Atlanta Georgian

August 8th, 1913

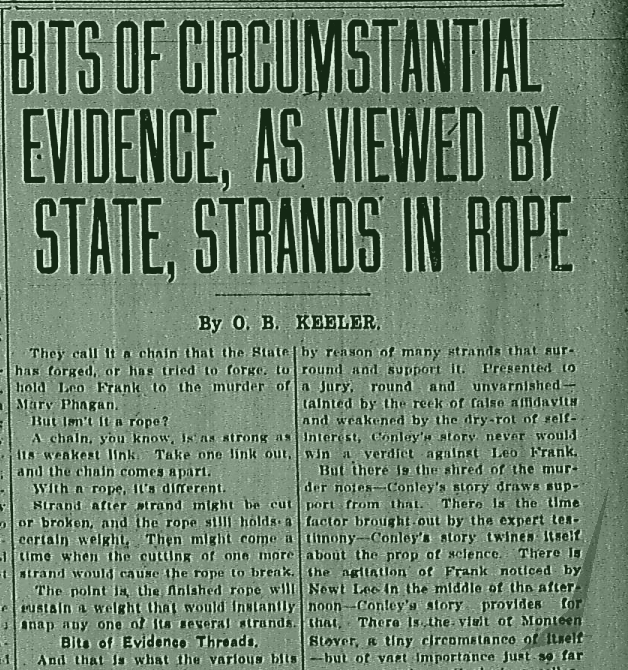

By O. B. KEELER.

They call it a chain that the State has forged, or has tried to forge, to hold Leo Frank to the murder of Mary Phagan.

But isn't it a rope?

A chain, you know, is as strong as its weakest link. Take one link out, and the chain comes apart.

With a rope, it's different.

Strand after strand might be cut or broken, and the rope still holds a certain weight. Then might come a time when the cutting of one more strand would cause the rope to break.

The point is, the finished rope will sustain a weight that would instantly snap any one of its several strands.

Bits of Evidence Threads.

And that is what the various bits of circumstantial evidence might better be called—strands or threads.

Edgar Allen Poe, in "The Mystery of Marie Roget," has nearly exhausted the philosophical phase of accumulative circumstance and its relation to evidence.

Applying the system of the well-known Dupin to the case in point—and REGARDING IT, BE IT UNDERSTOOD, STRICTLY FROM THE STATE'S VIEWPOINT—an analysis of part of the evidence against Leo Frank follows:

First off, the isolated circumstance of Conley's ability to write would seem as futile as a smoke wreath in sustaining any weight of evidence, except against Conley himself.

But to the fact is added the fact that Frank knew Conley could write.

Still, the thread is flimsy, and even connected with the case against Frank, would appear worthless.

Six Deductions Seen.

But when it develops that Frank knowing Conley could write, and knowing the police were trying to find the author of the murder notes—when Frank, well aware of these things, did not inform the police that Conley was lying when he said he could not write, the following deductions appear:

(1) That Frank did not want to connect Conley with the murder notes which (2) would have been the natural and prompt inclination of a suspected man who knew nothing of the crime himself, so that (3) it appeared Frank knew something of the murder, and (4) knew that Conley knew he knew something of the murder, which (5) justified the conclusion on the part of the State that Frank feared to implicate Conley, lest (6) Conley, in turn, tell something that would implicate him.

Of course, this stand may be broken entirely by the defense, showing Frank never knew the police were ignorant of Conley's ability to write before the police learned it themselves.

But there is one pretty substantial stand of evidence, as the State sees it—and all having its genesis in the simple fact that Conley knew how to write, and at first denied it.

But that strand of itself surely would fail to carry the burden of the case. There must be others.

Even Conley's story is strong only by reason of many strands that surround and support it. Presented to a jury, round and unvarnished—tainted by the reek of false affidavits and weakened by the dry-rot of self-interest, Conley's story never would win a verdict against Leo Frank.

But there is the shred of the murder notes—Conley's story draws support from that. There is the time factor brought out by the expert testimony—Conley's story twines itself about the prop of science. There is the agitation of Frank noticed by Newt Lee in the middle of the afternoon—Conley's story provides for that. There is the visit of Monteen Stover, a tiny circumstance of itself—but of vast importance just so far as it strengthens Conley's recollection of exact time.

And it is by reason of the rope already well along in the twisting that a hundred other little circumstances become significant that of themselves would be lighter than the air drawn dagger that troubled the dreams of Macbeth.

They fit in with the twisting of the rope.

Will the Rope Hold?

There is Frank's agitation at home and at the factory. There is the ugly story of habitual "chats" at the factory, guarded by Conley as watchman. And the sending away of Newt Lee that afternoon. And the seeing of Conley by Mrs. White, "loitering" at the place he fixes for himself as watchman, and at the time. And the alleged reluctance of Frank to confront Conley at the jail.

And all the rest of it.

So many little incidents, and most of them small to triviality in themselves.

The point is, each strengthens the other, until the fragile threads become a rope.

Will it hold after Frank's lawyers have presented their side of the case.

The jury must decide.

* * *

- Monday, 28th April 1913 10,000 Throng Morgue to See Body of Victim [Last Updated On: September 13th, 2023] [Originally Added On: January 18th, 2023]

- Monday, 28th April 1913 12-Year-Old Girl Sobs Her Love for Slain Child [Last Updated On: September 13th, 2023] [Originally Added On: February 9th, 2023]

- Monday, 28th April 1913 3 Youths Seen Leading Along a Reeling Girl [Last Updated On: September 13th, 2023] [Originally Added On: February 10th, 2023]

- Monday, 28th April 1913 Arrested as Girl’s Slayer [Last Updated On: September 13th, 2023] [Originally Added On: January 31st, 2023]

- Monday, 28th April 1913 Body Dragged by Deadly Cord After Terrific Fight [Last Updated On: September 13th, 2023] [Originally Added On: February 8th, 2023]

- Monday, 28th April 1913 Chief and Sleuths Trace Steps in Slaying of Girl [Last Updated On: September 13th, 2023] [Originally Added On: February 7th, 2023]

- Monday, 28th April 1913 City Chemist Tests Stains For Blood [Last Updated On: September 13th, 2023] [Originally Added On: February 6th, 2023]

- Monday, 28th April 1913 Gantt Was Infatuated With Girl; at Factory Saturday [Last Updated On: September 3rd, 2023] [Originally Added On: February 5th, 2023]

- Monday, 28th April 1913 Girl and His Landlady Defend Mullinax [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: February 4th, 2023]

- Monday, 28th April 1913 Girl to Be Buried in Marietta To-morrow [Last Updated On: September 13th, 2023] [Originally Added On: February 3rd, 2023]

- Monday, 28th April 1913 Girl’s Grandfather Vows Vengeance [Last Updated On: September 13th, 2023] [Originally Added On: February 2nd, 2023]

- Monday, the 28th Day of April-1913, Horrible Mistake, Pleads Arthur Mullinax, Denying Crime, The Atlanta Georgian [Last Updated On: November 18th, 2023] [Originally Added On: February 1st, 2023]

- Monday, 28th April 1913 “I Could Trust Mary Anywhere,” Her Weeping Mother Says [Last Updated On: November 23rd, 2023] [Originally Added On: February 11th, 2023]

- Monday, 28th April 1913 Incoherent Notes Add to Mystery in Strangling Case [Last Updated On: November 18th, 2023] [Originally Added On: January 8th, 2023]

- Monday, the 28th Day of April-1913, Lifelong Friend Saw Girl and Man After Midnight, Hearst's Atlanta Georgian [Last Updated On: November 18th, 2023] [Originally Added On: January 30th, 2023]

- Monday, 28th April 1913 Look for Negro to Break Down [Last Updated On: September 14th, 2023] [Originally Added On: January 29th, 2023]

- Monday, 28th April 1913 Mullinax Blundered in Statement, Say Police [Last Updated On: September 14th, 2023] [Originally Added On: January 28th, 2023]

- Monday, 28th April 1913 Negro is Not Guilty, Says Factory Head [Last Updated On: September 14th, 2023] [Originally Added On: January 27th, 2023]

- Monday, 28th April 1913 Neighbors of Slain Girl Cry for Vengeance [Last Updated On: September 14th, 2023] [Originally Added On: January 26th, 2023]

- Monday, 28th April 1913 Pinkertons Take Up Hunt for Slayer [Last Updated On: September 14th, 2023] [Originally Added On: January 25th, 2023]

- Monday, 28th April 1913 Playful Girl With Not a Bad Thought [Last Updated On: September 14th, 2023] [Originally Added On: February 12th, 2023]

- Monday, 28th April 1913 Police Question Factory Superintendent [Last Updated On: September 15th, 2023] [Originally Added On: January 24th, 2023]

- Monday, 28th April 1913 Slain Girl Modest and Quiet, He Says [Last Updated On: September 15th, 2023] [Originally Added On: January 23rd, 2023]

- Monday, 28th April 1913 Soda Clerk Sought in Phagan Mystery [Last Updated On: September 15th, 2023] [Originally Added On: January 22nd, 2023]

- Monday, 28th April 1913 Story of the Killing as the Meager Facts Reveal It [Last Updated On: September 15th, 2023] [Originally Added On: January 21st, 2023]

- Monday, 28th April 1913 Suspect Gantt Tells His Own Story [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: January 20th, 2023]

- Monday, 28th April 1913 Where and With Whom Was Mary Phagan Before End? [Last Updated On: September 15th, 2023] [Originally Added On: January 19th, 2023]

- Tuesday, 29th April 1913 Bartender Confirms Gantts Statement [Last Updated On: September 15th, 2023] [Originally Added On: January 16th, 2023]

- Tuesday, 29th April 1913 Charge is Basest of Lies, Declares Gantt [Last Updated On: September 15th, 2023] [Originally Added On: January 15th, 2023]

- Tuesday, 29th April 1913 Factory Employee May Be Taken Any Moment [Last Updated On: September 15th, 2023] [Originally Added On: January 14th, 2023]

