-American Protestants against the English.

We have seen the Irish-American Catholic embrace the opulent Jew, against the Protestant.

The Tageblatt (Jewish Daily News) of Chicago, is published in the Yiddish language. Its editor wrote to the Pope, sending the letter through the Papal ambassador at Washington. Bonzano transmitted the communication to his government, the Italian Papal establishment, and in due course, the Secretary of State for Bonzano's government sent the Pope's reply to the Jews, through the Papal Ambassador!

Thus an American citizen, a Jew, placed himself in the position of a government dealing independently with a foreign potentate.

The transaction is so unprecedented that I present the correspondence, as it appears in the Tageblatt of August 25th, 1915:

"The Jewish Daily News is in receipt of a striking communication from Pope Benedict XV, in reply to a request made by us for an expression of opinion on the Jewish question.

The Jewish Daily News Letter to the Pope

June twenty-third, Nineteen Fifteen.

His Holiness, the Pope, Benedict XV.

The Vatican, Rome, Italy.

Your Holiness:—

The denial of justice, aye the deprivation of the very elementary rights inalienable to the welfare of all human beings, has characterized the attitude of the world towards the Jews since the destruction of Jerusalem by Titus. Your heart has been stirred to its very depths by the outrages and excesses committed upon Jewish men, women and children, and we are most sincerely grateful for this expression of horror on the part of your holiness.

Encouraged by the sympathy of the Head of the Church of Christ, we humbly appeal to you to arouse Christendom to a realization of the sufferings of millions of human beings—the Jews—so that they may be accorded—wherever they now lack these—full equal rights and treatment.

Such a call, coming from Your Holiness, will be heeded throughout the world and will meet with the recognition desired.

The Jewish Daily News, the oldest and leading Jewish paper in America, speaking in behalf of the three million Jews in the United States of America, and voicing not only their innermost sentiments, but the views of the Jews the world over, prays that Your Holiness may send through its columns the message that will awaken the conscience of mankind.

Most respectfully and humbly yours,

(signed) S. MASON,

Managing Editor.

This letter was sent to Monsignor Giovanni Bonzano, the Apostolic Delegate at Washington, with the request that it be forwarded to the Vatican.

Monsignor Bonzano has now received a reply, which he has transmitted to us.

Monsignor Giovanni Bonzano,

Delegate Apostolico,

Washington,

TRANSLATION.

The Vatican,

22, July, 1915.

Sir:—I hasten to present to the Holy Father the letter transmitted to me by you No. 18051 D, of the 25th of June, in which Mr. S. Mason, Editor of the New York Jewish Daily News, asked the aid of His Holiness in favor of the Jews who are persecuted and still deprived, in some nations, of full civil rights.

The August Pontiff has graciously taken note of this document and has desired me to request you to write to Mr. Mason that the Holy See, as it has always in the past acted according to the dictates of justice in favor of the Jews, intends now also to follow the same path on every propitious occasion that may present itself.

Yours, etc., etc.,

P. CARD. GASPARRI.

Monsignor Giovanni Bonzano,

Apostolical Delegate,

Washington.

What view will Congress and the President and Secretary Lansing take of the flagrant breach of propriety? What would be thought of a German Society—the Central Verein, for example—if it should open a correspondence through Ambassador Bernsdorff, directly with the German Emperor? What better cloak for a system of espionage and secret treason could be devised, than private correspondence carried on by Austrian and German and Jewish spies, through the Papal Ambassador?

As everybody knows, the President himself would not have written to the Pope, except through Secretary Lansing. But the Jewish organization, which publishes its purpose to carve out a Jewish State in this Union, and its intention to submit certain "propositions" to our Government, has already anticipated its independent existence, by ignoring our diplomatic representatives. It goes over their heads, and deals directly with the Pope, through the Papal Ambassador, just as though the Jewish organization at Chicago were an independent State!

These Jews might be pardoned, for their outrageous breach of loyalty and decorum, on the ground that they do not know any better—but what about Bonzano, the Papal secretary, and the Pope?

They knew better; and they knew they were insulting the Government and people of the United States, when they set the precedent of dealing directly with citizens of this Republic. NO SUCH THING WAS EVER DONE BEFORE!

These insolent Jews take it upon themselves to acknowledge the Italian Pope as the true and only "Head of the Church of Christ."

All Protestant churches are mentally obliterated. There are no Christians save the Romanists. Waldensians, Greek Catholics, and Armenians—all more ancient than Romanists—are left with the heathen. Baptists, Methodists, Lutherans, Presbyterians, Adventists, etc., are mere trash—ephemeral and negligible—in the eyes of the leaders of the three million Jews. The Pope is the earthly embodiment of Christ, the Head of the Church, the one potentate empowered "to arouse Christendom" in behalf of the poor, down-trodden Rothschilds, Belmonts, Guggenheims, Warburgs, Strauses, Ochses, Pulitzers, Abells, Schiffs, Kuhns, Loebs, Montags, Seligs, Dannenbergs, Waxelbaums, and Haases.

With a fine display of scorn for our President and Secretary of State the Three Million Jews slap the face of Diplomatic Etiquette; and with a noble exhibition of contempt for non-Catholic churches, they spit upon the creed of Christianity.

Two years ago, I thought that there were evidences of a league between American priests and the rich Jews of our large cities, and our readers may remember my comments.

There is no longer any doubt that the Roman priests and the opulent Jews are allies.

"The Holy See, as it has always in the past acted according to the dictates of justice, IN FAVOR OF THE JEWS, intends now to follow the same path."

What marvelous liars these priests are! How boldly they presume upon short memories, selfish opportunism, and ignorance of history! They can rely upon the Catholic to believe everything they say, for they know that the Catholic will not read after a "heretic." They are not much afraid of the "heretic," for they know that his readers are indifferent, his churches decadent, his daily papers choked with gold, and his political leaders afraid of the Catholic vote.

Therefore James Church, the Pope, never bats an eye, when he tells the Jews that he means to follow in that path of justice to the Jews, which his predecessors have always trod.

We'll be learning next, that Nero was a great friend to the Christians, that the Duke of Alva protected the Dutch, that Claverhouse cherished an ardent affection for Scotch Presbyterians, that Catherine de Medici flung her queenly mantle over the Huguenots, and that the Hapsburgs of Austria were indomitable defenders of the Reformation.

"The Holy See has always acted according to the dictates of justice, in favor of the Jews!"

Well, well, WELL!

So it is not a Papal Poland that grinds the Israelites to the ground.

It was not a Papal England that outlawed the Jew, nor a Protestant England that enfranchised him!

It was not a Papal France, that degraded the Jew, nor a Revolutionary and Napoleonic France which rehabilitated him!

How long has it been since Pope Pius IX kidnapped the son of the Mortaras to make a priest out of him? All Europe rang with the scandal, and the Emperor of the French implored the Holy Father to restore the boy to his distracted parents. But the Pope was unrelenting, and those Jews never saw their son, again.

How long has it been since modern liberalism compelled the Popes to discontinue their annual custom, at Rome, of publicly cursing the Jews?

How long has it been since the 29th canon of the Aurelian Council was rigidly enforced—the Papal law which made it death for a Jew to even speak to a Catholic during Holy Week?

(See Roba di Roma, by W.W. Story, page 423.)

Who was it that destroyed Jewish libraries, forced Jews to wear badges, forbade them to eat and drink with Catholics, closed all the professions to them, and taxed faithful Jews, to support Jews who consented to change their religion?

Pope Eugenius IV did it.

Who expelled the Jews from all Italy, except Rome and Ancona?

Pope Pius V did it.

Who sent the murderous, devilish Inquisition into Portugal, to first torture and then burn, the Jews?

Pope Clement VII did it.

Who ordered the general destruction of the Talmud, and sanctioned the wholesale massacres of Jews in France?

Pope John XXII did it.

Who ordered the punishment of Jewish physicians for entering Catholic houses, and denied Christian burial to Catholics who employed Jewish physicians?

