by Thomas E. Watson, Watson's Magazine, Volume 20 Number 5, March 1915

ON THE 23rd page of Puck, for the week ending January 16, 1915, there is, in the smallest possible type, in the smallest possible space, at the bottom of the page, the notice of ownership, required by law.

Mankind are informed that Puck is published by a corporation of the same name, Nathan Strauss, Jr., being President, and H. Grant Strauss being Secretary and Treasurer. You are authorized, therefore, to give credit to the Strauss family for the unparalleled campaign of falsehood and defamation which Puck has persistently waged against the State of Georgia, her people, and her courts. In as much as the Strauss family once lived in Georgia, and are loudly professing their ardent devotion to the State of their birth, you may feel especially interested in Puck.

Looking over the pages of this Strauss publication, I find a characteristic thing: on page 22, there is an illustrated advertisement of "Sunny Brook Whiskey" which is recommended as "a delightful beverage, and a wholesome tonic." To give force to the words of testimonial, there is a picture of an ideally good-looking man, and this smiling Apollo is pointing his index finger at a large bottle of the delightful Sunny Brook fire-water.

On the next page, is a strikingly boxed advertisement of "The Keely Cure Treatment," with references to such nationally known stew-it-out resorts as Hot Springs, Arkansas; Jacksonville, Florida; and Atlanta, Georgia. The advertisement states that the Keely Cure is "John Barleycorn's Master," and that during the last thirty-five years half-a-million victims of the drink appetite have been cured.

Therefore, the Strauss magazine is open to contributions from both sides. Those who don't want the Keely Cure, are told where to get the liquor; while those who have had too much of the liquor, are told where to get the Keely Cure. In either event, the Strauss family continue to do business, and to add diligent shekels to the family pile.

Puck is one of those magazines which indulges in fun, for the entertainment of the human race. You can nearly always tell what sort of a man it is, by the jokes he carries around with him. In parallel column to the ad. of the Sunny Brook Whiskey, Puck places a delicate little bit of humor, like this:

"We stand behind the goods we sell!"

The silver-throated salesman said.

"No! No!" cried pretty, blushing Nell,

"You see, I want to buy a bed!"

Another bit of refined fun, which is so good that the Strauss family went to the expense of a quarter-page cartoon, represents a portly evangelical bishop, seated in the elegant room of a young mother, who is at the tea-table, close by, pouring "the beverage which cheers but not inebriates." Her little boy sits on the bishop's knee, and the kindly gentleman, with one hand on the lad's plump limb, exclaims, "My! My! What sturdy little legs!" and the boy answers, "O, you ought to see mother's!" and the mother is in arm's length of the bishop!

The tone of Puck, and its sense of responsibility to its readers, when discussing matters of the gravest public concern, is shown by its treatment of the profoundly serious and important subject of Prohibition. I quote what Puck says, not to exhibit Richmond Pearson Hobson, or the pros and cons of Congressional legislation on that question, but to exhibit the levity and dishonesty of Puck:

Congress was treated to an excellent vaudeville a few days ago as part of the prohibition propaganda engineered by that earnest young white-ribboner, Richard Pearson Hobson. From all press reports of the session, it must have been an inspiring sight.

Mr. Hobson had placed in the "well" of the House—the big space in front of the clerk's desk—twenty large lettered placards pointing out the alleged evils of the "liquor curse." Some of those placards were: "Alcoholic Dogs Had More Feeble and Defective Puppies," "Destructive Effect of Alcohol on Guinea Pigs," etc.—New York Tribune.

Puck has long pointed out the terrible effects of alcoholic indulgence among our canine friends. It feels, with Mr. Hobson, a heartfelt pity at the picture of a tipsy terrier going home to a boneless doghouse and a hungry litter. But Mr. Hobson's flapdoodle did not stop here. He rants:

"The national liquor trust in America opened four different headquarters in Alabama and conducted the major part of the great campaign against me, with their one hundred stenographers and eight hundred men on the salaried payroll. I found out also that Wall Street—and I am not guessing—raised a fund which was sent there to defeat me."—New York Tribune.

Poor old Wall Street! No sooner is it out of the doldrums of an enforced vacation than it is dragged into action to lead that peerless force of "one hundred stenographers and eight hundred salaried men" against Mr. Hobson. It is a heart-rending picture, this spectacle of impoverished financiers passing 'round the hat to collect a fund to be used in behalf of the Demon Rum. Wall Street reeks with whiskey—if we believed the oratory of Prohibition's Alabama advocate.

But, to continue:

That whiskey is killing daily more men in the United States than the war is taking away in Europe, was one of the statements emphasized by Mr. Hobson.—New York Tribune.

Is it to be wondered that the cause of Prohibition, championed with such rubbish as this, met with a decisive and well-deserved defeat?

The prominent feature of this number of Puck, is another full-page cartoon, by Hy Mayer, representing Leo Frank, this time, as an innocent prisoner barred from his freedom by the symbolic columns of "Wisdom, Justice, and Moderation," as they appear on Georgia's coat of arms. The Strauss accusation is, that the State has falsified her own motto, and converted her temple into a Bastille, through whose bars the innocent Frank is gazing outward for the liberty of which he has been so unlawfully deprived.

A paragraph on another page runs thus:

IN SAFE HANDS AT LAST.

Perhaps the Georgia mob that hooted its way to fame outside the court-room where Frank was being tried for his life will now pack up its carpet-bags and journey to Washington.

The Supreme Court of the United States would doubtless be tremendously overawed by a demonstration of mob violence on the part of an Atlanta delegation.

What are people to do, when mercenary detectives, and newspapers, and Hessians of the pen, hire themselves to push a propaganda of libel and race prejudice, in the determined effort to hide the evidence of Frank's guilt, nullify the calm decisions of our highest court, and substitute the clamor of Big Money for the stern, impartial mandate of the Law?

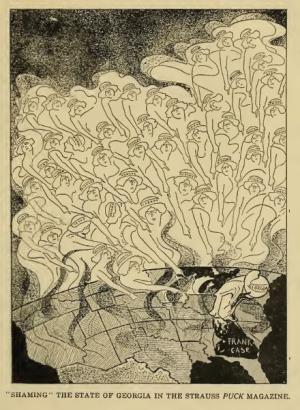

In this same issue of the Strauss magazine, is another cartoon, by M. De Zayas, labeled, "ALONE IN HER SHAME!" The subject of odium is the State of Georgia, and she is pictured as being pointed at by the scornful fingers of all the other States.

If this kind of thing could work a mercurial public into hysteria, or hypnotize a governor into blue funk, what rich criminal would ever go to the scaffold? If Big Money can hire Hessians enough to fight Frank's way out of the consequences of his awful crime, what is it that Big Money cannot do?

In the same Strauss magazine for January 30th, there is a still more insulting and defamatory cartoon. We reproduce it, for the information of our readers. It pictures the State of Georgia as a masked ruffian, with a coil of rope in his hand, trying to seize Leo Frank, and lynch him, without a legal trial. The witnesses to the scene are Uncle Sam, and a touring-car full of the other States in the Union! A guide, with a megaphone, is proclaiming the infamy of Georgia.

In all of the months during which William J. Burns has been working these agencies to create sentiment in favor of Frank, not a page of the essential sworn testimony has been given to the public. On the contrary, the wildest rumors, and the most craftily devised falsehoods, have been put into circulation, in the effort to get a favorable verdict from unthinking editors and readers who are slow to suspect that there is a systematic campaign of willful lies.

Excuse me for speaking plainly, the time has come for it.

Let us begin with Collier's. This is the weekly paper which has sold books in so many peculiar ways, and made a nation-wide campaign against patent medicines—and then stopped quite suddenly.

It is the paper which editorially accused the white women of the United States of squealing on their negro paramours, and thereby causing them to be lynched—to avoid scandal!

The exact language of Collier's was—

It is well known that many identifications are mere hysteria, often for crimes that were never committed, and many charges and identifications are founded on something worse than hysterical invention; they are the easiest escape from scandal. Now these are not the things to say, no doubt. They altogether lack chivalry and the aristocratic virtues. But perhaps it is time to put justice and truth above "honor," whatever that may be.

Thus spoke Collier's editorially in October 1908.