- Tuesday, 29th April 1913 Factory Head Frank and Watchman Newt Lee are Sweated by Police [Last Updated On: September 15th, 2023] [Originally Added On: January 13th, 2023]

- Tuesday, 29th April 1913 Former Playmates Meet Girl’s Body at Marietta [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: January 12th, 2023]

- Tuesday, 29th April 1913 Guilt Will Be Fixed Detectives Declare [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: January 11th, 2023]

- Tuesday, 29th April 1913 I Feel as Though I Could Die, Sobs Mary Phagans Grief-Stricken Sister [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: January 17th, 2023]

- Tuesday, 29th April 1913 Is the Guilty Man Among Those Held? [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: January 10th, 2023]

- Tuesday, 29th April 1913 Keeper of Rooming House Enters Case [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: January 9th, 2023]

- Tuesday, 29th April 1913 Loyalty Sends Girl to Defend Mullinax [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 15th, 2022]

- Tuesday, 29th April 1913 Negro Watchman is Accused by Slain Girl’s Stepfather [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 14th, 2022]

- Tuesday, 29th April 1913 Nude Dancers Pictures Upon Factory Walls [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 13th, 2022]

- Tuesday, 29th April 1913 Pastor Prays for Justice at Girls Funeral [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 12th, 2022]

- Tuesday, 29th April 1913 Seek Clew in Queer Words in Odd Notes [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 11th, 2022]

- Tuesday, 29th April 1913 Slayers Hand Print Left On Arm Of Girl [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 10th, 2022]

- Wednesday, 30th April 1913 Boy Sweetheart Says Girl Was to Meet Him Saturday [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 20th, 2022]

- Wednesday, 30th April 1913 City Offers $1,000 as Phagan Case Reward [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 19th, 2022]

- Wednesday, 30th April 1913 Clock Misses Add Mystery to Phagan Case [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 31st, 2022]

- Wednesday, 30th April 1913 Confirms Lee’s Story of Shirt [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: January 1st, 2023]

- Wednesday, 30th April 1913 Girl’s Death Laid to Factory Evils [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: January 4th, 2023]

- Wednesday, 30th April 1913 Great Crowd at Phagan Inquest [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: January 3rd, 2023]

- Wednesday, 30th April 1913 Handwriting of Notes is Identified as Newt Lees [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 21st, 2022]

- Wednesday, 30th April 1913 Leo Frank’s Friends Denounce Detention [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 30th, 2022]

- Wednesday, 30th April 1913 Looks Like Frank is Trying to Put Crime on Me, Says Lee [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 24th, 2022]

- Wednesday, 30th April 1913 Machinist Tells of Hair Found in Factory Lathe [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 22nd, 2022]

- Wednesday, 30th April 1913 Mother Prays That Son May Be Released [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 29th, 2022]

- Wednesday, 30th April 1913 Net Closing About Lee, Says Lanford [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 23rd, 2022]

- Wednesday, 30th April 1913 Newt Lee on Stand at Inquest Tells His Side of Phagan Case [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: January 7th, 2023]

- Wednesday, 30th April 1913 Newt Lees Testimony as He Gave It at the Inquest [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: January 6th, 2023]

- Wednesday, 30th April 1913 Policeman Says Body Was Dragged From Elevator [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: January 5th, 2023]

- Wednesday, 30th April 1913 Reward of $1,000 Urged by Mayor [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 18th, 2022]

- Wednesday, 30th April 1913 Sergeant Brown Tells His Story of Finding of Body [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 28th, 2022]

- Wednesday, 30th April 1913 Sisters New Story Likely to Clear Gantt as Suspect [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 16th, 2022]

- Wednesday, 30th April 1913 Tells Jury He Saw Girl and Mullinax Together [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 25th, 2022]

- Wednesday, 30th April 1913 Tells of Watchman Lee Explaining the Notes [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 27th, 2022]

- Wednesday, 30th April 1913 Went Down Scuttle Hole on Ladder to Reach Body [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: January 2nd, 2023]

- Wednesday, 30th April 1913 Witness Saw Slain Girl and Man at Factory Door [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 26th, 2022]

- Wednesday, 30th April 1913 Writing Test Points to Negro [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 17th, 2022]

- Thursday, 1st May 1913 State Enters Phagan Case; Frank and Lee are Taken to Tower [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 9th, 2022]

- Thursday, 1st May 1913 Terminal Official Certain He Saw Girl [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 8th, 2022]

- Friday, 2nd May 1913 Dorsey Puts Own Sleuths Onto Phagan Slaying Case [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 7th, 2022]

- Friday, 2nd May 1913 Police Still Puzzled by Mystery of Phagan Case [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 6th, 2022]

- Saturday, 3rd May 1913 Analysis of Blood Stains May Solve Phagan Mystery [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 5th, 2022]

- Sunday, 4th May 1913 Dr. John E. White Writes on the Phagan Case [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2022]

- Sunday, 4th May 1913 Gov. Brown on the Phagan Case [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 4th, 2022]

- Sunday, 4th May 1913 Grand Jury to Take Up Phagan Case To-morrow [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 3rd, 2022]

- Sunday, 4th May 1913 Old Police Reporter Analyzes Mystery Phagan Case Solution Far Off, He Says [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 2nd, 2022]

- Sunday, 4th May 1913 Slayer of Mary Phagan May Still be at Large [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: November 30th, 2022]

- Monday, 5th May 1913 Coroners Jury Likely to Hold Both Prisoners [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: November 24th, 2022]

- Monday, 5th May 1913 Crowds at Phagan Inquest [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: November 29th, 2022]

- Monday, 5th May 1913 Frank on Witness Stand [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: November 26th, 2022]

- Monday, 5th May 1913 Judge Charges Grand Jury to Go Deeply Into Phagan Mystery [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: November 28th, 2022]

- Monday, 5th May 1913 Judge W. D. Ellis Charges Grand Jury to Probe into Phagan Slaying Mystery [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: November 27th, 2022]

- Monday, 5th May 1913 Phagan Girl’s Body Exhumed [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: November 25th, 2022]

- Tuesday, 6th May 1913 Bowen Still Held by Houston Police in the Phagan Case [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: November 22nd, 2022]

- Tuesday, 6th May 1913 Brother Declares Bowen Left Georgia in August [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: November 21st, 2022]

- Tuesday, 6th May 1913 Frank’s Testimony Fails to Lift Veil of Mystery [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: November 18th, 2022]

- Tuesday, 6th May 1913 How Frank Spent Day of Tragedy [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: November 20th, 2022]

- Tuesday, 6th May 1913 Newest Clews in Phagan Case Not Yet Public [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: November 23rd, 2022]

- Tuesday, 6th May 1913 Phagan Case and the Solicitor Generals Power Under Law—Dorsey Hasnt Encroached on Coroner [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: November 19th, 2022]

- Wednesday, 7th May 1913 Employe of Lunch Stand Near Pencil Factory is Trailed to Alabama [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: November 16th, 2022]

- Wednesday, 7th May 1913 Lee is Quizzed by Dorsey for New Evidence [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: November 15th, 2022]

- Wednesday, 7th May 1913 Phagan Girls Body Again Exhumed for Finger-Print Clews [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: November 14th, 2022]

- Wednesday, 7th May 1913 Solicitor Dorsey Orders Body Exhumed in the Hope of Getting New Evidence [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: November 17th, 2022]

- Thursday, 8th May 1913 Another Clew in Phagan Case is Worthless [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: November 5th, 2022]

- Thursday, 8th May 1913 Black Testifies Quinn Denied Visiting Factory [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: October 31st, 2022]

- Thursday, 8th May 1913 Boots Rogers Tells How Body Was Found [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: November 10th, 2022]

- Thursday, 8th May 1913 Didnt See Girl Late Saturday, He Admits [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: November 11th, 2022]

- Thursday, 8th May 1913 Frank Answers Questions Nervously When Recalled [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: November 3rd, 2022]

- Thursday, 8th May 1913 Frank of Nervous Nature; Says Superintendent Aide [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: November 1st, 2022]

- Thursday, 8th May 1913 Girl Employe on Fourth Floor of Factory Saturday [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: November 6th, 2022]

- Thursday, 8th May 1913 Grand Jury to Sift the Evidence in the Phagan Case Within the Next Few Days [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: November 9th, 2022]

- Thursday, 8th May 1913 Inquest Scene is Dramatic in its Tenseness [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: November 13th, 2022]

- Thursday, 8th May 1913 Lee Repeats His Private Conversation With Frank [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: October 30th, 2022]

- Thursday, 8th May 1913 Leo Frank is Again Quizzed by Coroner [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: November 4th, 2022]

- Thursday, 8th May 1913 Pinkerton Detective Tells of Call From Factory Head [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: November 2nd, 2022]

- Thursday, 8th May 1913 Police Still Withhold Evidence; Frank To Be Examined on New Lines [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: November 12th, 2022]

- Thursday, 8th May 1913 Quinn, Foreman Over Slain Girl, Tells of Seeing Frank [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: November 8th, 2022]

- Thursday, 8th May 1913 Stenographer in Factory Office on Witness Stand [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: November 7th, 2022]

- Friday, 9th May 1913 Best Detective in America Now is on Case, Says Dorsey [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: October 29th, 2022]

- Saturday, 10th May 1913 Guard of Secrecy is Thrown About Phagan Search by Solicitor [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: October 28th, 2022]

- Sunday, 11th May 1913 Caught Frank With Girl in Park, He Says [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: October 25th, 2022]

- Sunday, 11th May 1913 Frank is Awaiting Action of the Grand Jury Calmly [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: October 24th, 2022]

- Sunday, 11th May 1913 Mary Phagans Death Only Assured Fact Developed [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: October 26th, 2022]

- Sunday, 11th May 1913 Weak Evidence Against Men in Phagan Slaying [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: October 27th, 2022]

- Monday, 12th May 1913 Burns Called into Phagan Mystery; On Way From Europe [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: October 23rd, 2022]

- Monday, 12th May 1913 Phagan Case is Delayed [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: October 22nd, 2022]

- Tuesday, 13th May 1913 Frank’s Life in Tower [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: October 20th, 2022]