Pope Gregory XIII did it.

Who controlled Europe during the dismal ages when Jews were hounded like wild beasts, denied human rights, and grudgingly permitted to dwell in pestilential ghettos?

The Popes did.

Who ruled the nations and directed the consciences of monarchs and ministers, during the fearful centuries when a Jew could not own a home, could not hold an office, could not hold up his head among men, and was forced to eke out a squalid existence, on such ignominious terms, and amid such dwarfing conditions, that the Jewish race, even now, shows the physical and moral effects of that long night of slavery?

The Popes did.

Who liberated the Jews from these horrible conditions?

Modern democracy did it.

When Great Britain, less than 100 years ago, removed the Civil Disabilities of the Jews, it was Protestant statesmanship repealing Catholic laws.

Who was the Papal theologian who taught, that "Jews are slaves?"

It was Saint Thomas Aquinas, the chiefest of all Roman Catholic theologians.

For hundreds of years the legislation of Europe was based upon this infernal teaching—the teaching of a theologian who was such a favorite of the recent Popes, Leo XIII, and Pius X, that they ordered all Catholic teachers to again instruct their students in the Papal theology which forfeits the life of the "heretic," and imposes serfdom on the Jew.

(See Barnard Lazare's Anti-Semitism, page 125.)

But how could you expect these historical facts to be known to a Chicago editor, who informs the Pope and the world, that the Jews lost their rights—the natural rights of man—when Titus stormed Jerusalem?

According to the Tageblatt, the Jews have been the pariahs of the human race, ever since the year 70, after Christ! Mason, of the Tageblatt, ought to at least consult some simple authority on Roman history, Merivales's book, for example. It won't take him but a few minutes to learn what an ass he made of himself, when he told the Pope that the Jews had never had a square deal in the world, after Jerusalem fell. If the Tageblatt Solomon will study the subject, he will discover that the real persecution of the Jews began after Constantine the Great had made his famous alliance with the Christian bishops. Solomon may also learn that when the Emperor Julian, "the Apostate," undertook to re-establish paganism, he emancipated the Jews, and attempted to rebuild their temple at Jerusalem. Solomon will learn that so long as Popery was supreme, the Jew was the vassal of the bishops and the kings, and that it was the Reformation which brightened the skies for the outlawed race.

Bernard Lazare, the scholarly Jew, says in his Anti-Semitism, page 131:

"But new times were approaching; the storm foreseen by everybody broke over the church.

"Luther issued his 95 theses * * * For a moment the theologians forgot the Jews; they even forgot that the spreading movement took its roots in Hebrew sources * * * *

"THE JEWISH SPIRIT TRIUMPHED WITH PROTESTANTISM. In certain respects, the Reformation was a return to the ancient Ebionism of the evangelic ages."

Lazare proceeds to prove that although Luther was provoked into violent language against the Jews, because they refused to become his converts, the Protestants of Germany never ill-treated the Jews.

(See page 133.)

In the United States, the priest and the Jew have need of each other and the Pope has blessed the alliance.

That the Hearst papers are leagued with this queer combination of Jew financier and Roman priest, is an interesting detail; whether important as well as interesting, remains to be seen.

In the case of the Russian Jews, the new combination worked so well that our Congress, in 1913, abrogated a time-honored treaty, as a protest against Russia's alleged mistreatment of her own subjects.

Descending to particulars, the new combination was able to save the Russian Jew, Beiliss, who was accused of taking all the blood out of a Gentile boy, through forty-odd incisions in his veins.

In the Leo Frank case, the new combination almost won, but not quite. And, of course, the unexpected defeat it sustained, profoundly enraged the new combination.

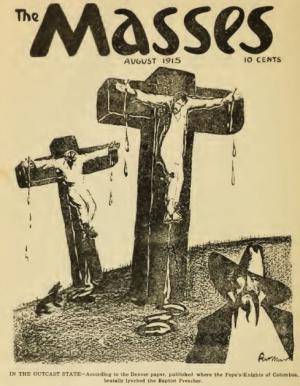

The Roman Catholic papers are as bitter against the State of Georgia, as are the papers of Hearst and the Jews.

The same Romanist journals that condoned and defended the deliberate assassination of the Protestant lecturer, William Black, by the Knights of Columbus, at Marshall, Texas, are unmeasured in their denunciation of the State wherein a convicted and thrice-sentenced Jew was hanged by the Vigilantes.

These Romanist papers indecently exulted in the military murder of Francisco Ferrer, whose crime consisted of teaching progressive ideas in a modern school, but they are rabidly attacking a People who were determined that one of Leo Frank's lawyers should not annihilate our judicial system.

The same Romanist papers that gloried in the burning of eight Mexican "heretics" in 1895, at Texacapa, by the fanatical Catholic priests, can find no words too severe to condemn the legal conviction of as vile a sodomite as ever awoke the wrath of God.

This new combination of rich Jew, Roman priest and Hearst newspaper, has arraigned the State of Georgia, at the bar of public opinion; and so artfully persistent has been the propaganda of misrepresentation, that hundreds of editors and preachers, totally disinterested, have been swept off their feet. These honest, but deluded, defamers of Georgia, have broken the bounds of temperate discussion; and their abuse has become so indiscriminate, that it spares no State in the South, and it calumniates both the living and the dead.

We Georgians, particularly, are a mean, low-down lot, and always were, because our forbears were the sweepings of London jails. Since our ancestors were criminals—a sort of Botany Bay and Devil's Island settlement—it is natural that we should be a disgrace to the Union, and a reproach to the human race.

Even a Virginia paper can bring itself to publish the following:

The guilt or innocence of Leo M. Frank in the matter of the murder of Mary Phagan has absolutely no bearing on the crime committed by these savages in Georgia. Frank had been confined in this prison for life because a fearless Governor preferred to commit political suicide and endure social boycott in the state of his nativity rather than permit the hanging of a man who had been convicted on the questionable evidence of a criminal negro and regarding whose guilt there certainly existed a most reasonable doubt.

Is this in any way surprising? Not in the least bit when we review the history of Georgia. It was originally a penal colony and was settled by the worst felons and perverts that England could export to her blistering shores. Succeeding generations grew up with criminal instincts just as marked and with ignorance, superstition and physical unfitness far more marked. These are the Georgia crackers, the clay eaters among whom hookworm and pellagra and other disgusting diseases run rampant. Not in the entire history of the state has pure Georgia blood produced a really great man. They were cowards and skulkers and camp followers in our Civil War, and that Gen. Sherman should have cut himself off from his base of supplies and marched entirely across the state unopposed is not in the least bit surprising when we consider the caliber of the male citizens of that commonwealth. Its first families have now established what they are pleased to call "society" in their capital city of Atlanta, where they spend their ill-gotten gains acquired through manufacturing nostrums and other quack devices guaranteed to do everything from taking the kink out of a negro's hair to turning the darkest Ethiopians into a pure-blooded Anglo Saxon.—The Virginian.

The Milwaukee Free Press of August 18, 1915, said:

THE SOUTH AT THE BAR.

"The spirit and method of the Ku Klux Klan has once more triumphed in Georgia.

"Once more Southern ‘gentility' and ‘chivalry' have revealed their true character in murder, secession and anarchy.

"For the same bestial spirit that sought to disrupt this Union, the same spirit that lashed and ravished the helpless slave, the same Southern spirit that even today is celebrating the blood-lust of the Ku Klux Klan as a virtue, is living in the persecution and murder of Leo Frank.

"The trial and conviction of this unfortunate Jew, as accomplished by the courts of Georgia, was enough to damn the people of that state as unfit for citizenship. The horrible sequel of his assassination proves them to be something worse than barbarians.

"Americans have gazed askance at the bloody immorality of Serbia. But Serbia is a paradise of civilization compared with the state of Georgia.