Is Collier's the kind of publication which you would select for the championship of Truth?

Is Collier's the weekly that would go to great expense in the Frank case, for the holy sake of Justice?

C.P. Connolly had been with William J. Burns in the McNamara cases, and Burns took up Connolly in the Frank case, to blow some bugles through the Baltimore Sun, the daily paper of the worthy Abells. After the Abells got through with Connolly, Collier's picked him up, and translated him to Atlanta. What did he do there? With whom did he talk? How did he try to get at the facts of the Frank case?

He did not go over the record, with the Solicitor who was familiar with it, and who proffered his services to Connolly for that very purpose!

If Connolly came for the truth, why did he not listen to both sides? Why did he not read the record? Or if he read it, why did he so grossly misrepresent it?

Let us examine a few of Connolly's statements—statements which being accepted as true, have poisoned the minds of honest people throughout the Union, just as they were meant to do!

Connolly says—"Leo M. Frank is a young man of whose intellectual attainments any community might well be proud. Atlanta has been combed to find something against his moral character….but without success."

There you have a flat, positive assertion that the city of Atlanta was diligently searched for witnesses who would testify against Frank's moral character, and that none could be found.

What will be your amazement and indignation, when I tell you that numerous white girls and white women went upon the witness stand, and swore against Frank's moral character?

One after another, those white accusers, braved the public ordeal and testified that Frank was lewd, lascivious, immoral!

Frank's lawyers sat there in silence, not daring to ask those witnesses for the details upon which they based their terrible testimony.

Why did Frank's lawyers allow that fearful evidence to have its full effect upon the jury, without asking those white women what it was they knew on Frank?

Suppose you had been accused in this case, and those same witnesses had testified against your character, would you have been afraid to cross-examine them?

Only a man who shrank from what those women could tell on him, would have let them go, without a single word! The State could not ask them for specific facts. The defendant alone had the legal right to ask for those—and the defense was afraid to do it.

Among those white witnesses were, Miss Marie Karst, Miss Nellie Pettis, Miss Maggie Griffin, Miss Carrie Smith, Mrs. C.D. Donegan, Miss Myrtie Cato, Mrs. Estelle Winkle, Mrs. M.E. Wallace, Mrs. H.R. Johnson, Miss Mary Davis.

Another white girl who did not know enough of Frank's general character for lasciviousness, to swear against it, was offered by the State to prove that she went to work in Frank's factory, and that Frank made an indecent proposal to her, on the second day!

Frank's lawyers objected to the evidence, and Judge L.S. Roan ruled it out. But if Connolly was eagerly bent on finding the truth as to Frank's character, he would certainly have heard of Miss Nellie Wood, who doubtless can tell Connolly at any time the exact language that Frank used in his effort to corrupt her.

When you pause to consider that here were many white witnesses, none of whom could be impeached, who took a solemn oath in open court, and swore to Frank's immoral character—standing ready to bear the brunt of the cross-examination of the crack lawyer of the Atlanta bar—what do you think of Connolly, when he states that no such witnesses could be found? And what do you think of Burns, who pulled off the jackass stunt of afterwards offering "a reward" for any such witnesses?

With reference to his said offer of the $5,000 reward, this impostor, Burns, said on Feb. 3, in the Kansas City Star, which is (disinterestedly, no doubt) giving so much space to the campaign of slander against the people and courts of Georgia:

"Let me tell you this—no man has a more remarkable past than Frank. I investigated every act of his life prior to the accusation against him. There was not a scratch on it. Then I offered a reward of $5,000 to anyone who could prove the slightest immorality against him. No one, not even the Atlanta police, have attempted to claim it."

Instead of his flamboyant and empty offer of $5,000, why didn't Burns quietly take Rev. John E. White, or some other respectable witness, with him, and visit the white ladies who had already publicly testified to Frank's lewd character?

Those white ladies were right there in Atlanta, while that noisy ass, Burns, was braying to the universe. The record showed him their names. If he wanted to know WHAT THEY COULD TELL ON FRANK, why didn't he go and ask them?

He knew very well that nobody would claim his reward, for he knew that there wasn't anybody who was fool enough to believe they could ever see the color of his money.

If he wants to learn the truth about Frank's double life, he can go to those ladies now!

WHY DOESN'T HE DO IT? He can save his imaginary $5,000, and ascertain the truth, at the same time.

The mendacious scoundrel was quick enough to hunt up Miss Monteen Stover, and use his utmost efforts to scare her into changing her evidence. He went so far as to entrap her, in Samuel Boornstein's office, where the attempt was made to hold her by force.

Other girl witnesses, in the case were subjected to persecution and threats, by these infamous Burns detectives, who wanted to change their evidence, as they did change the fearful evidence of Frank's negro cook.

Why was Burns afraid to ask Mrs. Johnson, or Mrs. Winkle, or Mrs. Donegan what it was, that caused them to swear that Leo Frank is a libertine? Miserable faker! He didn't want the truth.

Do William J. Burns and Luther Rosser mean to say that all these respectable white girls and ladies who swore to Frank's immoral character, perjured themselves? If so, what motive did they have? And if Rosser was satisfied those ladies were swearing falsely, why didn't he cross-examine them? Why was he afraid to ask them a single question?

Your common sense tells you why. Rosser feared what would COME OUT!

Another statement made by Connolly is, that the face of the dead girl "was pitted and seamed with indentations and scratches from the cinders, a bank of which stretched along the cellar for a hundred feet or more. There had evidently been a struggle."

Again, Connolly says—

There were cinders and sawdust in the girl's nose and mouth, drawn in, in the act of breathing, and under her finger nails. Her face had been rubbed before death into these cinders, evidently in the attempt to smother her cries.

Here the purpose of Connolly was, to make it appear that Mary Phagan had been killed in the basement, after a struggle, during which her mouth had been held down in the cinders, to stifle her screams!

In that event, of course, her tongue, her mouth, her throat, and perhaps her lungs would have shown saw-dust, and cinders.

There is absolutely no evidence in the record to support any such theory.

There was absolutely no evidence of any long "bank of cinders," in the basement. There was, in fact, no such bank of cinders!

(See evidence of Defendant's witness, I.U. Kauffman, pages 148, 149, 150. Also, evidence of Dobbs, Starnes, Barrett, &c.)

The evidence of all the witnesses is, that the girl's tongue protruded from her mouth, and that the heavy twine cord had cut into the tender flesh of her neck, and that the blood-settlings showed the stopped circulation—manifest not only in her purple-black face, but under the blue finger nails.

There was no evidence whatever of cinders, ashes, or saw-dust in her mouth, in her throat, or in her lungs.

There was not a scintilla of evidence that she had met her death in the basement!

(See evidence of Dobbs, Starnes and Barrett.)

The sworn testimony in the record is, that, although the girl's face was dirty from having been dragged by the heels through the coal-dust and grime, natural to the basement where the furnace was, the negro who first saw her that night, by the glimmer of a smoky lantern, telephoned to the police that it was a white girl. The officers, Anderson and Starnes, so testified!

Sergeant Dobbs swore that the body seemed to have been dragged by the heels, over the dirt and coal-dust, and that the trail led back from the corpse to the elevator. His exact words are, "It began immediately in front of the elevator, at the bottom of the (elevator) shaft."

The word, "It," refers to the trail of the dragged body; and the witness swore that the thought the condition of the girl's face "had been made from the dragging."

There was the unmistakable sign of the dragged body, as legible as the track of a foot on the soft ground; and the weight of the head and the friction, in dragging and bumping, would naturally cause soilure and abrasions. (The distance was 136 feet.)

W.E. Thomson whose booklet of 32 pages has been generously scattered "from the Potomac to the Rio Grande"—in the evident effort to reach all of his blood-relations who, as he tells us, are dissolutely distributed over the entire region between these two watercourses—W.E. Thomson says, on page 18 of his rambling, incoherent pamphlet.—

"There is not a shadow of doubt that she was murdered in this basement, on this dirty floor. The back door had been forced open by drawing the staple. This door opened out on an alley back of the building. There is every reason for believing that the murderer went out that door."

Thomson argues that Jim Conley did the work.