- Tuesday, 13th May 1913 Mother Thinks Police Are Doing Their Best [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: October 19th, 2022]

- Tuesday, 13th May 1913 New Theory is Offered in Phagan Mystery [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: October 21st, 2022]

- Wednesday, 14th May 1913 Friends Say Franks Actions Point to Innocence [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: October 17th, 2022]

- Wednesday, 14th May 1913 Secret Hunt by Burns in Mystery is Likely [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: October 18th, 2022]

- Thursday, 15th May 1913 Burns Investigator Will Probe Slaying [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: October 16th, 2022]

- Friday, 16th May 1913 $1,000 Offered Burns to Take Phagan Case [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: October 13th, 2022]

- Friday, 16th May 1913 Burns Hunt for Phagan Slayer Begun [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: October 15th, 2022]

- Friday, 16th May 1913 Secret Probe Began by Burns Agent into the Phagan Mystery [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: October 14th, 2022]

- Saturday, 17th May 1913 New Phagan Witnesses Have Been Found [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: October 12th, 2022]

- Sunday, 18th May 1913 Burns, Called in as Last Resort, Faces Cold Trail in Baffling Phagan Case [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: October 11th, 2022]

- Sunday, 18th May 1913 Burns Sleuth Makes Report in Phagan Case [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: October 10th, 2022]

- Sunday, 18th May 1913 Greeks Add to Fund to Solve Phagan Case [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: October 9th, 2022]

- Monday, 19th May 1913 Burns Agent Outlines Phagan Theory [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: October 7th, 2022]

- Monday, 19th May 1913 Burns Eager to Solve Phagan Case [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: October 8th, 2022]

- Tuesday, 20th May 1913 Cases Ready Against Lee and Leo Frank [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: October 6th, 2022]

- Wednesday, 21st May 1913 T. B. Felder Repudiates Report of Activity for Frank [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: October 5th, 2022]

- Thursday, 22nd May 1913 Grand Jury Wont Hear Leo Frank or Lee [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: October 4th, 2022]

- Friday, 23rd May 1913 Dictograph Record Used Against Felder [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: September 28th, 2022]

- Friday, 23rd May 1913 Felder Denies Phagan Bribe; Calls Colyar Crook and Liar [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: September 30th, 2022]

- Friday, 23rd May 1913 Felder Denies Phagan Bribery; Dictograph Record Used Against Felder [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: October 2nd, 2022]

- Friday, 23rd May 1913 Frank Feeling Fine But Will Not Discuss His Case [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: October 1st, 2022]

- Friday, 23rd May 1913 Here is Affidavit Charging Bribery [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: September 29th, 2022]

- Friday, 23rd May 1913 Indictment of Both Lee and Frank is Asked [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: October 3rd, 2022]

- Saturday, 24th May 1913 Beavers Says He Will Seek Indictments [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: September 16th, 2022]

- Saturday, 24th May 1913 Blease Ironic in Comments on Felder Trap [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: September 17th, 2022]

- Saturday, 24th May 1913 Colyar Called Convict and Insane [Last Updated On: September 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: September 20th, 2022]

- Saturday, 24th May 1913 Colyar Held for Forgery [Last Updated On: September 17th, 2023] [Originally Added On: September 26th, 2022]

- Saturday, 24th May 1913 Dictograph Catches Mayor in Net [Last Updated On: September 17th, 2023] [Originally Added On: September 27th, 2022]

- Saturday, 24th May 1913 Dictograph Record Alleged Bribe Offer [Last Updated On: October 21st, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 2nd, 2020]

- Saturday, 24th May 1913 Felder Charges Police Plot to Shield Slayer [Last Updated On: September 17th, 2023] [Originally Added On: September 21st, 2022]

- Saturday, 24th May 1913 Felders Fight is to Get Chief and Lanford Out of Office [Last Updated On: September 17th, 2023] [Originally Added On: September 15th, 2022]

- Saturday, 24th May 1913 Frame-Up Aimed at Burns Men, Says Tobie [Last Updated On: September 17th, 2023] [Originally Added On: September 18th, 2022]

- Saturday, 24th May 1913 Jones Attacks Beavers and Charges Police Crookedness [Last Updated On: September 19th, 2023] [Originally Added On: September 25th, 2022]

- Saturday, 24th May 1913 Mayor Admits Dictograph is Correct [Last Updated On: September 19th, 2023] [Originally Added On: September 24th, 2022]

- Saturday, 24th May 1913 Miles Says He Had Mayor Go to Room [Last Updated On: September 19th, 2023] [Originally Added On: September 22nd, 2022]

- Saturday, 24th May 1913 Plot on Life of Beavers Told by Colyar [Last Updated On: September 19th, 2023] [Originally Added On: September 23rd, 2022]

- Saturday, 24th May 1913 Strangulation Charge is in Indictments [Last Updated On: September 19th, 2023] [Originally Added On: September 19th, 2022]

- Sunday, 25th May 1913 Attorney, in Long Statement, Claims Dictograph Records Against Him Padded [Last Updated On: September 19th, 2023] [Originally Added On: September 13th, 2022]

- Sunday, 25th May 1913 Colyar Arrest Proper End to Plot of Crook [Last Updated On: September 19th, 2023] [Originally Added On: September 10th, 2022]

- Sunday, 25th May 1913 Colyar, Held as Forger, is Freed on Bond; Long Crime Record Charged [Last Updated On: September 19th, 2023] [Originally Added On: September 12th, 2022]

- Sunday, 25th May 1913 Dorsey to Present Graft Charges if They Stand Up [Last Updated On: September 19th, 2023] [Originally Added On: September 9th, 2022]

- Sunday, 25th May 1913 Ill Indict Gang, Says Beavers [Last Updated On: September 19th, 2023] [Originally Added On: September 14th, 2022]

- Sunday, 25th May 1913 Long Criminal Record of Colyar is Cited [Last Updated On: September 19th, 2023] [Originally Added On: September 11th, 2022]

- Monday, 26th May 1913 Accuses Tobie of Kidnaping Attempt [Last Updated On: September 19th, 2023] [Originally Added On: September 3rd, 2022]

- Monday, 26th May 1913 Evidence Against Frank Conclusive, Say Police [Last Updated On: September 19th, 2023] [Originally Added On: September 5th, 2022]

- Monday, 26th May 1913 Lay Bribery Effort to Franks Friends [Last Updated On: September 19th, 2023] [Originally Added On: September 7th, 2022]

- Monday, 26th May 1913 Mason Blocks Attempt to Oust Chief [Last Updated On: September 19th, 2023] [Originally Added On: September 1st, 2022]

- Monday, 26th May 1913 Mayor Eager to Bring Back Tenderloin, Declares Chief [Last Updated On: September 20th, 2023] [Originally Added On: September 6th, 2022]

- Monday, 26th May 1913 Mayor Gives Out Sizzling Reply to Chief Beavers [Last Updated On: September 20th, 2023] [Originally Added On: September 4th, 2022]

- Monday, 26th May 1913 Pinkerton Man Says Frank is Guilty [Last Updated On: September 20th, 2023] [Originally Added On: September 2nd, 2022]

- Monday, 26th May 1913 Will Take Charge of Graft to Grand Jury for Vindication [Last Updated On: September 20th, 2023] [Originally Added On: September 8th, 2022]

- Tuesday, 27th May 1913 Burns Man Quits Case; Declares He Is Opposed [Last Updated On: September 20th, 2023] [Originally Added On: August 30th, 2022]

- Tuesday, 27th May 1913 Felder Aide Offers Vice List to Chief [Last Updated On: September 20th, 2023] [Originally Added On: August 29th, 2022]

- Tuesday, 27th May 1913 State Faces Big Task in Trial of Frank as Slayer [Last Updated On: September 20th, 2023] [Originally Added On: August 28th, 2022]

- Tuesday, 27th May 1913 Suspicion Turned to Conley; Accused by Factory Foreman [Last Updated On: September 20th, 2023] [Originally Added On: August 31st, 2022]

- Wednesday, 28th May 1913 Chief Beavers to Renew His Vice War [Last Updated On: September 20th, 2023] [Originally Added On: August 24th, 2022]

- Wednesday, 28th May 1913 Conley Says Frank Took Him to Plant on Day of Slaying [Last Updated On: September 20th, 2023] [Originally Added On: August 27th, 2022]

- Wednesday, 28th May 1913 Conley Was in Factory on Day of Slaying [Last Updated On: September 21st, 2023] [Originally Added On: August 26th, 2022]

- Wednesday, 28th May 1913 Woman Writes in Defense of Leo M. Frank [Last Updated On: September 21st, 2023] [Originally Added On: August 25th, 2022]

- Thursday, 29th May 1913 Burns Joins in Hunt for Phagan Slayer [Last Updated On: September 21st, 2023] [Originally Added On: August 23rd, 2022]

- Thursday, 29th May 1913 Conley Re-enacts in Plant Part He Says He Took in Slaying [Last Updated On: September 21st, 2023] [Originally Added On: August 21st, 2022]

- Thursday, 29th May 1913 Felder Bribery Charge Expected [Last Updated On: September 21st, 2023] [Originally Added On: August 22nd, 2022]

- Thursday, 29th May 1913 Negro Conleys Affidavit Lays Bare Slaying [Last Updated On: September 22nd, 2023] [Originally Added On: August 20th, 2022]

- Thursday, 29th May 1913 Ready to Indict Conley as an Accomplice [Last Updated On: September 22nd, 2023] [Originally Added On: August 19th, 2022]

- Friday, 30th May 1913 Negro Conley Now Says He Helped to Carry Away Body [Last Updated On: September 22nd, 2023] [Originally Added On: August 18th, 2022]

- Saturday, 31st May 1913 Conley Star Actor in Dramatic Third Degree [Last Updated On: September 22nd, 2023] [Originally Added On: August 15th, 2022]

- Saturday, 31st May 1913 Plan to Confront Conley and Frank for New Admission [Last Updated On: September 22nd, 2023] [Originally Added On: August 16th, 2022]

- Saturday, 31st May 1913 Silence of Conley Put to End by Georgian [Last Updated On: September 23rd, 2023] [Originally Added On: August 17th, 2022]