"And this is not the worst. The worst is that the spirit that prevails throughout a large portion of the old South. Every Southern state that tolerates lynch law, whose people revel in the writhings of tortured blacks, is capable of Georgia's monstrous outrage. Every community that burns negroes at the stake or hangs them for unproven or petty crimes, would act as Georgia did in the case of Frank.

How can the nation—the civilized, responsible and self-governing part of it—longer tolerate this anarchy, this blood-lust on the part of a section that once defied humanity and government till it had to be broken with swords and bullets?

"And then this rot about the dangers of miscegenation! Who is responsible for the mixture of Caucasian and Ethiopian blood in the country, the negro or the Southern white? Not one light-colored black in 5,000 is the result of a negro's design on a white woman. The light-colored black, with scarcely an exception, dates his ancestry to the lust of some Southern white master, who did not hesitate to make the creature he bought and sold as an animal the mother of his children.

"So much for the Southern hypocrisy that prates of miscegenation to justify its crimes.

"If the cries of the burning black victims of a hundred Southern stakes have not been able to rouse the conscience of the North, can it remain deaf to the last agonized prayer of Leo Frank as his tortured body was swung by ‘Southern gentlemen' from a Southern pine?

"If Georgia cannot be scourged from out the sister-hood of states, if she cannot be reduced to a condition of dependence lower than that of the Philippines, she can at least be visited with a commercial, social and political ostracism which will convince its gentry that true Americans still enthrone justice and humanity as the chief bulwarks of the nation."

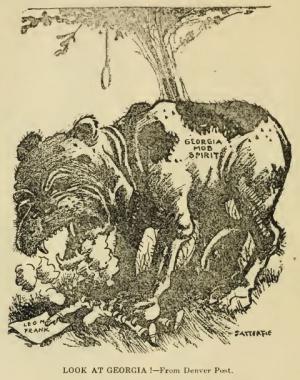

The Wine and Spirit Bulletin is mighty hard on us; it says:

LOOK AT GEORGIA.

As a spectacle fit to make the gods weep we commend to the people of the other States in the Union and especially those inclined to try the experiment of prohibition the prohibition State of Georgia. Georgia stands today pre-eminent in disgrace before her sister States in the Union.

"The professional prohibitionists have a way of tracing to the licensed liquor traffic the blame for nearly all crime in general and for every startling crime or terrible disaster in particular, it remaining for them to even connect the slaughter of the innocents, women and children, as well as men, in the Eastland disaster, with drinking. What then can they say for Georgia, one of their banner prohibition States? And in view of their habit are we not justified in reversing the situation?

"Yet the shameful acts of citizens of the prohibition State of Georgia, in intimidating the court of justice and the jury in the Frank case, in threatening the Governor who had the courage to defy the mob, and their subsequent acts in murdering their helpless victim and making a morbid show of his corpse, are but logical and natural results following the teachings of the prohibitionists and of prohibition.

"Yes, Georgia is disgraced today as the natural consequence of adopting prohibition doctrine, which in its very nature is anarchistic and puts the rule of the mob above the rights of individuals, above courts and law, above constitutions, above human life, even, when they stand in the way of accomplishing its mad purposes.

"Look at Georgia, oh ye citizens of the United States, and then decide whether you want prohibition and its consequences!"

The Chicago Tribune said:

"The South is backward. It shames the United States by illiteracy and incompetence. Its hill men and poor whites, its masses of feared and bullied blacks, its ignorant and violent politicians, its rotten industrial conditions and its rotten social ideas exist in circumstances which disgrace the United States in the thought of Americans and in the opinion of foreigners.

"When the North exhibits a demonstration of violence against law by gutter rats of society, there is shame in the locality which was the scene of the exhibition. When the South exhibits it there is defiance of opinion.

"The South is barely half educated. Whatever there is explicable in the murder of Leo M. Frank is thus explainable. Leo Frank was an atom in the American structure. He might have died, unknown or ignored, a thousand deaths more agonizing in preliminary torture and more cruel in final execution, and have had no effect, but the spectacle of a struggling human being, helpless before fate as a mouse in the care of a cat, will stagger American complacency.

"The South is half educated. It is a region of illiteracy, blatant self-righteousness, cruelty and violence. Until it is improved by the invasion of better blood and better ideas it will remain a reproach and a danger to the American Republic."

The Pueblo, Colorado, Star-Journal said:

"Georgia has added another chapter to its disgraceful story of the Frank case, the climax coming in the cowardly lynching of Leo Frank by an armed mob that forcibly removed him from the state prison farm and deprived him of life near the home of the young girl for whose murder he was convicted by a jury. The lynching of Frank is the logical outcome of the lawless scenes attending his trial and following the change of his death sentence to life imprisonment by a courageous governor who felt that Frank had not been given a square deal. After the attack on Frank by a fellow prisoner it was evident that further attempts would be made to kill him, and the lynching therefore is no great surprise. It was what could be expected from blood-hungry, law-defying demons.

"The lynching of Frank is inexcusable and those responsible for the horrible affair deserve the punishment that should be given to the perpetrator of any deliberate murder. Georgia will merit the contempt of every other state if the murderers of Leo Frank are not captured and convicted by due process of law. This crime against justice ought to arouse every decent citizen of Georgia in an effort to partially blot out the shame of their state.

"Those who doubted the charges that Frank had been unfairly tried will change their opinion as a result of the mob vengeance visited upon him. The same spirit that caused his hanging undoubtedly was present during his trial and resulted in his conviction by jurors who feared for their own safety if they cleared him of the charge of murdering a young girl in the pencil factory of which he was superintendent. The general opinion is that Frank was innocent of murder and should not have been convicted on the unsupported testimony of a worthless negro."

The Denver, Colorado, Express said:

"The assassination of Leo Frank by citizens of the sovereign state of Georgia brought disgrace, not only upon that commonwealth, but upon the entire nation. The arrest, conviction and the final murder of the unfortunate victim of brutal blood-lust will go down in history as the vilest miscarriage of justice ever recorded.

"Taken nearly a hundred miles, the exhausted invalid, handcuffed, was hanged and then, lest Georgia savages should mutilate his mangled body, it was spirited away.

"The wars with the early Indians were marked by scalping and sometimes by burning at the stake. The story of the torture of explorers by savage tribes of cannibals has been written. The perpetrators of this cruelty were savages.

And yet, in this Year of our Lord, 1915, in the Twentieth Century of civilization to the Nth power, a stricken man under the protection of what we are pleased to term the Law, is cruelly assassinated in an organized State. Savages is too mild a term for the Georgia outlaws.

"The stain which the assassination has brought upon the nation can never be washed out. Georgia today is an outcast among the States."

The Chicago Post said:

"If there is self-respect in Georgia, if there is courage in its governor, the men who have dragged its name in the mire of infamy will be found and punished as they deserve—and they deserve hanging. Georgia may resent outside interference, as some local Mississippian suggests, but Georgia cannot be law and license to herself in this matter. Her shame is the shame of the nation. Nor will the old excuse that it was the deed of an impulsive and ignorant mob satisfy. It was the deed of deliberation, not of impulse, and ignorant mobs do not travel in automobiles."

The Boston Traveler said:

"In this crowning demonstration of her inherent savagery Georgia stands revealed before the world in her naked, barbarian brutality. She is a shame and a disgrace to the other states of the Union, who are powerless in the matter of humane justice to put upon her the corrective punishment her crimes deserve. But the consciences of the American people are not so callous as those of the Georgians, who sanction by silence or take part in such crimes against fellow-beings, black and white. And to the degree that a humane public can rebuke the state of Georgia by refusing to have any part of her unholy peoples' products they will do so. Anything made or grown in Georgia will bear a sinister band and be suggestive of lynchings and burnings and especially of this brutal murder of Frank, and it ought to be and doubtless will be left untouched. The only way in which Georgia can be made to feel the shudder of horror which is sweeping the country and the utter contempt in which she is held by the rest of the nation, is by a deliberate boycott of Georgia-grown and Georgia-made goods—peaches, cotton, or whatever else bears the stamp of the so-called ‘Empire State of the South.'"