But why did Jim Conley have to draw the staple, and leave the building by that door? Conley had the run of the building, was in it that fatal Saturday, was there when the white ladies and girls left, and was gone, in the usual way, when Newt Lee came on duty for the evening, as night watch.

The basement door was not then open. But the crime had already been committed, and the dead body lay there in the gloom. Whose interest would it serve to afterwards draw the staple, and give the door an appearance of having been forced?

When William J. Burns came to Atlanta, last Spring, and began his campaign of thunder and earthquake, he deafeningly shouted to the public at every step he took. His very first whoop was, that a careful examination of the facts in the case showed that the crime had been committed by "a degenerate of the lowest type." Burns roared the statement, that the guilty man had never been suspected, and was still "at large."

Burns yelled that this unsuspected criminal of the lowest type was hiding out, somewhere nearer to the North pole than Atlanta; and, with an ear-splitting noise, Burns set out to find that man. Burns said he was "utterly confident" he would find this man—who was expected to wait calmly, until Burns could nab him.

As everybody who read the papers last summer knows, that was precisely the theory upon which Burns started to work. He went on a wild-goose chase, into the Northern States, and was gone for months, working the Frank case. Working it how? Hunting for what?

He didn't have to go North to find evidence against Jim Conley. Every bit of evidence against Jim was right there, in Atlanta.

Burns has never produced a single witness from the North. Not a scrap of testimony resulted from all his months of labor in the North! What was he doing there?

From day to day, and week to week, he put out interviews in which he declared he was making "the most gratifying progress."

"Progress," at what? "Gratifying," how?

My own idea was, that Burns spent his time chasing around after opulent Hebrews; and that his gratifying progress consisted of relieving the prosperous Children of Israel of their superfluity of ducats. It takes money to stimulate the activities of such a peculiar concern as the Burns Detective Agency.

In one of his many interviews, published in the papers of Cain and Abel, this great detective, Burns, said, "The private detective is one of the most dangerous criminals that we have to contend with."

I considered that the superbest piece of cool effrontery that a Gentile ever uttered, and a Jew ever printed. You couldn't beat it, if you sat up of nights, and drank inspiration from the nectar Jupiter sips.

Week after week, Burns pursued the pleasures of the chase, up North, presumably bringing down many a fat Hebrew. He not only got a magnificent "bag" of rich Jews, but, with the unholy appetite of an Egyptian turning the tables on the Chosen People, he spoiled them to such an extent that it was a "battue."

Having bled these opulent Hebrews of the North until they were pale about the gills, and mangled in their bankbooks, William J. came roaring back Southward, oozing newspaper interviews at every stop of the cars. Burns said he had his "Report" about ready. That Report was going to create a seismitic upheaval. That Report would astound all right-thinking bipeds, and demonstrate what a set of imbeciles were the Atlanta police, the Atlanta detectives, the Pinkerton detectives, the Solicitor-General, the Jury, the Supreme Court, and those prejudiced mortals who had believed Leo Frank to be the murderer of Mary Phagan.

Naturally, the public held its breath, as it waited for the publication of this much-advertised Report. At last, it came, and what was it? To the utter amazement of everybody, it consisted of an argument by Burns on the facts that were already of record. He did not offer a shred of new evidence.

His only attempt at new testimony was the bought affidavit of the Rev. C.B. Ragsdale, who swore that he overheard Conley tell another negro that he had killed a girl at the National Pencil Factory.

So, after all his work in the North, and after all his brag about what he would show in his Report, Burns' bluff came to the pitiful show down of a bribed witness who was paid to put the crime on the negro.

As Burns said, "the private detective is the most dangerous criminal we have to contend with." "We" have so found.

Commenting upon the Connolly articles, the Houston, Texas, Chronicle says, editorially:

Collier's Weekly has espoused Frank's cause in its usual intense way, and has put the work of analyzing the facts into the hands of a man who does not mince words; and, while one may not be willing to agree with all of its contentions, there is one point on which it hits the bullseye—that of the speech of the solicitor general, or prosecuting attorney.

In what manner had Collier's hit the bull's eye?

According to Collier's, the speech was "venomously partisan," and the wish is editorially expressed that all lawyers in the United States could read it and let that paper know what they think of it. So presumably it was stenographically reported, and it may safely be assumed that Collier's quotes correctly. It says the Reuf case, the Rosenthal murder and other crimes in which Jews played a part were dragged into the argument.

Elevating himself to the pinnacle of moral rectitude, the editor of the Chronicle says—

In England, where trials are conducted more nearly along proper lines than they are anywhere else in the world, a crown's counsel who would make a denunciatory or emotional appeal to a jury would be adjudged in contempt.

With such a speech, and a crowd which had already prejudged the case filling the court house, a fair trial in the meaning of the constitution and the law was impossible.

In England it would have been different, says the Chronicle.

Yes, it would. In England, Leo Frank would have long since gone the way of Dr. Crippin, and suffered for his terrible crime.

But was Dorsey's speech such a venomous tirade? Was he in contempt of court in his allusions to Reuf and Hummel and Rosenthal? Did Dorsey bring the race issue into the case?

Solicitor General Hugh M. Dorsey's speech was stenographically reported. It makes a booklet of 146 pages. On pages 2, 3, and 4, Mr. Dorsey deals with the race issue and deplores the fact that the "defense first mentioned race."

Mr. Dorsey says, "Not a word emanated from this side, not a word indicating any feeling against…..any human being, black or white, Jew or Gentile.

"But, ah! the first time it was ever brought into this case,—and it was brought in for a purpose, and I have never seen two men manifest more delight or exultation than Messrs, Rosser and Arnold, when they put the question to George Kendley at the eleventh hour.

"A thing which they had expected us to do, and which the State did not do, because we didn't feel it and it wasn't in this case.

"I will never forget how they seized it, seized with avidity the suggestion, and you know how they have harped on it ever since.

"Now, mark you, they are the ones that mentioned it, not us; the word never escaped our mouth."

There sat Frank's lawyers, two of the most aggressive fighters, men who rose to their feet, again and again, during the course of Dorsey's speech, to deny his statements, and interject their own, but they did not utter a word of denial when he charged them to their teeth, in open court, with bringing into the case the evidence that Frank is a Jew. Nor did they challenge his statement that they had "laid for" him to do it, and had done it themselves when they saw that he did not mean to give them that string to harp on.

Having made his explanation of how the fact of Frank being a Jew got into the case, Dorsey paid this glowing tribute to the great race from which this degenerate and pervert sprung:

"I say to you here and now, that the race from which that man comes is as good as our race. His ancestors were civilized when ours were cutting each other up and eating human flesh; his race is just as good as ours,—just so good, but no better. I honor the race that has produced D'Israeli,—the greatest Prime Minister that England has ever produced. I honor the race that produced Judah P. Benjamin,—as great a lawyer as ever lived in America or England, because he lived in both places and won renown in both places. I honor the Strauss brothers—Oscar, the diplomat, and the man who went down with his wife by his side on the Titanic. I roomed with one of his race at college; one of his race is my partner. I served with old man Joe Hirsch on the Board of Trustees of the Grady Hospital. I know Rabbi Marx but to honor him, and I know Doctor Sonn, of the Hebrew Orphan's Home, and I have listened to him with pleasure and pride.

"But, on the other hand, when Becker wished to put to death his bitter enemy, it was men of Frank's race he selected. Abe Hummel, the lawyer, who went to the penitentiary in New York, and Abe Reuf, who went to the penitentiary in San Francisco, Schwartz, the man accused of stabbing a girl in New York, who committed suicide, and others that I could mention, show that this great people are amendable to the same laws as you and I and the black race. They rise to heights sublime, but they sink to the depths of degradation."

After Rosser and Arnold had dragged the Jewish name into the case, could Dorsey have handled it more creditably to himself, and to those Jews who believe, with Moses, Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, that crime must be punished?

Read again what Dorsey actually said as stenographically reported, and remember that Connolly pretended to have read it before he wrote his articles, and then sift your mind and see how much respect you have for a writer who tries to deceive the public in that unscrupulous manner.

C.P. Connolly makes two statements about the law of Georgia.

On Dec. 14, 1915, he stated in Collier's that, "By a constitutional amendment, adopted in 1906, the Supreme Court of Georgia cannot reverse a case on other than errors of law."