- Saturday, 31st May 1913 Special Session of Grand Jury Called [Last Updated On: September 23rd, 2023] [Originally Added On: August 14th, 2022]

- Sunday, 1st June 1913 Confession of Conley Makes No Changes in States Case [Last Updated On: September 23rd, 2023] [Originally Added On: August 9th, 2022]

- Sunday, 1st June 1913 Conley is Unwittingly Friend of Frank, Says Old Police Reporter [Last Updated On: September 23rd, 2023] [Originally Added On: August 13th, 2022]

- Sunday, 1st June 1913 Conleys Story Cinches Case Against Frank, Says Lanford [Last Updated On: September 23rd, 2023] [Originally Added On: August 11th, 2022]

- Sunday, 1st June 1913 Dorseys Grill Fails to Make Conley Admit Hand in Killing [Last Updated On: September 24th, 2023] [Originally Added On: August 12th, 2022]

- Sunday, 1st June 1913 Today is Mary Phagans Birthday; Mother Tells of Party She Planned [Last Updated On: September 24th, 2023] [Originally Added On: August 10th, 2022]

- Monday, 2nd June 1913 5 to Testify Frank Was at Home at Hour Negro Says He Aided [Last Updated On: September 24th, 2023] [Originally Added On: August 8th, 2022]

- Monday, 2nd June 1913 Beavers to Talk Over the Felder Row With Dorsey [Last Updated On: September 24th, 2023] [Originally Added On: August 7th, 2022]

- Monday, 2nd June 1913 Negro Cook at Home Where Frank Lived Held by the Police [Last Updated On: September 24th, 2023] [Originally Added On: August 6th, 2022]

- Tuesday, the 3rd of June, 1913, Bitter Fight Certain in Trial of Leo Frank [Last Updated On: October 7th, 2023] [Originally Added On: August 4th, 2022]

- Tuesday, 3rd June 1913 Felder Says He Will Lay Bare Startling Police Graft Plans [Last Updated On: October 5th, 2023] [Originally Added On: August 5th, 2022]

- Wednesday, 4th June 1913 Cooks Sensational Affidavit [Last Updated On: October 5th, 2023] [Originally Added On: August 3rd, 2022]

- Wednesday, 4th June 1913 Fain Named in Vice Quiz as Resort Visitor [Last Updated On: October 5th, 2023] [Originally Added On: August 2nd, 2022]

- Wednesday, 4th June 1913 Franks Cook Was Counted Upon as Defense Witness [Last Updated On: October 5th, 2023] [Originally Added On: August 1st, 2022]

- Thursday, 5th June 1913 Challenges Felder to Prove His Charge [Last Updated On: October 6th, 2023] [Originally Added On: July 31st, 2022]

- Thursday, 5th June 1913 Cook Repudiates Entire Affidavit Police Possess [Last Updated On: October 6th, 2023] [Originally Added On: July 27th, 2022]

- Thursday, 5th June 1913 I Know My Husband is Innocent, Asserts Wife of Leo M. Frank [Last Updated On: October 6th, 2023] [Originally Added On: July 29th, 2022]

- Thursday, 5th June 1913 Mother Here to Aid Frank in Trial [Last Updated On: October 6th, 2023] [Originally Added On: July 30th, 2022]

- Thursday, 5th June 1913 New Conley Confession Reported to Jury [Last Updated On: October 6th, 2023] [Originally Added On: July 28th, 2022]

- Friday, 6th June 1913 Chief Says Law Balks His War on Vice [Last Updated On: October 7th, 2023] [Originally Added On: July 26th, 2022]

- Friday, 6th June 1913 Report Negro Found Who Saw Phagan Attack [Last Updated On: October 7th, 2023] [Originally Added On: July 25th, 2022]

- Saturday, 7th June 1913 Defense Bends Efforts to Prove Conley Slayer [Last Updated On: October 7th, 2023] [Originally Added On: July 22nd, 2022]

- Saturday, 7th June 1913 Defense Digs Deep to Show Conley is Phagan Girl Slayer [Last Updated On: October 7th, 2023] [Originally Added On: July 24th, 2022]

- Saturday, 7th June 1913 Mrs. Frank Attacks Solicitor H. M. Dorsey in a New Statement [Last Updated On: October 7th, 2023] [Originally Added On: July 23rd, 2022]

- Sunday, 8th June 1913 Fair Play Alone Can Find Truth in Phagan Puzzle, Declares Old Reporter [Last Updated On: October 8th, 2023] [Originally Added On: July 21st, 2022]

- Monday, 9th June 1913 Foreman Tells Why He Holds Conley Guilty [Last Updated On: October 8th, 2023] [Originally Added On: July 20th, 2022]

- Monday, 9th June 1913 Rosser Asks Grand Jury Grill for Conley [Last Updated On: October 8th, 2023] [Originally Added On: July 17th, 2022]

- Tuesday, 10th June 1913 Eyewitness to Phagan Slaying Sought [Last Updated On: October 8th, 2023] [Originally Added On: July 19th, 2022]

- Tuesday, 10th June 1913 Indictment of Felder and Fain Asked [Last Updated On: October 8th, 2023] [Originally Added On: July 18th, 2022]

- Wednesday, 11th June 1913 Asks Beavers to Investigate Affidavit [Last Updated On: October 9th, 2023] [Originally Added On: July 14th, 2022]

- Wednesday, 11th June 1913 Felder Returns Phagan Fund to Givers [Last Updated On: October 9th, 2023] [Originally Added On: July 16th, 2022]

- Wednesday, 11th June 1913 Plot Exposed, Says Felder, But Lanford Doubts Affidavit [Last Updated On: October 9th, 2023] [Originally Added On: July 13th, 2022]

- Wednesday, 11th June 1913 Police Hold Conley By Courts Order [Last Updated On: October 9th, 2023] [Originally Added On: July 15th, 2022]

- Thursday, 12th June 1913 Face Conley and Frank, Lanford Urges [Last Updated On: October 9th, 2023] [Originally Added On: July 12th, 2022]

- Friday, 13th June 1913 Judge Roan to Decide Conleys Jail Fate [Last Updated On: October 10th, 2023] [Originally Added On: July 9th, 2022]

- Friday, 13th June 1913 Negro Freed But Jailed Again On Suspicion [Last Updated On: October 10th, 2023] [Originally Added On: July 11th, 2022]

- Saturday, 14th June 1913 Sheriff Mangum Near End, Says Lawyer Smith [Last Updated On: October 10th, 2023] [Originally Added On: July 10th, 2022]

- Saturday, 14th June 1913 State Takes Advantage of Points Known [Last Updated On: October 10th, 2023] [Originally Added On: July 8th, 2022]

- Monday, 16th June 1913 Colyar Returns Promising Sensation [Last Updated On: October 10th, 2023] [Originally Added On: July 5th, 2022]

- Monday, 16th June 1913 Dorsey Aide Says Frank Is Fast In Net [Last Updated On: October 11th, 2023] [Originally Added On: July 6th, 2022]

- Tuesday, 17th June 1913 Sensations in Phagan Case at Hand [Last Updated On: October 11th, 2023] [Originally Added On: July 4th, 2022]

- Wednesday, 18th June 1913 Rush Plans for Trial of Leo Frank [Last Updated On: October 11th, 2023] [Originally Added On: July 7th, 2022]

- Thursday, 19th June 1913 Blow Aimed at Formby Story [Last Updated On: October 11th, 2023] [Originally Added On: July 3rd, 2022]

- Friday, 20th June 1913 Frank Trial Will Not Be Long One [Last Updated On: October 11th, 2023] [Originally Added On: July 2nd, 2022]

- Saturday, 21st June 1913 Justice Aim in Phagan Case, Says Hooper [Last Updated On: October 12th, 2023] [Originally Added On: July 1st, 2022]

- Sunday, 22nd June 1913 Arnold to Aid Frank [Last Updated On: October 12th, 2023] [Originally Added On: June 30th, 2022]

- Sunday, 22nd June 1913 Jurors, Not Newspapers, To Return Frank Verdict, Declares Old Reporter [Last Updated On: October 12th, 2023] [Originally Added On: June 29th, 2022]

- Monday, 23rd June 1913 State Ready for Frank Trial on June 30 [Last Updated On: October 12th, 2023] [Originally Added On: June 28th, 2022]

- Monday, 23rd June 1913 Venire of 72 for Frank Jury Is Drawn [Last Updated On: October 12th, 2023] [Originally Added On: June 27th, 2022]

- Tuesday, 24th June 1913 Both Sides Called in Conference by Judge; Trial Set for July 28 [Last Updated On: October 13th, 2023] [Originally Added On: June 26th, 2022]

- Wednesday, 25th June 1913 Conley, Put on Grill, Sticks Story [Last Updated On: October 13th, 2023] [Originally Added On: June 25th, 2022]

- Thursday, 26th June 1913 Stover Girl Will Star in Frank Trial [Last Updated On: October 13th, 2023] [Originally Added On: June 24th, 2022]

- Friday, 27th June 1913 Lanford and Felder Are Held for Libel [Last Updated On: October 13th, 2023] [Originally Added On: June 23rd, 2022]

- Friday, 27th June 1913 New Frank Evidence Held by Dorsey [Last Updated On: October 13th, 2023] [Originally Added On: June 22nd, 2022]

- Saturday, 28th June 1913 Gov. Slaton Takes Oath Simply [Last Updated On: October 14th, 2023] [Originally Added On: June 20th, 2022]

- Saturday, 28th June 1913 State Secures New Phagan Evidence [Last Updated On: October 14th, 2023] [Originally Added On: June 21st, 2022]

- Sunday, 29th June 1913 Brilliant Legal Battle Is Sure as Hooper And Arnold Clash in Trial of Leo Frank [Last Updated On: October 14th, 2023] [Originally Added On: June 18th, 2022]

- Sunday, 29th June 1913 Many Experts to Take Stand in Frank Trial [Last Updated On: October 14th, 2023] [Originally Added On: June 19th, 2022]

- Monday, 30th June 1913 Conley Tale Is Hope of Defense [Last Updated On: October 14th, 2023] [Originally Added On: June 17th, 2022]

- Tuesday, 1st July 1913 Colyar Indicted as Libeler of Col. Felder [Last Updated On: October 15th, 2023] [Originally Added On: June 13th, 2022]

- Tuesday, 1st July 1913 Colyar Not Indicted On Charge of Libel [Last Updated On: October 15th, 2023] [Originally Added On: June 15th, 2022]

- Tuesday, 1st July 1913 Frank Is Willing for State to Grill Him [Last Updated On: October 15th, 2023] [Originally Added On: June 12th, 2022]

- Tuesday, 1st July 1913 May Indict Conley as Slayer [Last Updated On: October 15th, 2023] [Originally Added On: June 16th, 2022]

- Tuesday, 1st July 1913 May Indict Conley in Phagan Case [Last Updated On: October 15th, 2023] [Originally Added On: June 14th, 2022]

- Tuesday, 1st July 1913 “No” Bill Is Returned Against A. S. Colyar [Last Updated On: October 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: June 11th, 2022]

- Wednesday, 2nd July 1913 Findings in Probe are Guarded [Last Updated On: October 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: June 10th, 2022]

- Thursday, 3rd July 1913 Attempt by Colyar To Disbar Felder Is Halted; Tries Again [Last Updated On: October 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: June 9th, 2022]

- Thursday, 3rd July 1913 Writ Sought In Move to Free Negro Lee [Last Updated On: October 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: June 8th, 2022]

- Friday, 4th July 1913 New Testimony Lays Crime to Conley [Last Updated On: October 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: June 7th, 2022]

- Saturday, 5th July 1913 Application for Lee’s Release Delayed [Last Updated On: October 17th, 2023] [Originally Added On: June 5th, 2022]

- Saturday, 5th July 1913 Drop Ninth in Police Scandal [Last Updated On: October 17th, 2023] [Originally Added On: June 6th, 2022]

- Saturday, 5th July 1913 Liberty for Newt Lee Sought [Last Updated On: October 17th, 2023] [Originally Added On: June 3rd, 2022]

- Saturday, 5th July 1913 Unbiased in the Flanders Case, Says Slaton [Last Updated On: October 17th, 2023] [Originally Added On: June 4th, 2022]

- Sunday, 6th July 1913 Application to Release Lee is Ready to File [Last Updated On: October 17th, 2023] [Originally Added On: June 1st, 2022]

- Sunday, 6th July 1913 New Move in Phagan Case by Solicitor [Last Updated On: October 18th, 2023] [Originally Added On: May 31st, 2022]

- Sunday, 6th July 1913 Phagan Case Centers on Conley; Negro Lone Hope of Both Sides [Last Updated On: October 18th, 2023] [Originally Added On: June 2nd, 2022]

- Monday, 7th July 1913 Lee’s Attorney is Ready for Writ Fight [Last Updated On: October 18th, 2023] [Originally Added On: May 30th, 2022]

- Monday, 7th July 1913 Operations of Slavers in Hotels Bared [Last Updated On: October 18th, 2023] [Originally Added On: May 29th, 2022]

- Tuesday, 8th July 1913 Attitude of Defense Secret [Last Updated On: October 18th, 2023] [Originally Added On: May 24th, 2022]

- Tuesday, 8th July 1913 Girl Tells of Life in Slavers’ Hands [Last Updated On: October 19th, 2023] [Originally Added On: May 23rd, 2022]

- Tuesday, 8th July 1913 Grants Right to Demand Lee’s Freedom [Last Updated On: October 19th, 2023] [Originally Added On: May 27th, 2022]

- Tuesday, 8th July 1913 Police Hunt Principals in Expose [Last Updated On: October 19th, 2023] [Originally Added On: May 28th, 2022]

- Tuesday, 8th July 1913 Refused by Brown, Mangham Now Asks Slaton for Pardon [Last Updated On: October 19th, 2023] [Originally Added On: May 25th, 2022]

- Tuesday, 8th July 1913 State Sure Lee Will Not Be Released [Last Updated On: October 19th, 2023] [Originally Added On: May 26th, 2022]

- Wednesday, 9th July 1913 Girl Springs Sensation in Phagan Case [Last Updated On: October 20th, 2023] [Originally Added On: May 22nd, 2022]

- Wednesday, 9th July 1913 New Evidence in Phagan Case Found [Last Updated On: October 20th, 2023] [Originally Added On: May 21st, 2022]

- Wednesday, 9th July 1913 Sensations in Story of Girl Victim [Last Updated On: October 20th, 2023] [Originally Added On: May 20th, 2022]

- Thursday, 10th July 1913 Beavers in Speech Warns Policemen to Keep Out of Dives [Last Updated On: October 20th, 2023] [Originally Added On: May 17th, 2022]

- Thursday, 10th July 1913 Beavers’ War on Vice is Lauded by Women [Last Updated On: October 20th, 2023] [Originally Added On: May 16th, 2022]

- Thursday, 10th July 1913 Chief Expects Arrests in Vice Probe [Last Updated On: October 21st, 2023] [Originally Added On: May 19th, 2022]

- Thursday, 10th July 1913 Says Conley Confessed Slaying [Last Updated On: October 22nd, 2023] [Originally Added On: May 18th, 2022]

- Friday, 11th July 1913 Girl Tells Police Startling Story of Vice Ring [Last Updated On: October 21st, 2023] [Originally Added On: May 14th, 2022]

- Friday, 11th July 1913 Mincey’s Story Jolts Police to Activity [Last Updated On: October 21st, 2023] [Originally Added On: May 13th, 2022]

- Friday, 11th July 1913 Slaying Charge for Conley Is Expected [Last Updated On: October 21st, 2023] [Originally Added On: May 15th, 2022]

- Saturday, 12th July 1913 Conley Kept on Grill 4 Hours [Last Updated On: October 22nd, 2023] [Originally Added On: May 8th, 2022]

- Saturday, 12th July 1913 Dragnet for ‘Slavers’ Is Set [Last Updated On: October 22nd, 2023] [Originally Added On: May 9th, 2022]

- Saturday, 12th July 1913 Five Caught in Beavers’ Vice Net [Last Updated On: October 22nd, 2023] [Originally Added On: May 10th, 2022]

- Saturday, 12th July 1913 Parents Are Blamed for ‘Slavery’ [Last Updated On: October 22nd, 2023] [Originally Added On: May 11th, 2022]

- Saturday, 12th July 1913 Says Women Heard Conley Confession [Last Updated On: October 22nd, 2023] [Originally Added On: May 12th, 2022]

- Sunday, 13th July 1913 Affidavits to Back Mincey Story Found [Last Updated On: October 23rd, 2023] [Originally Added On: May 7th, 2022]

- Sunday, 13th July 1913 Indictment of Conley Puzzle for Grand Jury [Last Updated On: October 23rd, 2023] [Originally Added On: May 5th, 2022]

- Sunday, 13th July 1913 Seek Negro Who Says He Was Eye-Witness to Phagan Murder [Last Updated On: October 23rd, 2023] [Originally Added On: May 6th, 2022]

- Monday, 14th July 1913 Girl Bares New Vice System [Last Updated On: October 23rd, 2023] [Originally Added On: May 2nd, 2022]

- Monday, 14th July 1913 Mincey’s Own Story [Last Updated On: October 23rd, 2023] [Originally Added On: May 1st, 2022]

- Monday, 14th July 1913 Prosecution Attacks Mincey’s Affidavit [Last Updated On: October 24th, 2023] [Originally Added On: May 4th, 2022]

- Monday, 14th July 1913 Vice Pickets Posted at Hotels [Last Updated On: October 24th, 2023] [Originally Added On: May 3rd, 2022]

- Tuesday, 15th July 1913 Holloway Corroborates Mincey’s Affidavit [Last Updated On: October 24th, 2023] [Originally Added On: April 28th, 2022]

- Tuesday, 15th July 1913 Police Close 2 Rooming Houses [Last Updated On: October 24th, 2023] [Originally Added On: April 30th, 2022]

- Tuesday, 15th July 1913 White Men Fined in War on Negro Dives [Last Updated On: October 24th, 2023] [Originally Added On: April 29th, 2022]

- Tuesday, 15th July 1913 Woodward Aids Chief in Vice Crusade [Last Updated On: October 25th, 2023] [Originally Added On: April 27th, 2022]

- Wednesday, 16th July 1913 Dorsey Adds Startling Evidence [Last Updated On: October 25th, 2023] [Originally Added On: April 26th, 2022]

- Wednesday, 16th July 1913 State to Fight Move to Indict Jim Conley [Last Updated On: October 25th, 2023] [Originally Added On: April 25th, 2022]

- Thursday, 17th July 1913 Dorsey Blocked Indictment of Conley [Last Updated On: October 25th, 2023] [Originally Added On: April 24th, 2022]

- Thursday, 17th July 1913 Mayor and Broyles in War of Words [Last Updated On: October 25th, 2023] [Originally Added On: April 23rd, 2022]

- Thursday, 17th July 1913 Mayor Asked to Probe Action of Police [Last Updated On: October 26th, 2023] [Originally Added On: April 21st, 2022]

- Thursday, 17th July 1913 Woodward Enemy to Society, Says Recorder Broyles [Last Updated On: October 26th, 2023] [Originally Added On: April 20th, 2022]

- Thursday, 17th July 1913 Youth Accused in Vice Ring on Trial [Last Updated On: October 26th, 2023] [Originally Added On: April 22nd, 2022]

- Friday, 18th July 1913 Detectives Working to Discredit Mincey [Last Updated On: October 26th, 2023] [Originally Added On: April 19th, 2022]

- Friday, 18th July 1913 Woodward-Broyles Breach Widens [Last Updated On: October 26th, 2023] [Originally Added On: April 18th, 2022]

- Saturday, 19th July 1913 Dorsey Resists Move to Indict Jim Conley [Last Updated On: October 26th, 2023] [Originally Added On: April 17th, 2022]

- Saturday, 19th July 1913 Natural Crank, Mayor’s Shot at Broyles [Last Updated On: October 26th, 2023] [Originally Added On: April 16th, 2022]

- Sunday, 20th July 1913 Attorney for Conley Makes a Statement [Last Updated On: October 26th, 2023] [Originally Added On: April 12th, 2022]

- Sunday, 20th July 1913 Counsel of Frank Says Dorsey Has Sought to Hide Facts [Last Updated On: October 26th, 2023] [Originally Added On: April 15th, 2022]

- Sunday, 20th July 1913 Dorsey Fights Movement to Indict Conley [Last Updated On: October 26th, 2023] [Originally Added On: April 11th, 2022]

- Sunday, 20th July 1913 Mincey Ready to Tell Story to Grand Jury [Last Updated On: October 26th, 2023] [Originally Added On: April 13th, 2022]

- Sunday, 20th July 1913 Mincey Story Declared Vital To Both Sides in Frank Case [Last Updated On: October 26th, 2023] [Originally Added On: April 14th, 2022]

- Monday, 21st July 1913 Doctor And Girl Are Taken On Vice Charge [Last Updated On: October 26th, 2023] [Originally Added On: April 8th, 2022]

- Monday, 21st July 1913 Four Women Caught In Vice Net Escape From Martha Home [Last Updated On: October 26th, 2023] [Originally Added On: April 10th, 2022]

- Monday, 21st July 1913 Grand Jury Meets to Consider Conley Case [Last Updated On: October 26th, 2023] [Originally Added On: April 7th, 2022]

- Monday, 21st July 1913 Protest of Solicitor Dorsey Wins [Last Updated On: October 27th, 2023] [Originally Added On: April 9th, 2022]

- Tuesday, 22nd July 1913 Defense Asks Ruling on Delaying Frank Trial [Last Updated On: October 27th, 2023] [Originally Added On: April 6th, 2022]

- Tuesday, 22nd July 1913 Grand Jury Defers Action on Conley [Last Updated On: October 27th, 2023] [Originally Added On: April 5th, 2022]

- Tuesday, 22nd July 1913 Story of Phagan Case by Chapters [Last Updated On: October 27th, 2023] [Originally Added On: April 4th, 2022]

- Wednesday, 23rd July 1913 Conley is Confronted with Lee Dorsey Grills Negroes in Same Cell at Jail [Last Updated On: October 27th, 2023] [Originally Added On: April 3rd, 2022]

- Wednesday, 23rd July 1913 Lanford Ridicules Bludgeon Evidence [Last Updated On: October 27th, 2023] [Originally Added On: April 1st, 2022]

- Wednesday, 23rd July 1913 Second Chapter in Phagan Mystery [Last Updated On: October 27th, 2023] [Originally Added On: April 2nd, 2022]

- Thursday, 24th July 1913 Frank Trial Delay up to Roan [Last Updated On: October 27th, 2023] [Originally Added On: March 28th, 2022]

- Thursday, 24th July 1913 Let the Frank Trial Go On [Last Updated On: October 27th, 2023] [Originally Added On: March 31st, 2022]

- Thursday, 24th July 1913 Third Chapter in Phagan Mystery [Last Updated On: October 27th, 2023] [Originally Added On: March 29th, 2022]

- Thursday, 24th July 1913 Veneir is Drawn to Try Leo M. Frank Monday [Last Updated On: October 28th, 2023] [Originally Added On: March 30th, 2022]

- Friday, 25th July 1913 Witnesses for Frank Called [Last Updated On: October 28th, 2023] [Originally Added On: March 27th, 2022]

- Saturday, 26th July 1913 Chapter 5 in Phagan Case [Last Updated On: October 28th, 2023] [Originally Added On: March 24th, 2022]

- Saturday, 26th July 1913 Pinkerton Chief Scored by Lanford [Last Updated On: October 28th, 2023] [Originally Added On: March 26th, 2022]

- Saturday, 26th July 1913 Present New Evidence Against Frank [Last Updated On: October 28th, 2023] [Originally Added On: March 25th, 2022]

- Sunday, 27th July 1913 Brewster Denies Aiding Dorsey in Phagan Case [Last Updated On: October 28th, 2023] [Originally Added On: March 12th, 2022]

- Sunday, 27th July 1913 Defense Claims Conley and Lee Prepared Notes [Last Updated On: October 28th, 2023] [Originally Added On: March 18th, 2022]

- Sunday, 27th July 1913 Every Bit of Evidence Against Frank Sifted and Tested, Declares Solicitor [Last Updated On: October 28th, 2023] [Originally Added On: March 19th, 2022]

- Sunday, 27th July 1913 Frank Fights for Life Monday [Last Updated On: October 28th, 2023] [Originally Added On: March 22nd, 2022]

- Sunday, 27th July 1913 Frank Watches Closely as the Men Who are to Decide Fate are Picked [Last Updated On: October 28th, 2023] [Originally Added On: March 13th, 2022]

- Sunday, 27th July 1913 Phagan Case of Peculiar And Enthralling Interest [Last Updated On: October 29th, 2023] [Originally Added On: March 16th, 2022]

- Sunday, 27th July 1913 Pinkerton Men Brand Lanford Charges False [Last Updated On: October 29th, 2023] [Originally Added On: March 23rd, 2022]

- Sunday, 27th July 1913 Prominent Atlantans Named On Frank Trial Jury Venire [Last Updated On: October 29th, 2023] [Originally Added On: March 20th, 2022]

- Sunday, 27th July 1913 Public Demands Frank Trial To-morrow [Last Updated On: October 29th, 2023] [Originally Added On: March 17th, 2022]

- Sunday, 27th July 1913 State Bolsters Conley [Last Updated On: October 29th, 2023] [Originally Added On: March 21st, 2022]

- Sunday, 27th July 1913 Trial to Surpass in Interest Any in Fulton County History [Last Updated On: October 29th, 2023] [Originally Added On: March 15th, 2022]

- Sunday, 27th July 1913 Venire Whipped Into Shape Rapidly; Negro Is Eligible [Last Updated On: October 29th, 2023] [Originally Added On: March 11th, 2022]

- Sunday, 27th July 1913 Work of Choosing Jury for Trial of Frank Difficult [Last Updated On: October 29th, 2023] [Originally Added On: March 14th, 2022]

- Monday, 28th July 1913 Frank, Feeling Tiptop, Smiling and Confident, is Up Long Before Trial [Last Updated On: October 29th, 2023] [Originally Added On: March 9th, 2022]

- Monday, 28th July 1913 Frank Jury [Last Updated On: October 29th, 2023] [Originally Added On: March 7th, 2022]

- Monday, 28th July 1913 Jury Complete to Try Frank [Last Updated On: October 30th, 2023] [Originally Added On: March 10th, 2022]

- Monday, 28th July 1913 Mary Phagan’s Mother Testifies [Last Updated On: October 30th, 2023] [Originally Added On: March 8th, 2022]

- Tuesday, 29th July 1913 After Rosser’s Fierce Grilling All Negro, Newt Lee, Asked for Was Chew or Bacca-AnyKind [Last Updated On: October 30th, 2023] [Originally Added On: March 3rd, 2022]

- Tuesday, 29th July 1913 Defense Wins Point After Fierce Lawyers’ Clash [Last Updated On: October 30th, 2023] [Originally Added On: March 6th, 2022]

- Tuesday, 29th July 1913 Lee’s Quaint Answers Rob Leo Frank’s Trial of All Signs of Rancor [Last Updated On: October 30th, 2023] [Originally Added On: March 5th, 2022]

- Tuesday, 29th July 1913 Tragedy, Ages Old, Lurks in Commonplace Court Setting [Last Updated On: October 30th, 2023] [Originally Added On: March 4th, 2022]

- Wednesday, 30th July 1913 Defense Plans Sensation, Line of Queries Indicates [Last Updated On: October 30th, 2023] [Originally Added On: February 26th, 2022]

- Wednesday, 30th July 1913 Flashes of Tragedy Pierce Legal Tilts at Frank Trial [Last Updated On: October 30th, 2023] [Originally Added On: February 28th, 2022]

- Wednesday, 30th July 1913 Frank’s Mother Pitiful Figure of the Trial [Last Updated On: October 30th, 2023] [Originally Added On: February 27th, 2022]

- Wednesday, 30th July 1913 Gantt Has Startling Evidence; Dorsey Promises New Testimony Against Frank [Last Updated On: October 30th, 2023] [Originally Added On: March 2nd, 2022]

- Wednesday, 30th July 1913 Rosser’s Examination of Lee Just a Shot in Dark; Hoped to Start Quarry [Last Updated On: October 31st, 2023] [Originally Added On: March 1st, 2022]

- Thursday, 31st July 1913 Collapse of Testimony of Black and Hix Girl’s Story Big Aid to Frank [Last Updated On: October 31st, 2023] [Originally Added On: February 24th, 2022]

- Thursday, 31st July 1913 Crimson Trail Leads Crowd to Courtroom Sidewalk [Last Updated On: October 31st, 2023] [Originally Added On: February 22nd, 2022]

- Thursday, 31st July 1913 Holloway Accused by Solicitor Dorsey of Entrapping State [Last Updated On: October 31st, 2023] [Originally Added On: February 21st, 2022]

- Thursday, 31st July 1913 Red Bandanna, a Jackknife and Plennie Minor Preserve Order [Last Updated On: October 31st, 2023] [Originally Added On: February 20th, 2022]

- Thursday, 31st July 1913 Scott Trapped Us, Dorsey Charges; Pinkerton Man Is Also Attacked by the Defense [Last Updated On: October 31st, 2023] [Originally Added On: February 25th, 2022]

- Thursday, 31st July 1913 State Balloon Soars When Dorsey, Roiled, Cries ‘Plant’ [Last Updated On: October 31st, 2023] [Originally Added On: February 23rd, 2022]

- Friday, 1st August 1913 Conley Takes Stand Saturday [Last Updated On: October 31st, 2023] [Originally Added On: February 19th, 2022]

- Friday, 1st August 1913 Defense Not Helped by Witnesses Accused of Entrapping the State [Last Updated On: October 31st, 2023] [Originally Added On: February 17th, 2022]

- Friday, 1st August 1913 Dorsey Unafraid as He Faces Champions of the Atlanta Bar [Last Updated On: October 31st, 2023] [Originally Added On: February 16th, 2022]

- Friday, 1st August 1913 Girl Slain After Frank Left Factory, Believed to be Defense Theory [Last Updated On: November 1st, 2023] [Originally Added On: February 15th, 2022]

- Friday, 1st August 1913 Sherlocks, Lupins and Lecoqs See Frank Trial [Last Updated On: November 1st, 2023] [Originally Added On: February 18th, 2022]

- Saturday, 2nd August 1913 Defense Threatens a Mistrial [Last Updated On: November 1st, 2023] [Originally Added On: February 14th, 2022]

- Saturday, 2nd August 1913 Frank Juror’s Life One Grand, Sweet SongNot [Last Updated On: November 1st, 2023] [Originally Added On: February 10th, 2022]

- Saturday, 2nd August 1913 Roan Holding Scales of Justice With Steady Hand [Last Updated On: November 1st, 2023] [Originally Added On: February 11th, 2022]

- Saturday, 2nd August 1913 State Hopes Dr. Harris Fixed Fact That Frank Had Chance to Kill Girl [Last Updated On: November 2nd, 2023] [Originally Added On: February 12th, 2022]

- Saturday, 2nd August 1913 Will 5 Ounces of Cabbage Help Convict Leo M. Frank? [Last Updated On: November 2nd, 2023] [Originally Added On: February 13th, 2022]

- Sunday, 3rd August 1913 Conley to Bring Frank Case Crisis [Last Updated On: November 2nd, 2023] [Originally Added On: February 8th, 2022]

- Sunday, 3rd August 1913 First Week of Frank Trial Ends With Both Sides Sure of Victory [Last Updated On: November 2nd, 2023] [Originally Added On: February 9th, 2022]

- Sunday, 3rd August 1913 Leo Frank’s Eyes Show Intense Interest in Every Phase of Case [Last Updated On: November 2nd, 2023] [Originally Added On: February 7th, 2022]

- Monday, 4th August 1913 Boiled Cabbage Brings Hypothetical Question Stage in Frank’s Trial [Last Updated On: November 3rd, 2023] [Originally Added On: February 3rd, 2022]

- Monday, 4th August 1913 Conley’s Story In Detail; Women Barred By Judge [Last Updated On: November 3rd, 2023] [Originally Added On: February 5th, 2022]

- Monday, 4th August 1913 Dorsey Tries to Prove Frank Had Chance to Kill Girl [Last Updated On: November 3rd, 2023] [Originally Added On: January 28th, 2022]

- Monday, 4th August 1913 Dramatic Moment of Trial Comes as Negro Takes Stand [Last Updated On: November 3rd, 2023] [Originally Added On: January 29th, 2022]

- Monday, 4th August 1913 Envy Not the Juror! His Lot, Mostly, Is Monotony [Last Updated On: November 3rd, 2023] [Originally Added On: February 2nd, 2022]

- Monday, 4th August 1913 Frank Calm and Jurors Tense While Jim Conley Tells His Ghastly Tale [Last Updated On: November 4th, 2023] [Originally Added On: January 30th, 2022]

- Monday, 4th August 1913 Frank Witness Nearly Killed By a Mad Dog [Last Updated On: November 4th, 2023] [Originally Added On: February 1st, 2022]

- Monday, 4th August 1913 Jim Conley’s Story as Matter of Fact as if it Were of His Day’s Work [Last Updated On: November 4th, 2023] [Originally Added On: February 4th, 2022]

- Monday, 4th August 1913 Jurors Strain Forward to Catch Conley Story; Frank’s Interest Mild [Last Updated On: November 4th, 2023] [Originally Added On: January 31st, 2022]

- Monday, 4th August 1913 Ordeal is Borne with Reserve by Franks [Last Updated On: November 4th, 2023] [Originally Added On: January 27th, 2022]

- Monday, 4th August 1913 Rosser’s Grilling of Negro Leads to Hot Clashes by Lawyers [Last Updated On: November 5th, 2023] [Originally Added On: February 6th, 2022]

- Tuesday, 5th August 1913 Conleys Charge Turns Frank Trial Into Fight To Worse Than Death [Last Updated On: November 5th, 2023] [Originally Added On: January 25th, 2022]

- Tuesday, 5th August 1913 Many Discrepancies To Be Bridged in Conleys Stories [Last Updated On: November 5th, 2023] [Originally Added On: January 23rd, 2022]

- Tuesday, 5th August 1913 Mrs. Frank Breaks Down in Court [Last Updated On: November 5th, 2023] [Originally Added On: January 26th, 2022]

- Tuesday, 5th August 1913 Rosser Goes Fiercely After Jim Conley [Last Updated On: November 5th, 2023] [Originally Added On: January 22nd, 2022]

- Tuesday, 5th August 1913 Traditions of the South Upset; White Mans Life Hangs on Negros Word [Last Updated On: November 6th, 2023] [Originally Added On: January 24th, 2022]

- Wednesday, 6th August 1913 Accuser of Conley is Ready to Testify [Last Updated On: November 6th, 2023] [Originally Added On: January 19th, 2022]

- Wednesday, 6th August 1913 Can Jury Obey if Told to Forget Base Charge? [Last Updated On: November 6th, 2023] [Originally Added On: January 21st, 2022]

- Wednesday, 6th August 1913 Conley Swears Frank Hid Purse [Last Updated On: November 6th, 2023] [Originally Added On: January 20th, 2022]

- Wednesday, 6th August 1913 Crowd Set in Its Opinions [Last Updated On: November 6th, 2023] [Originally Added On: January 18th, 2022]

- Wednesday, 6th August 1913 Dorsey Accomplishes Aim Despite Big Odds [Last Updated On: November 7th, 2023] [Originally Added On: January 17th, 2022]

- Wednesday, 6th August 1913 Judge Will Rule on Evidence Attacked by Defense at 2 P.M. [Last Updated On: November 7th, 2023] [Originally Added On: January 16th, 2022]

- Thursday, 7th August 1913 Jim Conley, the Ebony Chevalier of Crime, is Darktowns Own Hero [Last Updated On: November 7th, 2023] [Originally Added On: January 14th, 2022]

- Thursday, 7th August 1913 Roans Ruling Heavy Blow to Defense [Last Updated On: November 7th, 2023] [Originally Added On: January 12th, 2022]

- Thursday, 7th August 1913 State Ends Case Against Frank [Last Updated On: November 7th, 2023] [Originally Added On: January 15th, 2022]

- Thursday, 7th August 1913 Trial as Varied as Vaudeville Exhibition [Last Updated On: November 8th, 2023] [Originally Added On: January 13th, 2022]

- Thursday, 7th August 1913 Trial Experts Conflict on Time of Girls Death [Last Updated On: November 8th, 2023] [Originally Added On: January 11th, 2022]

- Friday, 8th August 1913 Scott Put Conleys Story in Strange Light [Last Updated On: November 8th, 2023] [Originally Added On: January 8th, 2022]

- Friday, 8th August 1913 State, Tied by Conleys Story, Now Must Stand Still Under Hot Fire [Last Updated On: November 8th, 2023] [Originally Added On: January 9th, 2022]

- Friday, 8th August 1913 Witnesses Attack Conley Story [Last Updated On: November 9th, 2023] [Originally Added On: January 10th, 2022]

- Saturday, 9th August 1913 Absence of Alienists and the Hypothetical Question Distinguishes Frank Trial [Last Updated On: November 9th, 2023] [Originally Added On: January 5th, 2022]

- Saturday, 9th August 1913 Confusion of Holloway Spoils Close of Good Day for the Defense [Last Updated On: November 9th, 2023] [Originally Added On: January 3rd, 2022]

- Saturday, 9th August 1913 Daltons Testimony False, Girl Named on Stand Says [Last Updated On: November 9th, 2023] [Originally Added On: January 6th, 2022]

- Saturday, 9th August 1913 Exposure of Conley Story Time Flaws is Sought by Defense [Last Updated On: November 9th, 2023] [Originally Added On: January 1st, 2022]

- Saturday, 9th August 1913 Heres the Time Clock Puzzle in Frank Trial; Can You Figure It Out? [Last Updated On: October 13th, 2024] [Originally Added On: January 4th, 2022]

- Saturday, 9th August 1913 State Attacks Frank Report [Last Updated On: January 2nd, 2022] [Originally Added On: January 2nd, 2022]

- Sunday, 10th August 1913 Case Never is Discussed by Frank Jurors [Last Updated On: April 26th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 28th, 2021]

- Sunday, 10th August 1913 Conley, Unconcerned, Asks Nothing of Trial [Last Updated On: December 27th, 2021] [Originally Added On: December 27th, 2021]

- Sunday, 10th August 1913 Dalton Sticks Firmly To Story Told on Stand [Last Updated On: April 26th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 24th, 2021]

- Sunday, 10th August 1913 Frank or Conley? Still Question [Last Updated On: November 11th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 31st, 2021]

- Sunday, 10th August 1913 Frank Struggles to Prove His Conduct Was Blameless [Last Updated On: November 11th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 29th, 2021]

- Sunday, 10th August 1913 Interest in Trial Now Centers in Story of Mincey [Last Updated On: November 11th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 26th, 2021]

- Sunday, 10th August 1913 Mary Phagans Mother to be Spared at Trial [Last Updated On: November 11th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 23rd, 2021]

- Sunday, 10th August 1913 One Glance at Conley Boosts Darwin Theory [Last Updated On: November 11th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 22nd, 2021]

- Sunday, 10th August 1913 Phagan Trial Makes Eleven Widows But Jurors Wives Are Peeresses Also [Last Updated On: November 12th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 25th, 2021]

- Sunday, 10th August 1913 Study of Frank Convicts, Then It Turns and Acquits [Last Updated On: November 12th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 30th, 2021]

- Monday, 11th August 1913 Defense Bitterly Attacks Harris [Last Updated On: November 12th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 21st, 2021]

- Monday, 11th August 1913 Deputy Hunting Scalp Of Juror-Ventiloquist [Last Updated On: November 12th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 20th, 2021]

- Monday, 11th August 1913 Grief-Stricken Mother Shows No Vengefulness [Last Updated On: November 12th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 19th, 2021]

- Monday, 11th August 1913 Interest Unabated as Dramatic Frank Trial Enters Third Week [Last Updated On: November 13th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 18th, 2021]

- Tuesday, 12th August 1913 Attacks on Dr. Harris Give Defense Good Day [Last Updated On: November 13th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 15th, 2021]

- Tuesday, 12th August 1913 Frank Trial Witness is Sure, At Least, of One Thinga Good Ragging [Last Updated On: November 13th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 16th, 2021]

- Tuesday, 12th August 1913 Peoples Cry for Justice Is Proof Sentiment Still Lives [Last Updated On: November 13th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 14th, 2021]

- Tuesday, 12th August 1913 State Charges Premeditated Crime [Last Updated On: November 13th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 17th, 2021]

- Wednesday, 13th August 1913 Both Sides Aim for Justice in the Trial of Frank [Last Updated On: November 14th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 12th, 2021]

- Wednesday, 13th August 1913 Franks Mother Stirs Courtroom [Last Updated On: November 14th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 13th, 2021]

- Wednesday, 13th August 1913 State Calls More Witnesses; Defense Builds Up an Alibi [Last Updated On: November 14th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 11th, 2021]

- Thursday, 14th August 1913 Defense Slips Load by Putting up Character of Leo Frank as Issue [Last Updated On: November 14th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 8th, 2021]

- Thursday, 14th August 1913 State Fights Franks Alibi [Last Updated On: November 14th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 6th, 2021]

- Thursday, 14th August 1913 State Wants Wife and Mother Excluded [Last Updated On: November 15th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 10th, 2021]

- Thursday, 14th August 1913 States Sole Aim is to Convict, Defenses to Clear in Modern Trial [Last Updated On: November 15th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 9th, 2021]

- Thursday, 14th August 1913 Steel Workers Enthralled by Leo Frank Trial [Last Updated On: November 15th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 7th, 2021]

- Friday, 15th August 1913 Frank Prepares to Take Stand [Last Updated On: July 17th, 2023] [Originally Added On: May 22nd, 2023]

- Friday, 15th August 1913 Testimony of Girls Help to Leo M. Frank [Last Updated On: July 17th, 2023] [Originally Added On: May 20th, 2023]

- Friday, 15th August 1913 What They Say Wont Hurt Leo Frank; State Must Prove Depravity [Last Updated On: July 17th, 2023] [Originally Added On: May 21st, 2023]

- Saturday, 16th August 1913 Girls Testify For and Against Frank [Last Updated On: July 17th, 2023] [Originally Added On: May 19th, 2023]

- Saturday, 16th August 1913 Many Testify to Franks Good Character [Last Updated On: July 17th, 2023] [Originally Added On: May 17th, 2023]

- Saturday, 16th August 1913 Mothers Love Gives Trial Its Great Scene [Last Updated On: July 17th, 2023] [Originally Added On: May 16th, 2023]

- Saturday, 16th August 1913 Statement by Frank Will Be the Climactic Feature of the Trial [Last Updated On: July 17th, 2023] [Originally Added On: May 18th, 2023]

- Sunday, 17th August 1913 Supreme Test Comes As State Trains Guns On Frank's Character [Last Updated On: August 30th, 2023] [Originally Added On: August 11th, 2023]

- Monday, 18th August 1913 Leo Frank Testifies [Last Updated On: February 17th, 2024] [Originally Added On: September 2nd, 2023]

- Tuesday, 19th August 1913 Jim Conley To Be Recalled [Last Updated On: February 17th, 2024] [Originally Added On: September 12th, 2023]

- Wednesday, 20th August 1913 State Closes Frank Case Near Jury Defense Begins Its Sur-rubettual. Hopes To Conclude Quickly [Last Updated On: November 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: August 29th, 2023]

- Thursday, 21st August 1913 Mass Of Perjuries Charged By Arnold Centers Hot Attack On Conley. Ridicules Prosecution Theory [Last Updated On: November 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: August 23rd, 2023]

- Friday, 22nd August 1913 Rosser Begins Final Plea [Last Updated On: February 17th, 2024] [Originally Added On: September 2nd, 2023]

- Sunday, 24th August 1913 Dorsey Demands Death Penalty For Frank In Thrilling Closing Plea [Last Updated On: November 16th, 2023] [Originally Added On: August 29th, 2023]

- Monday, 25th August 1913: Frank Case To Jury Today Leo Frank On His Way From Jail To Court, The Atlanta Georgian [Last Updated On: August 28th, 2024] [Originally Added On: September 3rd, 2023]

- Tuesday, 26th August 1913, Frank, Guilty On First Ballot [Last Updated On: February 17th, 2024] [Originally Added On: September 12th, 2023]

- Wednesday, 27th August 1913 Fight Begun To Save Frank Motion For New Trial Follows Death Sentence [Last Updated On: October 25th, 2024] [Originally Added On: September 12th, 2023]

- Thursday, 28th August 1913 Reply Made To Frank's Attack [Last Updated On: February 17th, 2024] [Originally Added On: September 17th, 2023]

- Monday, 1st September 1913: Scent Phagan Case In Woman’s Cries Building Ransacked, The Atlanta Georgian [Last Updated On: November 23rd, 2024] [Originally Added On: November 23rd, 2024]

- Tuesday, 2nd September 1913: Mystery At Frank's Pencil Plant Solved, The Atlanta Georgian [Last Updated On: November 23rd, 2024] [Originally Added On: November 23rd, 2024]

- Wednesday, 3rd September 1913: Big Tasks Await Slaton’s Return, The Atlanta Georgian [Last Updated On: November 23rd, 2024] [Originally Added On: November 23rd, 2024]

- Friday, 5th September 1913: Conley To Face Misdemeanor Charge Only, The Atlanta Georgian [Last Updated On: November 23rd, 2024] [Originally Added On: November 23rd, 2024]

- Sunday, 7th September 1913: Dorsey Sure He Can Break Frank Claim Of Jury Bias, The Atlanta Georgian [Last Updated On: November 23rd, 2024] [Originally Added On: November 23rd, 2024]

- Monday, 8th September 1913: Medical Student Is Held As Swindler, The Atlanta Georgian [Last Updated On: November 23rd, 2024] [Originally Added On: November 23rd, 2024]

- Tuesday, 9th September 1913: Jim Conley Indicted For Part In Phagan Killing, The Atlanta Georgian [Last Updated On: November 23rd, 2024] [Originally Added On: November 23rd, 2024]

- Thursday, 11th September 1913: Judge Roan Picked To Get Appointment To New Judgeship, The Atlanta Georgian [Last Updated On: November 23rd, 2024] [Originally Added On: November 23rd, 2024]

- Friday, 12th September 1913: Roan Likely To Be Named In 30 Days, The Atlanta Georgian [Last Updated On: November 23rd, 2024] [Originally Added On: November 23rd, 2024]

- Saturday, 13th September 1913: Attorneys Jab At Each Other's Face In Broyles' Court, The Atlanta Georgian [Last Updated On: November 23rd, 2024] [Originally Added On: November 23rd, 2024]

- Sunday, 14th September 1913: Professor Beavers To Teach Etiquette, The Atlanta Georgian [Last Updated On: November 23rd, 2024] [Originally Added On: November 23rd, 2024]

- Monday, 15th September 1913: Express Theft Arrest Due By Nightfull, The Atlanta Georgian [Last Updated On: November 23rd, 2024] [Originally Added On: November 23rd, 2024]

- Tuesday, 16th September 1913 No Judge To Try Fulton Docket [Last Updated On: September 6th, 2024] [Originally Added On: February 3rd, 2024]

- Wednesday, 17th September 1913 Conley To Fight Felon Charge Bitterly [Last Updated On: September 6th, 2024] [Originally Added On: February 3rd, 2024]

- Wednesday, 17th September 1913 Say Partee Shot In Self-defense [Last Updated On: April 26th, 2024] [Originally Added On: February 17th, 2024]

- Monday, 22nd September 1913 Judge Roan Not To Hear Frank Trial Motion [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: March 31st, 2024]

- Wednesday, 24th September 1913 Detective Black Not Blamed For Fighting [Last Updated On: September 6th, 2024] [Originally Added On: March 31st, 2024]

- Thursday, 25th September 1913 Recall To Apply To All Big Offices [Last Updated On: September 6th, 2024] [Originally Added On: March 31st, 2024]

- Friday, 26th September 1913 Judge Roan To Hear Arguments Asking Retrial For Frank [Last Updated On: September 6th, 2024] [Originally Added On: February 29th, 2024]

- Sunday, 28th September 1913 Judge Hill May Hear Frank Case [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: February 29th, 2024]

- Monday, 29th September 1913 Delay On Frank Hearing Seems Unavoidable [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: February 29th, 2024]

- Tuesday, 30th September 1913 Frank Ready For New Fight Rosser Ready. Roan Will Hear Frank Argument [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: February 29th, 2024]

- Wednesday, 1st October 1913: Rosser Ready Roan Will Hear Frank Argument, The Atlanta Georgian [Last Updated On: October 21st, 2024] [Originally Added On: August 9th, 2024]

- Thursday, 2nd October 1913: Ask New Frank Trial On 115 Counts Many Errors Laid To Court; Charge Made Of Jury Intimidation, The Atlanta Georgian [Last Updated On: October 21st, 2024] [Originally Added On: August 9th, 2024]

- Friday, 3rd October 1913: Frank Trial Juror Denies Charge Of Bias, The Atlanta Georgian [Last Updated On: October 21st, 2024] [Originally Added On: August 9th, 2024]

- Saturday, 4th October 1913: Sensational Charge In Frank Case, The Atlanta Georgian [Last Updated On: October 21st, 2024] [Originally Added On: August 9th, 2024]