The Louisville, Kentucky, Herald (owned by a Chicago Jew), said:

"Surely such a state of affairs is the South's shame and Georgia's shame!

"Georgia's shame lies in the city government of Atlanta, which railroaded Leo Frank to an unmerited conviction, in her police force which made him a victim of the demand of an inefficient constabulary to convict someone at all hazards, which turned loose the degenerate Conley because it had made up its mind too soon that it could and would convict Frank.

"The shame of the State is no greater on account of the lynching of Frank than because of any of the other almost innumerable lynchings which have preceded it in that State and others.

"But because of these other things which preceded his conviction, her shame is black and continuing.

"It will continue until it may be said in Georgia that a man may be prosecuted, no matter what his crime or how clear his guilt, without the presence of the police in the prisoner's dock asking for the vindication of a detective theory, and without a press which panders to the lowest passions of the mob by such methods as makes a fair trial and a just sentence beyond the power of ordinary men in the jury box or on the bench to render."

The Investment Magazine, Canton, Ohio, said:

"Thousands of impartial investigators are convinced that Frank was not guilty. Millions have read the evidence and know that he was convicted on "framed up" testimony—and that he did not have a fair trial. But Georgia was determined to "Hang the Jew" and has done so; in spite of law and police protection and all the other apparatus of government.

"The lynching was participated in by the entire commonwealth of Georgia. All right minded men familiar with state prisons know that Frank could not have been taken from his cell without connivance on the part of state officials. If this is not sufficient proof, take that speech in which the Mayor of Atlanta openly gloated over the affair. The meeting was not one of criminals, nor of light minded people in the street. It was a solemn gathering of the Chamber of Commerce. Listen also to the Sheriff of the county, who asserted that he would make no effort to arrest the lynchers because a jury could not be found that would indict them.

"Compared to such a crime, the murder which led Austria to undertake the punishment of Servia was insignificant. Georgia should be punished."

In pious Boston, Massachusetts, the Jews and the Knights of Columbus held a mass-meeting in Faneuil hall, to express their mixed emotions.

As reported in The Globe, the Jews and the Knights said some violent things. For instance:

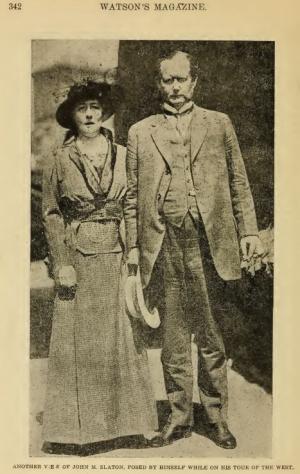

"The next speaker, Dr. Coughlin, ex-Mayor of Fall River, who was a member of the committee that visited Atlanta and met Gov. Slaton, received a warm reception. During his stirring address Dr. Coughlin was continually interrupted by applause.

"Dr. Coughlin said that he had told the other members of the committee who were with him in Georgia that the spirit of the people and the press showed him that if Frank was freed by Gov. Slaton he would be killed by a mob. The speaker lauded ex-Gov. Slaton for his action. He attacked Thomas Watson, the editor of the Jeffersonian, and said it was a disgrace to have the American flag float over him, as he was a disgrace to American citizenship.

"Dr. Coughlin said that he knew that Leo M. Frank died because he was a Jew. He also said that it was not true that race prejudice showed itself on account of outside interference, as is claimed in Georgia. The speaker stated that the stories circulated about the behavior of Frank are not true and are used to cover over the crime of the ones that killed him.

"In closing he said that he did not believe it was going too far when he said that the present Governor and every official in Georgia knew the ones that took part in the lynching of Frank. He pleaded with his audience when they left the hall not to forget to work in aiding in vindicating the name of Leo M. Frank.

"Rabbi M.M. Eichler of Temple Ohabei Shalom, stated that he firmly believed in the innocence of Frank and said that the meeting was both one of protest on account of the lynching and memorial meeting for the martyrdom of Frank. He claimed that Frank never had a chance and received a mistrial because he was Jew and a Northerner. In closing he said that Georgia is not fit to be a sister State of Massachusetts.

"Rev. Charles Fleisher created some enthusiasm when he spoke of boycotting the State of Georgia. He said that it might have some effect to refuse to travel there, to trade there, to loan money there or to spend money there, for he said that if the pocket nerve is touched it will make the State squirm. He also said that, if Germany is wrong regarding the Arabic matter, America should boycott Germany for at least five years and such action would bring results.

"After the addresses Secretary Silverman read the resolutions which were unanimously accepted:

"One of the resolutions declares that the Jeffersonian has ‘aroused hatred among the citizens of the United States and incited the mob spirit among the people of Georgia,' and demands that ‘the United States post office authorities exclude this paper from the United States mail.'

The second resolution was as follows:

"‘Resolved, that citizens of Massachusetts, in Faneuil Hall assembled, denounce the lynching of Leo Frank by a Georgia mob as a deliberate and cowardly murder a high crime against civilization, and a disgrace to the United States, and urge upon their fellow citizens of Georgia, both those who know the perpetrators and those whose duty it is to enforce the laws to redeem the honor of their state and nation and their own past reputation for high-minded citizenship, by bringing those who are responsible for the outrage to prompt and adequate justice.'"

One point stressed in most of these attacks on the South is, that Leo Frank was serving a life term in the penitentiary, and in good faith meant to take his medicine.

The Hearst papers argue it from that point of view, and so do most of the other traducers of Georgia.

Yet every one of these editors know that the Burns agency, the Jew papers, and the Hearst writers had declared that the State "must redeem herself" by granting Frank a full pardon.

The Burns agency blatantly announced that "the fight" was to be immediately renewed; and, since Frank's execution, Burns seems almost beside himself because of the loss of so lucrative a case. Are the editors at all chagrined for the same reasons? Are these virtuous publishers feeling sadly the loss of the Jewish ducats that paid for so much front-page space? During a whole year, Burns, Lehon, and a battalion of lawyers—some in New York and some in Georgia, luxuriated in the Frank case.

The Kansas City Star, the New Orleans Item, the Chicago Tribune, and various other righteous dailies, to say nothing of "farm" papers, have banqueted on the Frank case. When he was put to death according to Law, they had lost a gold mine. Of course, they deplore it. Othello's occupation's gone, unless Slaton's attempt at a "come back" in Georgia reopens the golden vein.

As to that, we will soon know.

Did Leo Frank take the commuted sentence in good faith, intending to serve a life sentence? Did his partisans regard the Slaton commutation as anything more than a prelude to a pardon, or an escape?

Let us see.

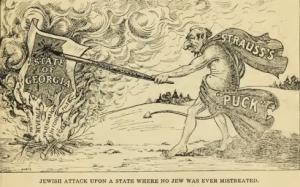

The Straus Magazine, Puck, said:

"All credit to Governor Slaton, of Georgia. His was a noble stand by his conscience and by his convictions against the clamor of prejudice and public opinion.

"Close upon the news of the commuting of Frank's sentence came news of rioting in the streets of Atlanta, of the same mob spirit that has so often resulted in crimes that are a stain upon Georgia's record.

"The fight for the vindication of Leo M. Frank has not ended; and even with his acquittal—and his ultimate acquittal is only a matter of time—the fight for decency in Georgia will only have begun. This fight for decency will not end until low-lived slanderers without moral character, without public spirit, are run out of the state of Georgia. The fight will not be won until men like Thomas Watson, the very embodiment of the beast in looks, manners and conduct, are removed from any influence upon the public sentiment of the community. This creature, whose private conduct is such that we cannot describe it in our pages, will be further exposed as our probe goes deeper."