This remarkable statement he varies somewhat, in his article published Dec. 19, 1915.

Under a constitutional amendment adopted in 1906, the Supreme Court of Georgia is not allowed to reverse any capital case where no error of law has been committed in the trial, no matter how weak the evidence may be, and cannot investigate or pass upon the question of guilt or innocence.

Since the days of Magna Charta, it may be doubted whether any State, set up under English principles, could legally deprive reviewing courts of the right to annul a verdict which has no evidence to support it. In such a case, the question of evidence would become a question of law. Without due process of law, no citizen can be robbed of life, liberty, or property; and, while it is the province of the jury to say what has been proved, on issues of disputed facts, it is for the court to decide whether the record discloses jurisdictional facts.

It necessarily follows that, if a record showed that no crime had been committed, or, if committed, the evidence failed to connect defendant with it, the verdict would have to be set aside, as a matter of law.

The constitutional amendment of 1906, to which Connolly refers, had for its main purpose the creation of a Court of Appeals, as an auxiliary and a relief to the Supreme Court. In doing this, the legislature had to divide appealed cases between the two courts. The new law provided that the Supreme Court should review and decide those civil cases which went up from the Superior Courts, and from the courts of ordinary, (our chancery courts) and "all cases of conviction of a capital felony."

To the Court of Appeals, was assigned those cases going up from city courts, and all convictions in criminal cases less than a capital felony.

The Supreme Court of Georgia in every open case of motion-for-new-trial, is now constantly passing upon the sufficiency of the evidence to support the verdict; and the Court passed upon that very question, in Frank's first motion for new trial.

I cannot imagine anything that would cause a more universal wave of protest, than an effort to emasculate our Supreme Court, by robbing it of the time-honored authority to review all the evidence in contested cases; and to decide, in the calm atmosphere of the consulting room,—remote from personalities, passions, and the dust of forensic battle—whether the evidence set out in the record is sufficient to support the verdict.

If Connolly's idea of the change made in 1906 were correct, it would lead to the preposterous proposition, that the Supreme Court might have before it a case of a man condemned to death for rape, when the evidence showed that there had been no penetration. The Court would have to let the man die, because the judge below had committed no error of law! Would it not be the greatest of errors of law, to allow a citizen to be hanged, when there is no proof of a crime? Would it be "due process of law," to kill a man, under legal forms, without evidence of his guilt?

Those men who alleged that Connolly is a lawyer, also allege that Burns is a detective. Both statements cut a large, and weird figure, in the realm of cheap, ephemeral fiction. If being a lawyer were a capital offense, and Connolly, were arraigned for the crime, the jury would not only acquit him without leaving the box, but would find a unanimous verdict of "malicious prosecution."

If being a detective were virulent, confluent small-pox, the wildest advocate of compulsory vaccination would never pester Burns. It is as much as Burns can do, to find an umbrella in a hall hat-rack.

A prodigious noise has been made over the alleged statement of Judge L.S. Roan, who presided at Frank's trial, that he did not know whether Frank was guilty or innocent. All of that talk is mere bosh. What Judge Roan said was exactly what the law contemplates that he shall say! The law of Georgia, constitutes the trial judge an impartial arbiter, whose duty it is to pass on to the jury, in a legal manner, the evidence upon which the jury are to act as judges.

They are not only the judges of the evidence, but the sole judges of it. The slightest expression of an opinion from the bench, as to what has or has not been proven, works a forfeiture of the entire proceeding.

In no other way, can a defendant be tried constitutionally, by his peers, than by clothing the twelve jurors whom he, in part, selects as his peers, with full power to adjudge the facts.

(I am confident that it is the intention of the law to also make these peers of the accused the full judges of the law, to exactly the same extent that they are absolute judges of the facts; but that is a question not germane to the Frank case.)

Now, if Connolly and Collier's had taken the pains to examine our law, they would have realized that the legal intendment of Judge Roan's declaration was no more than this:

"It is not for me to say whether this man is innocent or guilty. That is for the jury. They have said that he is guilty, and I find that the evidence sustains the verdict. Therefore, I refuse to grant the motion for new trial."

In ninety-nine cases out of a hundred, our judges utter some such words as those, in charging the jury, and in passing upon motions for new trial.

I will say further, that a lack of definite opinion as to the guilt or innocence of the defendant at the bar, is an ideal state of mind for the presiding judge.

We are all so human, that if the judge feels certain of the guilt, or innocence of the accused, he will "leg" for one side or the other.

So well is this understood, that the trial judge almost invariably takes pains to say to the jury—

"Gentlemen, the court does not mean to say, or to intimate what has, or has not, been proven. That is peculiarly your province. It is for you to say, under the law as I have given it to you, whether the evidence establishes the defendant's guilt beyond a reasonable doubt, &c."

There isn't a lawyer in Georgia who hasn't heard that kind of thing, times without number.

If Judge L. S. Roan did, indeed, keep his mind so far above the jury-function in this case, that he did not form an opinion, either way, he maintained that ideal neutrality and impartiality which the Law expects of the perfect judge.

The St. Louis Post-Dispatch is another paper that has taken jurisdiction of the Frank case. It employs another famous detective for the defense, a New York person, named George Dougherty. Every detective who favors Frank is a famous detective, a scholar, a gentleman, a deep thinker and a model citizen—just as Frank is.

Those detectives and police officers who testify the other way, are bad men, the scum of the earth, crooks, rapscallions, liars, and pole-cats.

The famous detective, George Dougherty, appears to have studied the case hurriedly. He says—

And the office in which Frank was charged with having committed immoral attacks was in direct line of possible observation from several people already in the building, whose approach Conley would have known nothing of.

George D. is mistaken. Frank and the other man took the women to a place where they were not "in direct line of possible observation," &c.

The famous detective again says—

Another point: Conley's statement is that Frank knew in advance that Mary Phagan was to visit the factory that day for the purpose of getting her pay. There is no reasonable cause for believing this to have been true; no other employee went there that day to be paid. If Frank did not know that Mary Phagan was to be there, Conley's entire story falls. And, as a matter of fact, there seems to be more reason to believe that he did not, than there is to believe that he did.

Now, what will you think of this famous detective, when I tell you that page 26 of the official court record of this case shows, that Monteen Stover swore she went there to get the wages due her, and was at the office of Frank at the fatal half-hour during which he cannot give an account of himself?

George Dougherty does not even know that Frank, in his statement to the jury, stated that Miss Mattie Smith came for her pay envelope, that Saturday morning, and also for the wages due her sister-in-law; and that he gave to the fathers of two boys the pay envelopes for their sons.

This makes five other employees—two in person, and three by proxy—who were there for the wages due them, on the identical day when Mary Phagan went for her pay, and disappeared—the very day when Dougherty asserts, "no other employee went there that day to be paid!"

(See Frank's statement, page 179.)

Is it any marvel that the public has been bamboozled, and the State of Georgia made the object of condemnation, when famous detectives write such absurdities, and respectable papers publish them?

The State of Georgia has no press agent, no publicity bureau, no regiment of famous detectives, no brigade of journalistic Hessians. The State can only maintain an attitude of dignified endurance, while this mercenary, made-to-order hurricane of fable, misrepresentation and abuse passes over her head.

All she asks of an intelligent, fair-minded public is, to judge her by the official record, as agreed on by the attorneys for both sides. All that she expects from outsiders is, the reasonable presumption that she is not worse than other States, not worse than Missouri which tried the Boodlers of St. Louis, not worse than California which tried the grafters and the dynamiters; not worse than Virginia, which tried and executed McCue, Beattie and Cluverius, on less evidence than there is against Frank.

The New York World, owned by the Pulitzers, said in its report of the case:

May 24—On evidence of Conley, Frank was indicted for murder.

July 28—Trial of Frank began.

Aug. 24—Conley testified Frank entrapped the girl in his office, beat her unconscious, then strangled her.

Aug. 25—Jury found Frank guilty of murder, first degree.

"On evidence of Conley," Frank was indicted and convicted, according to the Pulitzers. Of course, the general public does not know that Frank could not have been convicted upon the evidence of Conley, a confessed accomplice. The general public—which includes such lawyers as Connolly—cannot be supposed to know that the law does not allow any defendant to be convicted upon the evidence of his accomplice.

In the St. Louis Post-Dispatch (which I believe is also a Pulitzer paper) there are two recent letters by Wm. Preston Hill, M.D. Ph.D., in which the State of Georgia is violently arraigned.

Wm. Preston Hill, M.D. Ph.D., starts out by stating that "anybody who has carefully read the proceedings in the murder trial of Leo Frank must be convinced…the whole trial was a disgraceful display of prejudice and fanatical unfairness….This whole proceeding is a disgrace to the State of Georgia, and will bring on her the just contempt of the whole civilized world.

"Everywhere thoughtful men will judge Georgia to be filled with semi-barbarous fanatical people of low mentality, and strong, ill-controlled passions, a race to be avoided by anybody who cares for liberty, order or justice."

Then to show what a thoughtful man is Wm. Preston Hill, M.D. Ph.D., and how carefully he has read the record in the case, he proceeds to state that "Frank was convicted on the unsupported evidence of a dissolute negro of bad character" who was contradicted in 22 different instances!

Then Wm. Preston Hill, M.D. Ph.D., gives himself away by advising people to study the case—how?

By an examination of the record that went up to the Supreme Court?

Oh no! Study it by the paid columns of C.P. Connolly, who got his ideas of the case from the rascally and mendacious poseur, William J. Burns.

In the Chicago Sunday Tribune of December 27, 1914, appears a full page article beginning, "Will the State of Georgia send an innocent man to the gallows?"

The writer of the article is Burton Rascoe. The entire article proceeds upon the idea that poor little Mary Phagan was a lewd girl; that she had been immorally intimate with two employees of the factory; that Jim Conley, drunk and hard-up, wanted her pay envelope; that he seized her, to rob her, and that he heard some one calling him, and he killed her.

Mr. Rascoe says that, ordinarily, juries are instructed that they are to assume the defendant is innocent, until he is proven guilty, but that in Frank's case, it was just the opposite.

Mr. Rascoe says that, during the trial, men stood up in the audience and shouted to the jury: "You'd better hang the Jew. If you don't, we'll hang him, and get you too."

The Chicago Tribune claims to be "the world's greatest newspaper," with a circulation of 500,000 for the Sunday edition.

It is therefore reasonable to suppose that at least two million people will get their ideas of the case from this special article, in which the public is told that Judge Roan allowed the audience to intimidate the jury by shouting their threats, to the jury, while the trial was in progress.

Of course, any one, who will stop and think a moment, will realize what an arrant falsehood that is.

Had any such thing occurred, the able, watchful, indefatigable lawyers who have been fighting nearly two years to save Frank's life, would have immediately moved a mistrial, and got it.

No such incident ever has occurred, in a Georgia court-room.

And no white man in Georgia was ever convicted on the evidence of a negro!

As a specimen of the misrepresentations which are misleading so many good people, take this extract from the article in the Chicago Tribune:

It has been declared by Burns, among others, that the circumstantial evidence warranting the retention of Conley as the suspected slayer was dropped and Conley was led to shoulder the blame upon Frank in somewhat the following manner:

"What do you know about this murder?"

"Nothing."

"Who do you think did it?"

"I don't know."

"How about Frank?"

"Yes. I confess. He's the one who did it."

"Sure he was. That's the fellow we want."

And forthwith Frank was locked up as a suspect.

In fact, the statements of Mr. Rascoe, like those of C.P. Connolly, are re-hashes from Wm. J. Burns.

Does not the Chicago Tribune know that Burns was expelled from the National Association of Police Chiefs?

Does not the Tribune know that Burns' confidential man in this Frank case, Lehon, was expelled from the Chicago police force, for blackmailing a woman of the town?

Does not the Tribune know that the detectives bribed Ragsdale and Barber, the preacher and the deacon, to swear this crime onto the negro, Jim Conley?

Does not the Tribune know that the official records in the U.S. Department of Justice disclose the fact that Attorney-General Wickersham, and President Taft set aside some convictions in the Oregon land cases, upon the overwhelming evidence that Burns is a crook, and corruptly obtained those convictions?

As already stated in this Magazine, Conley's evidence is not at all necessary to the conviction of Frank. Eliminate the negro entirely, and you have a dead case against this lewd young man, who had been pursuing the girl for nearly two months, and who, after setting a trap for her, on Memorial Day, 1913, had to use such violence to overcome her struggle for her virtue, that he killed her; and then had the diabolical cruelty to attack her character, after she was dead.

Mr. L.Z. Rosser telegraphed to a Northern newspaper a long statement in which he says—

Leo M. Frank is an educated, intelligent, normal man of a retiring, home making, home loving nature. He has lived a clean, honest, busy, unostentatious life, known by few outside of his own people. In the absence of the testimony of the negro, Jim Conley, a verdict of acquittal would have been inevitable.

If Mr. Rosser believed that Leo Frank was the pure young man and model husband, why did he sit silent while so many white girls and ladies swore to Frank's lascivious character?

Do you suppose that any power on earth could have produced twenty white women of Atlanta who would have sworn that Dr. John E. White's character is lascivious? Or that Judge Beverly Evans' character is lascivious? Or that Governor Slaton's character is lascivious?

The ex-lawyer from Montana—C.P. Connolly—says in Collier's:

The State contended that Frank murdered Mary Phagan on the second floor of the pencil factory. There was found four corpuscles of "blood"-a mere iota-on the second floor. The girl was brutally handled and bled freely, not only from the wound in her head, but from other parts of her body.

"Four corpuscles of blood—a mere iota—on the second floor."

That is what Connolly says. But what says the official record?

On page 26, Mr. R. P. Barrett, the machinist for Frank's factory, testifies, that on Monday morning, early, he discovered the blood spots, which were not there the Friday before! He says—

"The spot was about 4 or 5 inches in diameter, and little spots behind these in the rear—6 or 8 in number. It was blood."

Here we have one of Frank's responsible employees swearing positively to a five-inch splotch of blood, with 6 or 8 smaller spots leading up to the main spot, as large as the lid of the average dinner-pail; and Connolly tells the public that "four corpuscles, a mere iota," were all that were found!

When a man makes public statements of that kind, after having gone to Atlanta ostensibly to study the record, is he honestly trying to inform the public, or is he dishonestly trying to deceive it?

Mell Stanford swore, "These blood spots, were right in front of the ladies' dressing room," where Conley said he dropped the body of the girl, after Frank called on him for help.

Mrs. George Jefferson, also a worker in Frank's place, swore that they found the blood splotch, "as big as a fan."

Mrs. Jefferson had been working there five years. She knew paint spots when she saw them, and told of the maroon red, and red lime, and bright red, but she added, in answer to Frank's attorney, "That spot I saw was not one of those three paints."

She swore that the spot was not there Friday, April 25th. They found it Monday morning at about 6 or 7 o'clock. "We saw blood on the second floor, in front of the girl's dressing room. It was about as big as a fan."

The foreman of the metal room, Lemmie Quinn, also testified to seeing the blood spots, Monday morning. Quinn was Frank's own witness.

J.N. Starnes, police officer, testified (page 10 of the official record) that he saw the "splotches of blood." "I should judge the area of these spots to be a foot and a half."

Capt. Starnes saw the splotches of blood on Monday morning, April 28th, opposite the girl's dressing room; and they looked as if some white substance had been swept over them, in the effort to hide them.

Herbert Schiff, Leo Frank's assistant superintendent, also swore to the blood spots. He saw them Monday morning.

These witnesses were unimpeachable. Five of them worked under Frank, and were his trusted and experienced employees. They were corroborated by the doctors who examined the chips cut out of the floor. Those blood-stained chips are exhibits "E.," in the official record!

Yet, C.P. Connolly, sent down to Georgia to make an examination into actual facts, ignores the uncontradicted evidence, and tells the great American public, that on the second floor, where the State contends the crime was committed, there were found "four corpuscles of blood," only "a mere iota."

Upon consulting an approved Encyclopedia and Dictionary, which was constructed for the use of just such semi-barbarians as we Georgians, I find that the word "corpuscle" is synonymous with the word "atom." Further research in the same Encyclopedia, leads me to the knowledge, that an atom is such a very small thing that it cannot be made any smaller. It is, you may say, the Ultima Thule of smallness. The point of a cambric needle is a large sphere of action, compared to a corpuscle. The live animals that live in the water, and sweet milk, which you and I daily drink, are whales, buffaloes, and Montana lawyers, compared to a corpuscle. The germs, microbes, and malignant bacteria, that swim around invisibly in so many harmless-looking liquids, are behemoths, dragons and Burns detectives, compared to a corpuscle.

The smallest conceivable thing—invisible to the naked eye—is what Connolly says they found, on that second floor; and they not only found one of these infinitely invisible things, but four!

I want to deal nicely with Connolly, and therefore I will say that, as a lawyer and a journalist, I consider him a fairly good specimen of a corpuscle. What he is, as a teller and seller of "The Truth about the Frank case," I fear to say freely, lest the best Government the world ever saw arrest me again, for publishing disagreeable veracities.

Pardon me for taking your time with one more exposure of the impudent falsehoods that are being published about the evidence on which Frank was convicted. In his elaborate article in the Kansas City Star, A.B. Macdonald says—

The ashes and cinders were breathed before she died in the cellar, while she was fighting off Conley. In his drunken desperation lest she be heard and he be discovered he ripped a piece from her underskirt and tried to gag her with it. It was not strong enough. Then he grabbed the cord.

The testimony proved that cords like that were in the cellar. He tied it tightly around her neck. It was proved at the trial that a piece of the strip of underskirt was beneath the cord, and beneath the strip of skirt were cinders. That proves beyond doubt that both were put on in the cellar.

Having strangled her to death and eternal silence the negro had leisure to carry her back and hide her body at (fig. 12) where it was dark as midnight.

Then he sat down to write the notes. Against the wall opposite the boiler was a small, rude table with paper and pencil. Scattered around in the trash that came down from the floors above to be burned were sheets and pads of paper exactly like those upon which the notes were written. The pad from which one of the notes was torn was found by the body by Police Sergeant L.S. Dobbs, who so testified.

Here we have a graphic, gruesome picture of a fight between the girl and the negro, down in the cellar. He overcomes her, and in her death struggles, she breathes her nose, mouth and lungs full of ashes and cinders. The negro tears off a strip from her clothing, and binds it round her neck. "It was not strong enough. Then he grabbed the cord."

In the next line, Macdonald tells you that the strip of clothing was so strong that it remained underneath the cord, and that, beneath this strip, were cinders. "That proves beyond a doubt that they were both put on in the cellar."

It is sufficient to say that the evidence of Newt Lee, of Sergeant L.S. Dobbs, officer J.N. Starnes, and both the examining physicians, (Doctors Hurt and Harris) totally negatives the statement of Macdonald about the cinders under the girl's nails, the cinders packed into her face, and the cinders breathed into her nose, mouth and lungs. There was nothing of the kind. Macdonald made all that up, himself, aided by Connolly's imagination and Burns' imbecility.

(See official record, pages 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, and evidence of the doctors as per Index.)

But let me ask you to fix your attention on the specific statement of Macdonald, that the cord pressed down upon the strip of clothing, one being under the other, and that the cinders were under this inner choke-strip. Now, turn to page 48 of the official record, and see what Dr. Harris testified. He swore that she came to her death from "this cord" which had been tied tight around her neck. He did not say a word about any strip of clothing around her neck, under the cord, nor a word about any cinders, ashes or dust, under the cord—not one word!

Turn to page 46, and read the testimony of Dr. J.W. Hurt. He said, "There was a cord round her neck, and this cord was imbedded into the skin." Not a word about any strip of cloth under the cord! Not a word about cinders, ashes, or dust under the cord, or on her neck.

Sergeant Dobbs after saying that "the cord was around her neck, sunk into her flesh," added that "she also had a piece of her underclothing around her neck." "The cord was pulled tight and had cut into the flesh and tied just as tight as could be. The underclothing around her neck was not tight!"

Sergeant Dobbs, swearing that the cord had cut into the flesh, shows that there was no cushion of cloth to keep it from doing that very thing. Not a word did he say about cinders under her nails, under the cord, under the strip of underclothing, or in her nose, mouth and lungs.

In other words, the official record shows Macdonald's version of the evidence to be a reckless fabrication!

Can you picture to yourself, in the sane recess of your own mind, a Southern negro, raping and killing a white girl, and then dragging her body back to a place "where it was dark as midnight;" and then, after all his terrific struggle with his victim, hunting around in the trash to find a pencil and some pads—two different colors—and seating himself, leisurely, at "a small rude table near the boiler," to scribble a few lines of information to mankind as to how he came to commit the crime?

Can you picture to yourself a common Georgia nigger, killing a white woman in that way, and then seating himself near her corpse, deep down in a dark cellar, to indulge in literary composition?

Jim Conley, you see, had not only murdered the girl down there below the surface, but was writing notes close to where the dead body lay, with the intention of carrying the notes out there to where "it was as dark as midnight," to lay them by the dead girl's head.

Then, he meant to get so scared that he would violently break out of the basement door, into the alley, rather than walk out, as usual, up stairs.

Macdonald doesn't know much about Southern niggers, but he understands us white folks. Just tell us any old ludicrous yarn, and keep on telling it in the papers; and, if nobody denies it, we will all believe it.

There was not a scratch on the nose of the dead girl, and yet all these reckless writers tell the public she was held face downward by her murderer, and that her face was ground into the cinders, to smother her screams. How could the nose escape bruises in such a frightful process, and how could she fail to have cinders and coal-dust in her mouth and nose? There were none!

In the Philadelphia Public Ledger, there is a copyrighted article by Waldo G. Morse, whose legend runs, "Councillor, American Academy of Jurisprudence." Councillor Morse begins on the Frank case, by asking a question, and quoting himself in reply—

May a mob and a Court scare away your lawyers, a sheriff lock you away from the jury which convicts you, and may the sheriff then hold and hang you? Yes, say the Georgia Courts and so also says the United States District Judge in Georgia. Says the Supreme Court of the United States: "We will hear arguments as to that, and in the meantime we will defer the hanging."

The fancy picture of a Georgia mob, putting Rube Arnold, Luther Rosser, the Haas brothers, and the governor's own law firm to ignominious flight, and of the sheriff ruthlessly locking Frank away from the jury—and all this being done with the hearty approval of Judges Roan and Hill, the State Supreme Court, and Federal-judge William Newman—is certainly a novel picture to adorn the classic walls of the American Academy of Jurisprudence.

Councillor Morse proceeds as follows—

This is no mere question of a single life, but one for every man. Shall you be put on trial for your life or your liberty and shall timid or careless lawyers lose or dishonest lawyers barter away your rights?

We wish for the honor of the bar and the dignity of the Court that the lawyers had stood their ground and had braved the mob and that their client had joined in the defiance, inquiring from every juror, face to face, whether the verdict of guilty was the verdict of that individual juror. Such is due process of law.

Was Rosser "timid," in Frank's case? I would like to see Rosser, when one of his timid spells gets hold of him.

Were Rosser and Arnold and the Haas brothers not only timid, but "careless?" Councillor Morse, spokesman for the American Academy of Jurisprudence (whatever that is) accuses these Georgia lawyers of cowardice, or culpable negligence, in their defense of Leo Frank!

What? Is nobody to be spared? Shall no guilty Georgian escape? Must the propagandists of this Frank literature slaughter his own lawyers? Is it a misdemeanor, per se, to be Georgian?

"For the honor of the bar." Waldo Morse wishes that Rosser and Arnold, and Haas, and the governor's law firm, "had stood their ground." Then, they did not stand their ground, and they dishonored the bar.

That's terrible. Surely it is a cruel thing to stand Luther Rosser up before the universe, in this tremendous manner, and arraign him for professional cowardice. What say you, Luther? Are you guilty, or not guilty?

But Waldo Morse relentlessly continues—

Might not the result have been different? Jurors have been known to change their verdict when facing the accused. We hope that the Court may declare that no man and no State can leave the issue of life as a bagatelle to be played for, arranged about and jeopardized by Court and counsel in the absence of the man who may suffer.

So, you see, Frank's lawyers are accused, in a copyrighted indictment, of playing with their client's life, "as a bagatelle;" and of jeopardizing that life, with a levity which showed an utter lack of a due sense of professional responsibility.

That's mighty rough on Rosser, and Arnold, and Haas, and Governor Slaton's law firm.

What will be your opinion of Councillor Morse, when I tell you that Frank's lawyers did demand a poll of the jury, and each member was asked whether the verdict was his verdict, and each juror answered that it was.

And each juror, months afterwards, made written affidavit to the same effect, utterly repudiating the charges of mob intimidation.

Councillor Morse proceeds—

Shall a man charged with an infamous crime be faced by a jury of 12 men, each one ready to announce their verdict of his guilt? May he ask each man of the 12 whether the verdict be his? Yes, has answered the common law for centuries. The accused may not even waive or abandon this right.

That's absurd. The accused may waive or abandon "this right," and nearly every other. There are Courts in which the accused is constantly waiving and abandoning his Constitutional right to be indicted by a grand jury, and tried by a petit jury. In almost every case, the accused waives his legal right to actual arraignment, oral pleading, and a copy of the indictment. Almost invariably, he waives the useless and perfunctory right of polling the jury. If he likes, he can go to trial with eleven jurors, or less, and he may waive a legal disqualification of a juror. In fact, the accused, who can waive and abandon his right to the jury itself, can of course, waive any lesser right. This may not be good law in the American Academy of Jurisprudence, but it is good law among good lawyers.

Councillor Morse says that "for centuries" it has been the common-law right of the accused to ask each juror "whether the verdict be his." This cock-sure statement of what the English common-law has been "for centuries," would have had considerable weight, had the Councillor cited some authorities.

It was in 1765, that Sir William Blackstone published the first volume of his Commentaries; and at that time, the accused, in a capital case, did not even have the right to be defended by a lawyer. At that time, there were upwards of 116 violations of law, punishable by death, some of these capital offenses being petty larcenies, and others, trivial trespasses. In all those terrible cases, the accused was denied a lawyer, at common law; and these fearful conditions were not materially changed, until Sir Samuel Romilly began, his noble work of law reform, in 1808. At that time, it was death to pick a pocket, death to cut a tree in a park, death to filch from a bleachfield, death to steal a letter, death to kill a rabbit, death to pilfer five shilling's worth of stuff out of a store, death to forge a writing, death to steal a pig or a lamb, death to return home from transportation, death to write one's name on London bridge. Sir Samuel was not able to accomplish a great deal, before his suicide in 1818; but another great lawyer, Sir James Mackintosh, took up the work, Lord Brougham assisting. It was not until near the middle of the last century, that the Draconian code was stripped of most of its horrors, and the prisoner's counsel was allowed to address the jury. (See McCarthy's Epochs of Reform, pages 144 and 145. Mackenzie's The 19th Century, pages 124 and 125.) Therefore, when any Councillor for an American Academy of Jurisprudence glibly writes about what have been the common-law rights of the accused "for centuries," he makes himself ridiculous.

As a general rule, a prisoner may waive any legal privilege; and whatever he may waive, his attorney may waive; and this waiver can be made after the trial and will relate back to the time when he was entitled to the privilege. This waiver may be expressed, or it may be implied; it may be in words, and it may be in conduct.

In Blackstone's Commentaries, nothing is said on the point of the prisoner's presence, when the verdict comes in. Unquestionably, it is the better practice for him to be in court. But if his attorneys are present, and they demand a poll of the jury, expressly waiving the presence of their client, they have done for the accused all that he could do for himself, were he in court—for the prisoner is not allowed to ask the jurors any questions. The judge does that. Hence, Frank lost nothing whatever by his absence; and when he failed to make that point, as he stood in court to be sentenced and was asked by the judge, "What have you to say why sentence should not be pronounced on you?" he ratified the waiver his lawyers had made. He continued that ratification, for a whole year.

Not until after two motions for new trial had been filed, did Frank raise the point about his absence at the time the verdict came in; and, if he is set free on that point, the world will suspect that Rosser and Arnold, laid a trap for the judge.

Does it seem good law to Councillor Morse, that a man whose guilt is made manifest by the official record, should be turned loose, to go scot free, on a technical point, which involves the repudiation of his own lawyers, and the retraction of his own ratification which had lasted a year? Is there no such thing as a waiver by one's attorneys and a ratification by one's prolonged acquiescence?

Now before going into close reasoning on the established facts in the case, allow me to call your attention to this point:

Whoever wrote those notes that were found beside the body seems to say that she had been sexually used. "Play with me." "Said he would love me." "Laid down." "Play like night witch did it," but that long tall black negro "did (it) by hisself."

Those words are inconsistent with a crime whose main purpose was murder. Uppermost in the mind of the man who dictated those notes, was quite another idea. Consistent with that idea, and not with murder alone, are the words "Play with me, said he would love me, laid down," (with me) "and play like the night witch did it."

All have claimed that the words "night witch" meant "night watch." It may not be so. For the present, I only ask you to consider that the State's theory all along, has been that Leo Frank was after this girl, to enjoy her sexually, and that the murder was a crime incident to her resistance.

The girl worked for Frank, and he knew her well. He had sought to push his attentions on her. She had repulsed him. She had told her friend George Epps that she was afraid of him, on account of the way he had acted toward her.

He had refused, on Friday afternoon, to let Helen Ferguson have Mary's pay-envelope, containing the pitiful sum of one dollar and twenty cents. He thus made it necessary for Mary to come in person for it, which she was sure to do, next day, since the universal Saturday custom is, to pay for things bought during the preceding week and buy things, for the next.

Why did not Frank give Mary's pay envelope to Helen, when Helen asked for it, on Friday? It had been the habit of Helen to get Mary's envelope, and Frank could hardly have been ignorant of the fact.

Did he refuse to let Helen have Mary's pay, because it was not good business?

That hypothesis falls, when we examine Frank's own statement to the jury. On page 179 of the record, he tells the jury that Mattie Smith came for her pay-envelope on Saturday morning, the 26th of April, and she asked for that of her sister-in-law, also, "and I went to the safe….and got out the package…and gave her the required two envelopes."

Therefore, Frank himself was in the habit of letting one employee have another's pay envelope. On that same morning, he gave the pay-envelopes of two of the boys to their fathers, Graham and Burdette. (Page 181.)

Why did Frank make an exception of Mary Phagan, this one time? Why did he discriminate against her, and only her, that week-end?

Be the answer what it may, the girl, all diked out in her cheap little finery for Memorial Day, comes with her smart fresh lavender dress, the flowers on her hat, the ribbons on her dress, her gay parasol, and her best stockings and silk garters—comes into the heart of the great city, about noon, goes immediately to Frank's office for her one dollar and twenty cents, is traced by evidence, which Frank dared not deny, into his office—and, is never more seen alive.

Is there any reasonable person, on the face of God's earth, who wouldn't say Frank must account for that girl?

When a mountain of evidence piled up, on the fact of the girl's going to him, he then admitted that she did go to him, somewhere around 12 o'clock that day.

He says that a little girl whom he afterwards learned to be Mary Phagan, came to him for her pay-envelope.

He pretended not to know that a girl of her name worked for him, until he consulted the pay-roll! He went through the motion of looking at the pay-roll for the purpose of ascertaining whether such a human being worked in his place! After having found her name on the list, he then admitted that a girl named Mary Phagan had been working there.

What sort of impression does this make on you, in view of the fact that four white witnesses swore they had seen Frank talk to her, and that, in doing so, he called her "Mary?"

Why did Frank, when her dead body was found in the basement, feign not to know her, and say that he would have to consult the pay-roll?

The girl, dressed up for a Holiday, was in Frank's office, at about the noon hour of that fatal day—and those two were alone!

Frank is driven to that dreadful admission. Inexorable proofs left him no option.

By his own confession, he is alone with the girl, the last time any mortal eye sees her alive!

She is in the flush of youthful bloom. She is nearly fourteen years old, buxom, and rather large for her age. She has rosy cheeks, bright blue eyes, and golden hair. She is well-made, in perfect health, as tempting a morsel as ever heated depraved appetite. Did Leo Frank desire to possess the girl? Was he the kind of married man who runs after fresh little girls? Had he given evidence, in that very factory, of his lascivious character?

The white ladies and girls whose names have already been given, swore that Frank was just that kind of a man; and neither Frank nor his battalion of lawyers have ever dared to ask those white women to go into details, and tell why they swore he was depraved!

Does it make no impression on your mind, when you consider that tremendous fact?

We start out, then, with a depraved young married man whose conduct, in that very place, is proved to have been lascivious. Did he desire Mary Phagan? Had he "tried" her? Did he want to "try" her, again?

One white girl swore that she had seen Frank with this hand on Mary's shoulder and his face almost in hers, talking to her. One white boy swore that he had seen Mary shrinking away from Frank's suspicious advances. Another white boy swore that Mary said she was suspicious and afraid of Frank. Another white girl swore she heard him calling her "Mary," in close conversation.

How many witnesses are necessary to prove that the licentious young Jew lusted after this Gentile girl?

The record gives you four.

(See the evidence of Ruth Robinson, J.M. Gantt, Dewey Howell and W.E. Turner.)

Why, then, did she continue to work there?

She needed the money, and felt strong in her virtue: she never dreamed of violence.

She kept on working, as many poor girls do, who cannot help themselves. Freedom to choose, is not the luxury of the poor.

But let us pass on. The fatal day comes, and Mary comes, and then her light goes out—the pretty little girl who had dressed up for the Holiday and gone out, radiant with youth and health and beauty, to enjoy it, as other young girls all over the South were doing. She goes into Frank's own private office, and that's the last of her.

What became of her? Tell us, Luther Rosser! Tell us, Herbert Haas! Tell us, Nathan Strauss! Tell us, Adolph Ochs! Tell us, Rabbi Marx! Tell us, William Randolph Hearst!

What became of our girl?

YOUR MAN, FRANK, HAD HER LAST: WHAT DID HE DO WITH HER?

So far as I can discover, the only theory advanced by the defenders of Leo Frank, is hung upon Jim Conley. They claim that Jim darted out upon Mary as she stepped aside on the first floor, cut her scalp with a blow, rendered her unconscious, pushed her through the scuttle-hole, and then went down after her, tied the cord around her neck, choked her to death, hid the body, wrote the notes, and broke out by the basement door.

If the defense has any other theory than this, I have been unable to find it. And they must have a theory, for the girl was killed, in the factory, immediately after she left Frank's private office. There is the undeniable fact of the murdered girl, and no matter what may be the "jungle fury" of the Atlanta "mob," and of the "semi-barbarians" of Georgia, these mobs and barbarians did not kill the girl.

Either the Cornell graduate did it, or Jim Conley did it.

Did Jim Conley do it? If so, how, and why? What was his motive, and what was his method?

The defense claims that he struck her the blow, splitting the scalp, on the first floor, where he worked, immediately after she left Frank's office on the second floor.

They claim that the negro then dragged the unconscious body to the scuttle-hole, and flung her down that ladder.

What sort of hole is it? All the evidence concurs in its being a small opening in the floor, with a trap-door over it, and only large enough to admit one person at a time. (It is two-feet square.)

Reaching from the opening of this hole, down to the floor of the basement, is a ladder, with open rungs.

Now, when Jim Conley hit the girl in the head, and split her scalp, they claim he pushed her through the trap-door, so that she would fall into the basement below.

But how could the limp and bleeding body fall down that ladder, striking rung after rung, on its way down, without leaving bloodmarks on the ladder, and without the face and head of poor dying Mary being all bunged up, broken and cut open, by the repeated beatings against the "rounds" of the ladder?

How could that bleeding head have lain at the foot of the ladder, without leaving an accusing puddle of blood? How could that bleeding body, still alive, have been choked to death in the cellar, leaving no blood on the basement floor, none on the ladder, none at the trap-door, none on the table where they claim the notes were written, and none on the pads and the notes?

Not a particle of the testimony points suspicion toward the negro, before the crime. He lived with a kept negro woman, as so many of his race do; but he had never been accused of any offense more grave than the police common-place, "Disorderly." (His fines range from $1.75 to $15.00.)

He was at the factory on the day of the crime, and Mrs. Arthur White saw him sitting quietly on the first floor, where it was his business to be. After the crime, there was never any evidence discovered against him. He lied as to his doings at the time of the crime, but all of these were consistent with the plan of Frank and Conley to shield each other. Frank was just as careful to keep suspicion from settling on the negro, as the negro was to keep it from settling on Frank.

You would naturally suppose that the white man, reasoning swiftly, would have realized that the crime lay between himself and the negro; and that, as he knew himself to be innocent, he knew the negro must be guilty.

Any white man, under those circumstances, would at once have seen, that only himself or the negro could have done the deed, since no others had the opportunity.

Hence, the white man, being conscious of innocence, and bold in it, would have said to the police, to the detectives, to the world—

"No other man could have done this thing, except Jim Conley or myself; and, since I did not do it, Jim Conley did. I demand that you arrest him, at once, and let me face him!"

Did Frank do that? Did the Cornell graduate break out into a fury of injured innocence, point to Conley as the criminal, and go to him and question him, as to his actions, that fatal day?

No, indeed. Frank never once hinted Conley's guilt. Frank never once asked to be allowed to face Conley. Frank hung his head when he talked to Newt Lee; trembled and shook and swallowed and drew deep breaths, and kept shuffling his legs and couldn't sit still; walked nervously to the windows and wrung his hands a dozen times within a few minutes; insinuated that J.M. Gantt might have committed the crime; and suggested that Newt Lee's house ought to be searched; but never a single time threw suspicion on Jim Conley, or suggested that Jim's house ought to be searched.

Did the negro want to rob somebody in the factory? Could he have chosen a worse place? Could he have chosen a poorer victim, and one more likely to make a stout fight?

Mary had not worked that week, except a small fraction of the time, and Jim knew it. Therefore he knew that her pay-envelope held less than that of any of the girls!

Did Jim Conley want to assault some woman in the factory? Could he have chosen a worse time and place, if he did it on the first floor at the front, where white people were coming and going; and where his boss, Mr. Frank, might come down stairs any minute, on his way to his noon meal?

No negro that ever lived would attempt to outrage a white woman, almost in the presence of a white man.

Between the hour of 12:05 and 12:10 Monteen Stover walked up the stairs from the first floor to Frank's office on the second, and she walked right through his outer office into his inner office—and Frank was not there!

She waited 5 minutes, and left. She saw nobody. She did not see Conley, and she did not see Frank.

Where were they? And where was Mary Phagan?

It is useless to talk about street-car schedules, about the variations in clocks, about the condition of cabbage in the stomach, and about the menstrual blood, and all that sort of secondary matter.

The vital point is this—

Where was Mary, and where was Frank, and where was Conley, during the 25 minutes, before Mrs. White saw both Frank, and Conley?

Above all, where was Frank when Monteen Stover went through both his offices, the inner as well as the outer, and couldn't find him?

She wanted to find him, for she needed her money. She wanted to find him, for she lingered 5 minutes.

Where was Frank, while Monteen was in his office, and was waiting for him?

THAT'S THE POINT IN THE CASE: all else is subordinate.

Rosser and Arnold are splendid lawyers; no one doubts that. They were employed on account of their pre-eminent rank at the bar. I have been with them in great cases, and I know that whatever it is possible to do in a forensic battle, they are able to do.

Do you suppose for one moment that Rosser and Arnold did not see the terrible significance of Monteen's evidence?

They saw it clearly. And they made frantic efforts to get away from it. How?

First, they put up Lemmie Quinn, another employee of Frank, to testify that he had gone to Frank's office, at 12:20, that Saturday, and found Frank there.

But Lemmie Quinn's evidence recoiled on Frank, hurting the case badly. Why? Because two white ladies, whom the Defendant put up, as his witnesses, swore positively that they were in the factory just before noon, and that after they left Frank, they went to a café, where they found Lemmie Quinn; and he told them he had just been up to the office to see Frank.

Mrs. Freeman, one of the ladies, swore that as she was leaving the factory, she looked at Frank's own clock, and it was a quarter to twelve.