Burns said:

Ultimately, perhaps in the very near future, Leo Frank will be freed. He will come from the Georgia prison, where he has been since Governor Slaton commuted his sentence of death to life imprisonment, vindicated of the murder of Mary Phagan, and the crime laid on the shoulders of the principal state's witness in the famous trial. Governor Slaton, hissed by mobs in Georgia, will be hailed a hero.

In the New York Evening Journal (Hearst-Jew-Catholic), the Rev. Dr. Charles H. Parkhurst said:

At the time of this writing this young hero is hovering between life and death. The situation is pathetic. We want him to live. The country wants him to live, with the exception of some portions of dishonored Georgia. Our ambition for him goes farther than that. We want to have him restored to the enjoyment of that liberty of which it is the almost universal sentiment he has been unjustly deprived.

It is entirely safe to claim that in the judgment of ex-Governor Slaton, the man is either innocent or unfairly convicted. In either alternative a life sentence or any other penalty is an injustice. Under the circumstances the only course open to the ex-Governor was to commute. Frank's safety lay not in freedom, but in imprisonment. Jail was supposed to be at least a place of security. It was assumed that convicts already immured there, especially if they were convicted murderers, would not be allowed to roam around the jail yard with concealed butcher knives.

If poor Leo lives he will have to possess his soul in patience till the unaccountable bitterness of his persecutors has worn itself out, which it will do in time. Passion cannot maintain itself indefinitely. It is like fire which goes out unless fed with fresh combustibles. We may safely believe that unless he is set free by the liberating mandate of death, he will eventually have freedom given him by the order of the court.

When the New York preachers—Parkhurst, Hillis and others—first butted into the Georgia situation, I wrote each of them a courteous letter, asking them to allow me to put before them the evidence on which Frank was convicted.

Neither of the ministers of the gospel condescended to give me an answer.

The New York Evening Mail published the following:

If Georgia would invite the respect of law-abiding citizens the governor would proceed to pardon without any further delay the man who stands before the whole world as an innocent man, except in the estimation of some Georgians.

Blin, the Boston Jew who had been syndicating articles in Frank's behalf, followed the commuting of his sentence, by publishing a philippic against The Jeffersonian, in which he declared that before any effective move could be made to release Frank from the State Farm, Watson and his publications must be outlawed. Blin stated that certain "gentlemen" were at work on a plan to have the Post-office department issue an order against me.

The son of William J. Burns, in charge of the New York office of that notorious crook, gave out a statement to the papers immediately after the commutation, that "the fight" to secure freedom for Frank was to be renewed at once.

Therefore, the evidence is overwhelming; Frank and his partisans did not take the commutation in good faith. They regarded it as a necessary step to a full pardon, or to an arranged escape.

When Frank reached the State Farm, he was received as a guest of honor. He was given a separate room and his own furniture; his floor was carpeted, and an electric fan was installed. He even had his electric cigarette lighter. A negro convict was assigned to wait on him. His roller-top desk was moved in, and he went to work on his correspondence, preparatory to shaping public sentiment again. Only one day, and not all of that, did he wear stripes, and that was the day the Farm was under inspection. The other convicts were so maddened at the favoritism shown this vilest of criminals, that Creen tried to kill him. Of course, a great uproar followed, and the attempt was credited to The Jeffersonian. It transpired that Creen had never seen a copy of my paper; and, of course, the paper never contained anything inciting to murder.

All the outside papers were astounded that no effort was made to resist the few men who took Frank away from the guards. Is it possible that the editors have not guessed the reason?

There are but two possible solutions: One is that the guards were infuriated at him, and at the double duty they were made to do for him, alone; the other is, the guards believed that Frank's friends were taking him out.

On his night ride to Cobb county, Frank told the Vigilantes that, at first he did not know whether they were his friends, or his enemies.

I may as well state it here, as elsewhere, that Frank did not at any time protest his innocence; but, on the contrary, he said just before he was executed: "The negro told the story."

Then, he added the remark about his wife and mother, a remark which meant he would rather die silent than to bring shame upon his people.

The Vigilantes said to Frank, just before he was executed:

"Tell us if the negro is guilty. We know where he is, and if you say he, too, is guilty, we will give him the same that you are to get."

Frank remained silent. He did ask the Vigilantes to shoot him.

They answered, "No, you were not sentenced to be shot; you were sentenced to be hanged, and that's what we are going to do."

He seemed about to make a full confession, but a nervous Vigilante said something about the soldiers coming to rescue him, and he closed up.

He asked for a box, that he might jump off, and break his neck. He was told that there was no box at hand, and no time to get one.

His last words were:

"God, forgive me!"

Not once did he say that the negro had lied on him; not once did he claim that the other witnesses had sworn falsely; not once did he claim that the trial was unfair and the verdict unjust.

He made one very significant statement which seems to prove that the negro held back some sort part of the truth. He said, "The negro did not tell it all."

Once or twice, he appeared to be on the point of telling what it was the negro left out, but he checked himself.

Strange to say, he slept most of the way, on that long night-ride; his wound had practically healed, and all talk upon the "tortures" he suffered on the road, or at the tree is utterly unfounded.

He was treated just as though the Sheriff and Bailiffs were taking him to the gallows, under the sentence of the courts.

My information as to Frank's confession ("The negro told the story") came to me September 12th, from gentleman who got it from one of the Vigilantes.

The negro did tell the story, and he was corroborated, not only by the testimony of more than forty white witnesses, but by the physical condition of the second floor of the factory, by the physical conditions in the basement, by the physical condition of Mary Phagan's body, and by the physical condition of Leo Frank, on the morning after the crime.

Celebrated crimes have their uncanny fascination, else so many books would not have been written about them. I fear that wicked people interest us more than the good ones do; and I feel certain that most boys would rather read about robbers, highwaymen and pirates, than about Moses, Job, and the other Saints. Give us the biography of a truly virtuous man, like Archbishop Whatley, and we are apt to doze over it; but place in our hands the memoirs of some grand rascal—like Benvenuto Cellini—and we will get wide awake at once.

Now, this Frank case has been made one of the celebrated cases; and, for many years to come, its baleful consequences will be felt. Let us, therefore, try to understand it.

In the August and September numbers of this magazine, the official evidence was discussed and a digest of it published. I will not repeat anything contained in those issues, but will give you a view of the case from altogether another standpoint.

1. The negro's story was corroborated by more than forty white witnesses, in that Frank was proven to have been just the kind of man the negro said he was; in that the elevator was found unlocked, as the negro said it had been left, after the carrying of the corpse to the basement; in that the signs of dragging over the gritty dirt floor came straight and continuous, from the elevator to where the corpse lay; in that there were absolutely no signs of any struggle on any floor except Frank's; in that the girl's face showed she had been dragged on it; in that her drawers showed a rip-up, to the vagina, which had been penetrated but which contained no seminal emission; in that white girls swore to Frank's lewd doings with one of the girls in the factory in the daytime; and in that one white girl swore that Frank had proposed sodomy to her, in his office, on the second day she went to work for him.

A stubborn contest was made by the defense in the effort to show that Frank was not aware of Jim Conley's whereabouts, on the day of the crime, the same being a legal holiday, and there being no apparent cause for Jim's presence at the factory.

If Frank was in touch with the negro that morning, and kept him at the closed-down factory, there would be something to explain. Besides, it would powerfully corroborate Jim.

It so happened that Mrs. Hattie Waites and her husband were returning by rail from Savannah, where he had been attending an Odd Fellow convention. At Jesup they saw the Atlanta paper which told of the arrest of Leo Frank and the supposed complicity of Jim Conley.

On seeing the picture of Frank in the paper, the lady exclaimed, "Why, that's the man I saw in close conversation with a negro, last Saturday morning."

Mrs. Waites had taken Frank to be a friend of hers and had approached him to speak to him, when, on getting close to him and looking into his face, she saw her mistake.

Therefore, when she saw the face in the paper she recognized it, for it was a face not easy to forget.

When the solicitor heard of this piece of evidence, he ran it down, by having Mrs. Waites taken to see both Frank and Conley. She unhesitatingly identified them as the two men she had seen talking together, between 10 and 11 o'clock, on the day of the crime, near Sig Montag's place, where Frank admitted he had gone, at that time.

Three other white witnesses placed the negro in the factory, that morning, sitting at the foot of the stairs, near the front door.

What business had he, loitering there, on that legal holiday?

What did Frank talk to him about, on the street, so near the time of the crime?

Obviously, these questions could not be answered to the satisfaction of the jury; and therefore Frank had to brazen it out that he had not seen the negro that day, at all.

Which would you have believed—the four disinterested white witnesses, or the man on trial for his life?

You would have believed the four white witnesses, two of them honest men—Tillander and Graham—and two of them ladies of unimpeachable characters, Mrs. Arthur White and Mrs. Hattie Waites.

Believing these witnesses, you might have felt constrained to place credit on the explanation of the negro, as to why he came to the factory, that closed down that morning, and remained until Frank got through with him.

There had to be a reason for the negro's giving up his holiday, and staying at the factory. Isn't it so?

Well, then, what was the reason?

Frank gave none; the negro did. The negro said it was to keep a watch out while Frank was with a girl whom he expected to come. Conley did not even know what girl Frank expected.

2. The negro's story was corroborated by the physical condition of the second floor, Frank's office floor.

Sworn to as Mary's, the hair found on the handle of the lathe machine could never be shown to have possibly been the hair of another girl. Those few strands of the dead child's golden crown, literally dragged Leo Frank to inevitable conviction. They had to be accounted for, because they had come upon that projecting crank-handle, after Friday evening and before Monday.

Whose hair? and how came it there at that time?

Nobody could answer. Even the negro did not know what it was that Mary fell against when Frank struck her; but his evidence cleared up the mystery, and without his story, it would still be a mystery.

The blood on the second floor, and the absence of blood anywhere else, corroborated the negro; and the fact that neither Frank nor Mary could be seen by Miss Monteen Stover, when she searched for Frank and waited for him from 12:05 to 12:10, most powerfully supported the negro's story of Mary's previous coming, and of the steps of two persons that he heard walking back to the metal room, where the identified hair of the murdered girl was found, the next time the workman came to put his hand on his lathe machine.

3. The negro's story was corroborated by the physical condition of the basement.

There were no signs of any struggle in it; no blood, no torn-out hair, no unusual appearance on the dirt floor.

There was a trail leading from the elevator shaft to the corpse, showing that she had been dragged from the one place to the other, and her face showed that she had been dragged by the heels.

This indicated the work of one man, and a man not strong enough to lift and carry the body. Conley had done it, but Frank was not strong enough. Therefore, when Frank returned to the factory, that holiday afternoon, and locked himself in, he had to get the girl's body away from the elevator, where he and Conley had left it, and he had to drag it. He wanted to place it as far as possible from the elevator, and in the darkest part of the basement to prevent the night-watch from discovering it.

(I may here state that there was no bank of cinders in the basement, nothing in which the girl could have been smothered; and there were no cinders, or ashes, or sawdust in her mouth, in her nostrils, or in her lungs, as some of the recklessly mendacious writers have alleged.)

4. The negro's story was corroborated by the physical condition of the girl's body.

One leg of her drawers had either been carefully torn all the way up the seam, or a knife had cut it in a straight, even line.

The drawers were stained with her blood. Her uterus was virginal, but her hymen had been ruptured, and violence done to the parts a few minutes before she died, according to Dr. H.F. Harris. The inner walls of the member showed rough use, by finger or tongue, or male organ. But there was no seminal fluid.

"You know I ain't built like other men," was the negro's statement of what Frank said to him, at the time.

Powerfully corroborative, was the affidavit of Miss Nellie Wood that Frank made the same remark to her, in the privacy of his office, when he moved his chair close up to hers, tried to insinuate his hands under clothes, and proposed unnatural connexion.

That the cord had been around Mary Phagan's neck a long time, was proved by the purple-black color of her face, and the deep impression in her flesh.

The strip torn by Frank from her underskirt, and folded under her head to catch the blood, was there to show for itself; and it had served the purpose of keeping the blood off the floor in the metal room. If Jim hadn't let the body fall, no blood would have been found anywhere, except in her hair, and on that cloth!

Her hands were folded across her bosom; so stiffly fixed in position that they did not come apart when she was being dragged sidewise, and partly on her face. Jim's story is that he put them down, easy, on the second floor, when he went to where she was lying on her back, dead.

Reject his statement, and you can't explain the position of those little hands.

(There is a detail here, that has baffled me; The girl had evidently been carrying her handkerchief either in her mesh bag, or in her hand; how came it to be bloody?

Jim nowhere mentions that it was bloody, when he picked it up from the floor in the metal room. But it was found near the body in the basement, and it was bloody; how came it so?

Either Frank, or Conley must have wiped his hands on it.)

5. The negro's story was corroborated by Frank's physical condition, the morning after the murder.

The two officers who went out to his house, not to arrest him, but to invoke his assistance in starting clues to the criminal, found him in a rickety state of nerves, and calling for coffee to drink. They describe him as a man who had been drunk the night before.

They knew nothing on that line, and were not looking for evidences of a debauch, but that is what they describe. "The morning after," was there. So much so that John Black advised Mrs. Frank to give her husband a drink of whiskey.

Now listen: The answer given was that Frank's father-in-law had used it all up during the night.

His father-in-law, Mr. Emil Selig, had had acute indigestion, it was said, and had used all the whiskey in the house that night, on this sudden and always alarming, illness.

I'm not doctor enough to say whether whiskey is the usual remedy for acute indigestion, but I am lawyer enough to see in Selig's sudden use for it on that particular night, a most suspicious corroboration of that cook who swore that Frank got wildly drunk on the same night Selig got his acute indigestion.

Strange to say, Selig went on the stand at the trial of Frank, swore to eating breakfast, as usual; swore to eating dinner, as usual; and never said one word about that night attack of acute indigestion, which had caused him to exhaust the whiskey supply, the night after the crime.

Selig, on Sunday morning, had not only made a full recovery from his alarming illness, but showed no bad effects from the liquor.

It was his son-in-law that looked and acted like the man who had been attacked by indigestion, and who had used up all the whiskey.

As you know, the murder of Mary Phagan was committed on the Southern Memorial day, April 26th, 1913. At that time Leo Frank was entering the 32nd year of his age, and Mary lacked a few days of being fourteen. For sentimental reasons, Nathan Straus, William J. Burns, and the Jewish press generally, have referred to Frank as a "boy;" and Governor Slaton went so far as to say in defense of his virtual pardon of his client, that Frank was "too delicate" to have struck Mary the blow which knocked her down.

This delicate middle-aged Jew weighed 127 pounds, and was so full of vitality that no ordinary amount of venery could satisfy him. His eyes, mouth, chin, nose, ears and neck typed him as a sexual pervert.

His lawyers announced ready for trial, when his case was called in court, and they did not suggest a change of venue. They had had months to prepare; they were intimate with local conditions; and, while their management of themselves, their client and their witnesses, showed the grossest lack of discretion and preparedness, they never at any time moved for a mistrial.

Let me explain to the layman, that a presiding judge will stop a trial, discharge the jury, and set another time for the case to be tried, before another jury, if anything occurs in the court room to prejudice defendant's right to a fair trial.

Had any "mob spirit," any "jungle fury," any "psychic drunk," any "blood lust" manifested itself in the sight or hearing of the jury, it would have been the duty of Frank's lawyers to have put an end to the proceedings, then and there, by moving that a mistrial be declared.

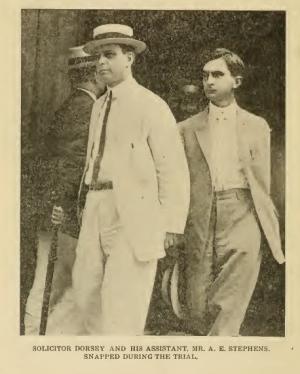

No such motion could be made, because no such facts existed. Frank's lawyers filed a lengthy affidavit, as a part of their extraordinary motion for a new trial, and nowhere do they state that anything occurred in the courtroom, outside those inevitable peals of laughter when one lawyer "chaws" another. I went over this affidavit, of Frank's lawyers, reading it carefully, and was amazed to see that they did not even accuse the court of tolerating misbehavior. These lawyers explicitly say that the jury was not present at all, when the audience in the courtroom applauded a ruling, by Judge Roan, in favor of Solicitor Dorsey.

It seems that Dorsey was hailed, in the streets, with cheers, and these cheers were all that the lawyers of Frank could allege in support of the charge of mob violence, mob spirit, jungle fury, psychic drunk and blood lust.

On the contrary, it was shown by the affidavits of the Sheriff, and all his deputies and the court bailiffs, that no disorders took place during the trial.

Col E.E. Pomeroy, of the Fifth Georgia regiment, swore to the same thing, and so did the newspaper reporters. Every member of the jury made affidavit to the good order maintained, and to their freedom from any disturbance, interruption or attempted influence.

But it is the Sunday American (Mr. Hearst's Atlanta paper), that furnishes the most remarkable evidence as to what was thought, at the time, of the fairness of Frank's trial.

On Sunday, August 24, 1913, "Hearst's Sunday American" published a story of the four weeks' trial, "By an old Police Reporter," which concludes as follows:

"Regardless of all things else, the public is unstinting in its praise and approval of the brilliant young Solicitor General of the Atlanta Circuit, Hugh Dorsey, for the superb manner in which he has handled the State's side of the case.

"It all along has been freely admitted that those two veterans of criminal practice, Luther Rosser and Reuben Arnold, would take ample care of the defendant.

"Two more experienced, able and aggressive attorneys it would impossible to secure in any cause.

"When it was first learned that Rosser and Arnold were to defend Frank, the public realized that the defendant had determined to take no chances. He selected from among the cream of the Georgia bar.

"That the State's interests, quite as sacred as the defendant's, would be looked after so jealously, so adroitly, and so shrewdly in the hands of the youthful Dorsey, however—that was a matter not so immediately settled!

Dorsey an Unknown Quantity.

"Dorsey was known as a ‘bright young chap,' not widely experienced, willing and aggressive enough, but—

"He had been but lately named Solicitor General, and he hadn't been tried out exhaustively.

"Maybe he could measure up to the standard of Rosser and Arnold, but it was a long way to measure up, nevertheless!

"It soon became evident that Dorsey was not to be safely underrated. He could not be sneered down, laughed down, ridiculed down, or smashed down.

"He took a lot of lofty gibing, and was called ‘bud' and ‘son' right along—but every time they pushed him down, he arose again, and generally stronger than ever!

"Time and again he outgeneraled his more experienced opponents.

"He forced them to make Frank's character an issue, despite themselves.

"He got in vital and far-reaching evidence, over protest long and loud.

"Whenever the Solicitor was called upon for an authority, he was right there with the goods. They never once caught him napping. He had prepared himself for the Frank case, in every phase of it.

"The case had not progressed very far before the defense discovered unmistakably that it had in Dorsey a foeman worthy of its most trustworthy and best-tempered steel!

"And the young Solicitor climaxed his long sustained effort with a masterful speech, that will long be remembered in Fulton county!

"In places he literally tore to pieces the efforts of the defense. He overlooked no detail—at times he was crushing in his reply to the arguments of Rosser and Arnold, and never was he commonplace!

Fixed His Fame by Work.

"Whatever the verdict, when Hugh Dorsey sat down, the Solicitor General had fixed his fame and reputation as an able and altogether capable prosecuting attorney—and never again will that reputation be challenged lightly, perhaps!

"Much credit for hard work and intelligent effort will be accorded Frank Hooper, too, for the part he played in the Frank trial. He was at all times the repressed and pains-taking first lieutenant of the Solicitor, and his work, while not so spectacular, formed a very vital part of the whole case made out and argued by the State. He was for fourteen years the Solicitor General of one of the most important South Georgia circuits, and his advice and suggestions to Dorsey were invaluable."

"A noteworthy fact in connection with the Frank trial is that it generally is accepted as having been as fair and square as human forethought and effort could make it.

It may be true that a good deal of the irrelevant and not particularly pertinent crept into it, but one side has been to blame for that quite as much as the other side.

Ruling Cut Both Ways.

The judge's rulings have cut impartially both ways—sometimes favorable to the State, but quite as frequently in favor of the defense.

Even the big charge of degeneracy, which many people hold had no proper place in the present trial, went in without protest from the defense, and cross-examination upon it even was indulged in.

Unlimited time was given both the state and the defense to make out their cases; expense was not considered. This trial has lasted longer than any other in the criminal history of Georgia. Nothing was done or left undone that could give either side the right to complain of unfairness after the conclusion of the hearing.

IT IS DIFFICULT TO CONCEIVE HOW HUMAN MINDS AND HUMAN EFFORTS COULD PROVIDE MORE FOR FAIR PLAY THAN WAS PROVIDED IN THE FRANK CASE.

Mark it! This was published after the evidence was all in, and while Dorsey was closing the argument for the State.

Nobody knew what the verdict would be. But Hearst's Atlanta paper told the world, that it is difficult to conceive how human minds and human efforts could provide more, FOR FAIR PLAY, than was provided in the Frank case.

The trial had been generally regarded "as fair and square, as human forethought and human effort could make it."

So said the Hearst papers on Sunday before the verdict had been rendered.

After the verdict of "Guilty" was Hearst one of the men who bitterly denounced the jury, and the courts? He was.

When the officers told Frank that a girl named Mary Phagan had been found in his basement, he did not make any exclamation of surprise and horror! He took the news as a matter of course. He did not ask anything about the condition of her body, the physical evidences of the crime, or the probable time, place, manner and motive of the act. He did not offer any surmise as to who did it. He expressed no concern whatever. His demeanor was exactly that of a man who knew all about it and who had no questions to ask, after being told of the murder.

Was that the conduct of an innocent employer, whose little employee had been found dead in his house? If Mary Phagan had been a cow that had been choked to death in Frank's enclosure, his conduct could not have been more unfeeling, more stoical.

He did say that he did not know any girl of her name, and couldn't tell, until he consulted his pay-roll whether Mary Phagan had worked for him, or not.

In passing to the toilet daily for a year, he had almost brushed Mary on his way; and four disinterested white witnesses swore that he knew her well, and familiarly called her "Mary."

Not only that, he seemed jealous of J.M. Gantt because of his apparent intimacy with the girl, and he spoke to Gantt about it. An unexplained shortage in the cash account was soon afterwards discovered, and when Gantt denied responsibility, and refused to make it good, Frank discharged him.

So recently had Frank got rid of Gantt, that the man came back to the factory to get two pairs of shoes which he had left there, and this was on the same day that the Jew killed the girl.

To fasten the crime upon some one else, and to hang an innocent man, Leo Frank accused the night-watch in the two notes, describing him twice—which Jim Conley could not have done, for he had never seen the night-watch and did not know he was tall, slim and black. Frank also secreted the true time-slip that was in the clock, the night after the murder, and substituted another, which left one hour of the watchman's time unaccounted for. This hour was to be filled with a supposed return of the watchman to his house, the purpose of the return being to change his shirt. Accordingly, a bloody shirt was found in the watch-man's clothes-barrel! Had not Jim Conley broken down and confessed, it is practically certain that the Burns agency would have hired Ragsdale and Barber to swear that it was the night-watchman whom they heard confess the crime, instead of Jim Conley.

This deliberately planned scheme to lay the crime on the night-watch reveals itself in the notes, in the forged time-slip, in the "planted" shirt, and in Frank's sinister suggestions to the detectives that the night-watch ought to know more about it.

If a black case could be made blacker, this diabolical attempt to hang the innocent negro, while shielding the guilty one, would deepen the darkness of this terrible crime.

During the days of excitement, suspense, eager inquiry, tireless research that followed the crime, Leo Frank never uttered a syllable which would implicate Jim Conley. Yet he was familiar with Conley's crude "hand-write," had seen the notes when they were first found, and saw that in those notes Jim Conley was describing and accusing the night-watch, who had only been three weeks and whom Conley had never seen!

Standing out in the turbid waters of this case are three peaks upon which the Ark of Life would have rested, had the Jew been innocent:

1. He would have explained, and had his parents-in-law to explain, why their daughter, Frank's wife, shunned the imprisoned husband for three whole weeks, after he was committed to jail.

His father-in-law and his mother-in-law both went on the stand to testify to Frank's natural conduct on the Saturday night of the crime, and the Sunday following.

Why didn't they explain the unnatural conduct of their daughter?

The Solicitor could not have gone into this, for it would have been using wife against husband, which our law will not allow. But the defendant could have gone into it fully, to explain an extraordinary fact that was already in evidence.

Why didn't Frank's lawyers call upon the Seligs to tell the jury why their daughter shrank away from her husband for three whole weeks, when he was in jail, accused of rape and murder?

2. When eleven white girls swore to Frank's vicious character, the indignation of an innocent man, would have prompted him to a rigid cross-examination of those witnesses.

The innocent man would have faced those perjured women, and fired at them questions like these:

What did you ever see me do, or attempt to do, that was immoral?

What did you ever hear me say, that was lewd?

Did I ever attempt to mislead you?

If so, where and when?

What did I say, and what did you say?

Did you ever notice any lascivious conduct of mine in the factory?

If so, with whom?

Were you ever in my employ, and did you quit, or were you discharged?

If you voluntarily quit, what was your reason?

If you were discharged, what was the cause?

To whom, before now, have you ever stated that my character was lascivious?

In other words, if these women were perjurers, defendant knew it, and his lawyers should have riddled them on cross-examination.

On the contrary, if they were telling the truth, defendant knew it, and it was better not to make matters worse by cross-examination.

Which course did Frank and his lawyers adopt?

The latter!

3. Beleaguered by false witnesses and suspicious circumstances, the innocent man invites investigation, courts inquiry, offers to explain away what is otherwise inexplicable.

The guilty man fears investigation, and shuns inquiry. It told heavily against Police Lieutenant, Charles Becker, of New York, that he did not go to the witness stand. His seeming fear of cross-examination hurt him badly in public opinion.

But Leo Frank went to the stand, and occupied many, many hours talking to the jury, and then refused to allow the Solicitor to ask him one solitary question!

Our Georgia law gives that privilege to every defendant, and this most lenient of codes gives the jury the right to believe the unsworn, unsifted statement of the defendant in preference to all the sworn and sifted testimony!

Accused by a "low-down, drunken, shiftless negro!"

Accused of indescribable practices in his place of business!

Accused of proposing the obscene thing to a girl on the second day of her employment!

Accused of bringing a most dissolute woman of the town into his office, and acting lower than any beast with her!

Accused of taking Rebecca Carson into the ladies' private room, and shutting himself in there with her alone for 15 to 30 minutes—the girl's mother being a worker on the same floor!

Accused of lusting after Mary Phagan, pushing his attentions on her, laying a trap for her by refusing to send her pittance by her chum.

Accused of giving Jim Conley his instructions the morning of the crime, and causing him to come and be ready to watch the front door, when the doomed child should arrive.

Accused of decoying the little one to the metal room on the pretense of looking to see whether there would be material for her to work with, the next work day!

Accused of shutting the door on this employee of his, and attempting to get her to let him do, with her, what Miss Nellie Woods swore he wanted to do, with herself, and what Dewey Hollis told Judge Roan, to Frank's face, he did do with her!

Accused of resenting the girl's horrified refusal, and of knocking her down, committing the act with her, after she was down, and then, to prevent exposure and punishment, tieing a hemp cord around her throat and choking her to death!

Accused of dragging the dead girl by the heels over the basement floor, until she was lying prone upon her purpled face, in the obscurest nook of that dark room, and of then turning down the gas-jet, until it was no bigger and brighter than a "lightning-bug," so that the night-watch would never see that gruesome figure lying—all rumpled, and bruised, and bloody—away off there by the back door.

Accused of all this, menaced by the coinciding testimony of more than forty white witnesses, encircled by a chain of physical facts which no human power could annihilate, ignore, confuse, or elucidate—compassed around about in this way, and then stand upon the privilege of not allowing a single question to be asked him?

Never in God's world did innocence so act, never!

After the verdict of guilty, the defendant made a motion for a new trial, alleging many errors committed by Judge Roan, and, also, that there was not sufficient evidence to support the verdict.

After a long, careful, conscientious consideration of the motion, Judge Roan overruled it. In doing so he said that he himself did not know whether Frank were guilty, but that the law placed the responsibility for that issue upon the jury. Of course it does. For hundreds of years, juries have been the judges of the facts. Governor Slaton stated the legal principle, in almost the same words, when in 1914, he denied the application for clemency in the Nick Wilburn case. He did the same thing, last year, in the Umphrey and Cantrell cases.

Frank's lawyers took the case to the Supreme Court, where the alleged errors were elaborately argued. The majority Justices held that the evidence was sufficient to support the verdict, and that Judge Roan had not committed any substantial errors of law.

The minority Justices held that Judge Roan had committed one error, to-wit: He had allowed the evidence of Dalton and Conley to establish independent acts of licentiousness on the part of Frank. This evidence, however, was merely cumulative, there being enough unquestioned testimony before the jury to convince them of Frank's vices.

The majority Justices reasoned that the evidence in question was properly admitted, because it tended to prove Frank's character and conduct in the place where the crime was committed; and, therefore, tended to establish the identity of the criminal.

The State's theory being that the murder was incidental to a sexual act, and there being evidence to support this theory, it was competent to introduce testimony to prove that it was Frank who used the factory for sexual acts.

The minority Justices never said that the evidence was not sufficient to support the verdict.

After the Supreme Court decided the case, the trial recommenced, in the newspapers. According to all precedent and practice, the question of Frank's guilt had been settled. His guilt had been judicially ascertained. The Law had done its do. The Law said "It is finished."

Not so the newspapers. The Atlanta Journal (whose managing editor is a Jew), published an inflammatory editorial, demanding that the decision of the Supreme Court be defied!

The Journal announced a new doctrine as to the responsibilities of a State for the administration of justice. It said:

Responsibility for the enforcement of the law and the punishment of crime rests largely but not exclusively upon the courts. The press also has its share of responsibility, and it seems to the Journal that the time has come for the press to speak. The Journal will do so now even though every other newspaper in Georgia remains silent.

Here was a novelty. Never before had any Southern man announced that a portion of the judicial power is vested in the publishers of newspapers.

The Constitution of Georgia puts the responsibility on judges and juries; but the Journal declared that "a share" of this responsibility is on the press.

What share? Half, or less than half? Where is the "share" to be allotted, when, and by whom?

Did the press tote its "share" in the year 1914, when four Gentiles were hanged for murdering men? What did the Atlanta Journal do with its "share," when Lep Myers got off at manslaughter, after going to a Gentile woman's room, in Macon, and atrociously shooting her to death.

The Journal further said:

The courts have their greatest responsibilities and their arduous duties to perform, and be it said to their everlasting credit, they discharge those duties to the best of human ability. But even juries are sometimes swayed by environment and the judicial ermine is not infallible. Infallibility is an attribute of omnipotence.

The Journal further said:

"Leo Frank has not had a fair trial. He has not been fairly convicted and his death without a fair trial and legal conviction will amount to judicial murder."

The Journal further said:

"Unless the courts interfere we are going to murder an innocent man by refusing to give him an impartial trial."

The Jew Editor of the Atlanta Journal further said: