Atlanta Constitution

August 5th, 1913

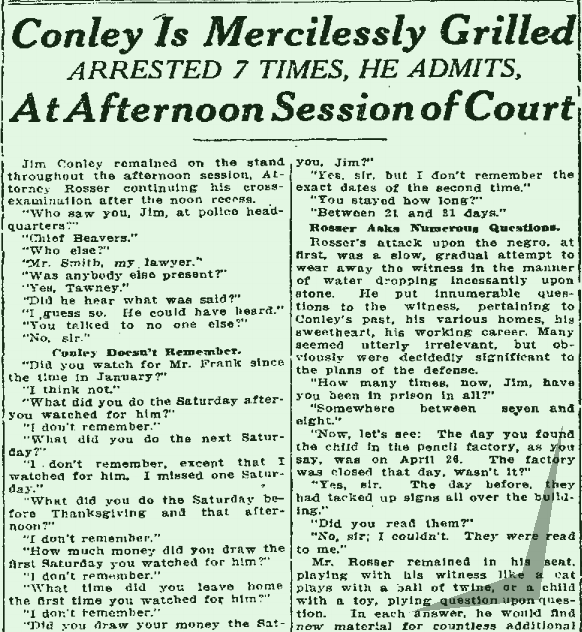

ARRESTED 7 TIMES, HE ADMITS

Jim Conley remained on the stand throughout the afternoon session. Attorney Rosser continuting his cross-examination after the noon recess.

"Who saw you, Jim, at police headquarters?"

"Chief Beavers."

"Who else?"

"Mr. Smith, my lawyer."

"Was anybody else present?"

"Yes, Tawney."

"Did he hear what was said?"

"I guess so. He could have heard."

"You talked to no one else?"

"No, sir."

Conley Doesn't Remember.

"Did you watch for Mr. Frank since the time in January?"

"I think not."

"What did you do the Saturday afternoon you watched for him?"

"I don't remember."

"What did you do the next Saturday?"

"I don't remember, except that I watched for him. I missed one Saturday."

"What did you do the Saturday before Thanksgiving and that afternoon?"

"I don't remember."

"How much money did you draw the first Saturday you watched for him?"

"I don't remember."

"What time did you leave home the first time you watched for him?"

"I don't remember."

"Did you draw your money the Saturday after Thanksgiving?"

"I don't remember."

"On the day before Thanksgiving, what time did you come to the factory?"

"I don't recollect exactly, Mr. Rosser."

"On the day after—did you see Frank?"

"Yes, sir."

Remembers Seeing Frank.

"You remember that, alright?"

"Yes, sir."

"Did you see Mr. Darley?"

"I don't think so."

"How many hours did you put in that day?"

"I don't recollect."

"Then, you don't know how much pay you drew, do you?"

"Yes, sir, I know how much Mr. Frank gave me for watching for him—a dollar and a quarter."

"You've already told about that."

"Yes, sir, I know it."

"Where did you live?"

"37 Bynum street."

"You've been in prison, haven't you, Jim?"

"Yes, sir."

"Do you remember the day you went to prison the first time and the day you got out?"

"No, sir; I don't."

"Did you ever live elsewhere than on Bynum street?"

"Yes, sir, 172 Rhodes street, near Electric avenue."

"You were in prison twice, weren't you, Jim?"

"Yes, sir, but I don't remember the exact dates of the second time."

"You stayed how long?"

"Between 21 and 31 days."

Rosser Asks Numerous Questions.

Rosser's attack upon the negro, at first, was a slow, gradual attempt to wear away the witness in the manner of water dropping incessantly upon stone. He put innumerable questions to the witness, pertaining to Conley's past, his various homes, his sweetheart, his working career. Many seemed utterly irrelevant, but obviously were decidedly significant to the plans of the defense.

"How many times, now, Jim, have you been in prison in all?"

"Somewhere between seven and eight."

"Now, let's see: The day you found the child in the pencil factory, as you say, was on April 26. The factory was closed that day, wasn't it?"

"Yes, sir. The day before, they had tacked up signs all over the building."

"Did you read them?"

"No, sir; I couldn't. They were read to me."

Mr. Rosser remained in his seat, playing with his witness like a cat plays with a ball of twine, or a child with a toy, plying question upon question. In each answer, he would find new material for countless additional questions, with which he sought to tangle Conley in his own narrative.

Many questions were asked of the negro regarding his associates of the street and fellow-workers in the pencil factory, most of which dealt with Gheron, "Snowball" Bailey, a negro youth who was once also under arrest in connection with the Mary Phagan murder during the early part of the investigation.

"When you were in prison, who took your place in the pencil factory, Jim?"

"I don't know, sir."

Sent Him to Stockade.

"What was the fine they imposed on you the last time you were sentenced?"

"They didn't give me no fine."

"You were one of the new darkeys in the factory, weren't you?"

"Yes, sir."

"When did you see Mr. Frank?"

"I don't remember."

"When was the first time he ever talked with you except on business?"

"I don't remember. He talked and jollied with me. He and Mr. Darley, both, jollied with me."

"Did he ever jolly with you before you watched for him?"

"Yes, sir, sometimes."

"Do you remember what he said?"

"No, sir."

"Who saw him ever jolly with you?"

"Mr. Darley and Mr. Schiff."

Questioned About Daisy Hopkins.

"When did Daisy Hopkins work at the pencil factory?"

"Some time in 1912."

"What floor did she work on?"

"The fourth floor."

"What part of 1912?"

"June on up."

"Has she ever worked there in 1913?"

"I don't know."

"Do you know where she lives?"

"No, sir."

"Is she married?"

"I don't know."

"What's the color of her hair?"

"Don't remember."

"What's the color of her complexion?"

"What's complexion?"

"You're dark complected—I'm white complected."

"Oh, she was white complected."

Just Ears Like Folks.

"What kind of ears did she have?"

"Ears like folks."

"I didn't expect her to have ears like a rabbit—small ears, big ears, or what?"

"Kinder small ears."

"How old was she?"

"About 22."

"How do you know she worked there in June, 1912?"

"I knew it was 1912, and one day she sent me down to the office with a note. It had ‘June' on it."

"I thought you couldn't read?"

"I could read ‘June' alright."

"How many times have you ever seen this man Dalton around the pencil factory?"

"Several times."

"On the third trip, of which you've started, how did he come to be at the factory?"

"Miss Daisy Hopkins brought him."

"How long has it been since you've seen Dalton?"

Saw Him at Police Station.

"About a month, I saw him down at police headquarters when they brought him in for me to identify him."

"Did you identify him?"

"Yes, sir."

"The first day you watched for Frank, did you see Mr. Holloway?"

"Yes, sir."

"Was he around the factory?"

"Yes, sir."

"What time did he leave?"

"About 2:30 o'clock."

"Did you see Mr. Darley?"

"Yes, sir."

"What time did he leave?"

"I don't know exactly—he was always leaving."

"The next time you watched for Mr. Frank, who did you see of the working force?"

"Mr. Holloway."

"What time did he leave?"

"About 2 o'clock."

Watched in September.

"Thanksgiving was the next time you watched for Mr. Frank, wasn't it?"

"No, it was some time in September."

"Was Mr. Darley around the factory?"

"I didn't see him."

"Mr. Schiff?"

"I think so."

"What time did Schiff leave?"

"I didn't know."

"Isn't it true that a lot of people are at work in the factory on Saturdays?"

"Yes, sir, sometimes."

"On Thanksgiving, did anybody work there all afternoon?"

"I don't remember."

"Isn't it true that Schiff was in the office?"

"I didn't see him."

Knows Part of Plant.

"You know the whole plant well, don't you?"

"Some parts of it I do—some parts I don't."

"How big a room, then, is Mr. Frank's office?"

"I don't know."

"It has two desks in it, hasn't it?"

"I think so."

"Who has the other desk?"

"Mr. Schiff."

"How long is the outside office?"

"I don't know."

"Is there a safe in the inside office?"

"Yes, sir."

"You can't see from the stairway into the inside office?"

"Yes, sir."

"Can a man sitting in the office see anyone coming up the stairs?"

"I don't know."

"But, Frank can't see folks coming along the floor unless they go past the clock?"

"If he is sitting at his desk, he can."

Conley Shown Diagram.

At this point, Conley was given a diagram to show the jury where he was sitting on the occasion of a certain talk with Frank near Frank's office.

"How much did you say you drank on Friday, April 25?"

"Not so very much."

"Do you know Detective Harry Scott?"

"Yes, sir."

"When you were at police headquarters, you told them that you got up at 9:30 a.m. on the morning of the 25th, didn't you?"

"Yes, sir."

"That wasn't so, was it?"

"No."

"Yet you looked them in the face and lied, didn't you?"

"Yes, sir."

"You also told them you went to Peters street?"

"Yes, sir."

"And didn't go?"

"Yes, sir. I went to Peters street, alright."

"How long did you stay on Peters street?"

"Not long."

"You stayed until 11 o'clock, didn't you?"

"No."

"You told Scott so, didn't you?"

"Don't remember about that."

Told Some Stories, He Admits.

"Do you remember what you told Harry Scott and John Black?"

"Not all."

"The truth is you lied all the way ‘round?"

"I told some stories, I'll admit."

"Didn't you make three affidavits, neither of which is true?"

"Some of them are true."

"But aren't they all lies?"

"No, there's a lot of truth in all of them."

Attorney Hooper objected to this question, saying the affidavits were in existence and that they should be shown the witness as prescribed by the law.

Negro Drilled, Says Arnold.

Attorney Arnold, in discussion, said: "It is easy to see that the negro has been canned and grilled and prepared for this business, and would easily recognize the affidavits. That is not what we want to do at present."

Hooper's retort was:

"Mr. Arnold, I do not think, was called upon to explain the history of the affidavits. They are here in the court, as requested, and the law demands that they be shown the witness. This is a new way of legislating. Should the law be changed just because these men get up and demand that their rights, and their right alone, prevail. This case should be tried entirely as any other case should be tried."

Solicitor Dorsey said:

"We submit that the remarks of Mr. Arnold be considered prejudicious—his remarks that the witness had been canned and prepared in a state satisfactory to the defense. I beg that the judge make a statement to that effect to the jury."

Arnold Attacks Dorsey.

Mr. Arnold rose again.

"My friend Dorsey, in his usual fussy, snarlish way, has accused me of being prejudicious. If we sought to impeach Jim Conley finally, we will put the affidavits into evidence. Each affidavit represents a world of pumping and labor on the part of detectives. We expect to show that the affidavits followed many contradictory statements, and that Conley never admitted anything until confronted with the fact that he could write."

Judge Roan sustained the defense.

"How long did the detectives talk to you?" Mr. Rosser continued with the witness.

"I don't remember."

"The first time you made a statement of your movements, Black and Scott were together, weren't they?"

"Yes, I think I sent for Mr. Black."

"Where were you when this statement was made?"

"In the detectives' office in the police station."

"How long did they talk to you?"

"For quite a while."

"Didn't you buy a pint of liquor on Peters street at 10 o'clock, Friday, the 25th?"

"No."

"What did you tell Black?"

"That I bought it about 10 o'clock, as you say."

"Didn't you tell him you left Rhodes street about 10 o'clock."

"No, sir."

"After you bought this liquor—"

Mr. Hooper interceded, saying:

An Attempt to Impeach.

"We have no objection to any of this going before the jury, but this procedure of Rosser's is only an attempt to impeach the witness, and it is in a manner against what is prescribed by the law. There is a rule against this method of his, and it is as plain as the nose on your face, your honor."

Mr. Rosser said:

"Now, it is to be said that I cannot ask this man what he said on a certain time? I've got a right to do it to test or refresh his memory."

Judge Roan, in answer, stated:

"This rule is universal. This man, Mr. Hooper, is your witness. The defense has ample grounds to test his memory."

Mr. Hooper replied:

"Does your honor hold that this examination is not solely for the purpose of impeachment?"

"I do not know what will be the ultimate result," said the judge.

Mr. Rosser's examination was resumed.

"That statement you made to Black, didn't you say in it that you bought the liquor after 11 o'clock? You went to the Butt-in saloon?"

"I said I went there before I bought the liquor."

"Didn't you tell Black and Scott that some things you told them were true and some were not?"

"No; they never asked me."

"Didn't you look them straight in the face and lie?"

He Hung His Head.

"No, sir. I hung my head whenever I told them a lie, and looked them straight in the face when I told them the truth. I thought I'd just tell a little bit of the truth, so Mr. Frank would get scared and would send somebody to come and get me out of trouble."

"Oh, well we'll get to that later on."

"How many saloons did you tell them you went to?"

"Three."

"Did you tell them that you went straight home from Peters street?"

"No, sir, I told them I hung around a while."

"What did you tell them about the money you had?"

"I told them something about $3.50 I had."

"Which one of the detectives told you to look him squarely in the face?"

"Nary a-one."

When Jim is Lying.

"What good does it do you to hang your head when you're not telling the truth?"

"None that I know of."

"What else do you do when you are lying?"

"Fool with my fingers."

"How long did the detectives talk to you—hours at a time?"

"Sometimes they'd talk to me for hours."

"Didn't John Black say you were a good nigger, and didn't Scott curse you?"

"No, sir—sometimes they'd sit and whisper together, but that's all."

"Didn't they put a negro in there with you?"

"Yes, sir."

"Didn't he ask you what you were in there for?"

"No, sir."

"Didn't you tell that darkey that you weren't worried—that you didn't know anything about the crime?"

"No, sir, I didn't tell him anything like that."

"On May 24, didn't you send for Black?"

"I don't remember, I don't know what date it was; it was when the papers put it in that I was down there suffering."

Mr. Dorsey objected, but was not sustained.

"I sent for Mr. Black," the negro continued, "and told him I would him. I told him I had held back part of it."

"You told Black you were going to tell part of the truth and hold back part of it?"

"Yes, sir."

"Was Mr. Scott there?"

"I don't remember, I didn't see him, I know."

"Did you tell them in the police station that you were telling only part of the truth?"

"No sir."

The Mysterious Notes.

"Do you remember what were on the notes you say you wrote for Mr. Frank on the day of the murder?"

"Yes, sir; something about a long, tall black negro doing it."

"In your verbal statement to Black—the first one—did you say anything about a girl being dead and toting her down into the basement?"

"I don't remember."

"In your second statement, did you say anything about this?"

"Yes, sir—I think I did. I think I remember saying something about it."

Mr. Dorsey objected to this on grounds of the statement in question being in writing, and in hands of the defense.

"Haven't we a right," he said, "to show a thing in writing as dictated by the law. Please take cognizance of the fact that we have produced these papers at their request. Then, does your honor tell me he does not know the statements are in writing, and give us no opportunity to refresh the memory of the witness. If there is any doubt in your honor's mind, then let us ask a question."

Rules for Defense.

"Suppose the affidavits contradict the statement of the witness?" replied Judge Roan. "In which case the defense would have grounds for testing the witness' memory. The man says he can't write, and did not write it himself. Does the law, in such a case, say that his memory may not be tested to oral statement he has made for transcription?"

His ruling was to the effect that the defense could ask the question which had formerly been put.

In the midst of this heated clash […]

CONLEY IS GRILLED AT AFTERNOON SESSION

[…] between counsel for the defense and counsel for the state, Solicitor Dorsey attempted to read a portion of a state statute for the judge's benefit. Judge Roan, as the solicitor spoke, turned to talk with a spectator who had climbed to the bench. The solicitor recited only three words from the book, caught sight of the judge's apparent disinterest, and threw down the volume with a deprecatory gesture of resignation.

"Now, Jim," continued Mr. Rosser, "whenever you are lying or telling the truth, please be so kind as to give me some signal. Did you say anything about going into the basement in that second statement?"

"I don't remember."

"You said you were going to keep back some of it—what was it?"

"The best part."

At this juncture, when it was seen that the court was preparing to adjourn for the afternoon, Mr. Arnold arose, saying:

"We make a motion that the court take charge of this negro, Jim Conley, and let the sheriff put him in custody. The law requires such a move, and I ask your honor to do this fair and square thing. Not to let a soul talk with him, not even the sheriff."

No Objection by State.

In reply to this, Mr. Hooper stated: "So far as the state is concerned, no objection can be voiced on our part, that is, if he is put there no one at all can get to him."

Judge Roan said:

"Mr. Sheriff, no one is to get to this witness, not even you."

Attorney William M. Smith, counsel for Conley, who had mounted a seat in the jury box, vacated several moments previously, broke in:

"My connection with Jim Conley is solely for the safeguard of truth. I have full confidence in Sheriff Mangum, but there is no way in the county jail to keep persons from Conley in case he is placed therein, or, unless a special man is appointed to keep guard over him. I ask for an additional guard for his benefit. Also, he needs special food after the ordeal of this afternoon. Frank is enjoying special meals, is allowed better fare than any of the other prisoners, and I ask the same for Conley."

Sheriff Mangum assured the court that special pains would be taken for the negro, and that he would be sufficiently guarded. He left the courthouse in the sheriff's charge.

* * *

- Monday, 28th April 1913 Girl is Assaulted and then Murdered in Heart of Town [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 5th, 2021]

- Monday, 28th April 1913 Mullinax Held in Phagan Case [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 4th, 2021]

- Tuesday, 29th April 1913 $1,000 Reward [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: November 30th, 2021]

- Tuesday, 29th April 1913 “Every Woman and Girl Should See Body of Victim and Learn Perils” [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 3rd, 2021]

- Tuesday, 29th April 1913 I Am Not Guilty, Says John M. Gantt [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2021]

- Tuesday, 29th April 1913 Pinkertons Hired to Assist Police Probe the Murder of Mary Phagan [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 2nd, 2021]

- Tuesday, 29th April 1913 Was Victim of Murder Lured Off on Joy Ride Before She Met Death? [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: November 29th, 2021]

- Tuesday, 29th April 1913 Who Saw Pretty Mary Phagan After 12 OClock on Saturday? [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: November 28th, 2021]

- Wednesday, 30th April 1913 City to Offer $1,000 for Slayers Arrest [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: November 23rd, 2021]

- Wednesday, 30th April 1913 Did Murderers Plan Cremation? [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: November 19th, 2021]

- Wednesday, 30th April 1913 Factory Clock Not Punched for Hours on Night of Murder [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: November 26th, 2021]

- Wednesday, 30th April 1913 Gantt Turned Over to Sheriff of Fulton [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: November 20th, 2021]

- Wednesday, 30th April 1913 Inquest This Morning. [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: November 27th, 2021]

- Wednesday, 30th April 1913 Leo M. Frank Holds Conference With Lee [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: November 25th, 2021]

- Wednesday, 30th April 1913 Mayor Confers with Chief; Says Extras are Misleading [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: November 22nd, 2021]

- Wednesday, 30th April 1913 Murder Analyzed By Dr. MKelway [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: November 21st, 2021]

- Wednesday, 30th April 1913 Shot Fired Near Lee May Break His Nerve [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: November 18th, 2021]

- Wednesday, 30th April 1913 While Hundreds Sob Body of Mary Phagan Lowered into Grave [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: November 24th, 2021]

- Thursday, 1st May 1913 City Offers $1,000 Reward for Capture of Phagan Slayers [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: November 16th, 2021]

- Thursday, 1st May 1913 Frank Not Apparently Nervous Say Last Men to Leave Factory [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: November 15th, 2021]

- Thursday, 1st May 1913 Frank Tried to Flirt With Murdered Girl Says Her Boy Chum [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: November 17th, 2021]

- Thursday, 1st May 1913 Girl Was Dead Ten Hours Before Her Body Was Found [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: November 13th, 2021]

- Thursday, 1st May 1913 Has a New Explanation [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: November 11th, 2021]

- Thursday, 1st May 1913 Newt Lee Tells His Story During Morning Session [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: November 14th, 2021]

- Thursday, 1st May 1913 Pretty Young Sweetheart Comes To the Aid of Arthur Mullinax [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: November 12th, 2021]

- Friday, 2nd May 1913 Frank and Lee Held in Tower; Others Released [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: November 10th, 2021]

- Saturday, 3rd May 1913 Not Guilty, Say Both Prisoners [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: November 9th, 2021]

- Sunday, 4th May 1913 Impostors Busy in Sleuth Roles in Phagan Case [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: November 8th, 2021]

- Sunday, 4th May 1913 The Case of Mary Phagan [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: November 7th, 2021]

- Monday, 5th May 1913 Sleuths Believe They Can Convict Phagan Murderer [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: November 6th, 2021]

- Monday, 5th May 1913 Women Inspectors Urged to Protect Factory Girls [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: November 5th, 2021]

- Tuesday, 6th May 1913 Pistol Toting is Condemned by Judge Ellis in His Charge [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: November 2nd, 2021]

- Tuesday, 6th May 1913 Probe Phagan Case Grand Jury Urged [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: November 3rd, 2021]

- Tuesday, 6th May 1913 Third Man Brought into Phagan Mystery by Frank’s Evidence [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: November 4th, 2021]

- Wednesday, 7th May 1913 Detective Chief Fired for Arresting Bowen as a Phagan Suspect [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: October 31st, 2021]

- Wednesday, 7th May 1913 Officials Plan to Exhume Body of Victim Today [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: November 1st, 2021]

- Thursday, 8th May 1913 Frank Will Take Stand at Inquest [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: October 29th, 2021]

- Thursday, 8th May 1913 Greeks Make Protest [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: October 28th, 2021]

- Thursday, 8th May 1913 Stains of Blood on Shirt Fresh, Says Dr. Smith [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: October 30th, 2021]

- Friday, 9th May 1913 Frank and Lee Ordered Held by Coroner’s Jury for Mary Phagan Murder [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: October 27th, 2021]

- Friday, 9th May 1913 Woman’s Handkerchief Brought to Officers [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: October 26th, 2021]

- Saturday, 10th May 1913 Girl Will Swear Office of Frank Deserted Between 12:05 and 12:10 [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: October 25th, 2021]

- Sunday, 11th May 1913 Mystery of 14-Year-Old Mary Phagans Tragic End Adds One to Long List of Atlantas Unsolved Crimes [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: October 23rd, 2021]

- Sunday, 11th May 1913 Officer Swears He Found Frank With Young Girl [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: October 24th, 2021]

- Monday, 12th May 1913 Find Guilty Man, Franks Lawyer Told Pinkertons [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: October 22nd, 2021]

- Monday, 12th May 1913 The Phagan Case Day by Day [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: October 21st, 2021]

- Tuesday, 13th May 1913 My Son Innocent, Declares Mother of Leo M. Frank [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: October 20th, 2021]

- Tuesday, 13th May 1913 Mystery Within a Mystery Now Baffling Newspaper Men Working on the Phagan Case [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: October 19th, 2021]

- Wednesday, 14th May 1913 Clue is Sought in Handwriting of Mary Phagan [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: October 18th, 2021]

- Thursday, 15th May 1913 Victim of Murder Prepared to Die, Believes Dorsey [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: October 17th, 2021]

- Friday, 16th May 1913 Coming of Burns is Assured, Says Colonel Felder [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: October 16th, 2021]

- Friday, 16th May 1913 Constitution Starts Fund to Bring Burns Here to Solve the Mary Phagan Murder Mystery [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: October 15th, 2021]

- Saturday, 17th May 1913 In Loop of Death Dorsey May Have Clue to Murderer [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: October 14th, 2021]

- Sunday, 18th May 1913 Three Arrests Expected Soon in Phagan Case [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: October 13th, 2021]

- Monday, 19th May 1913 Detectives Seek Clue in Writing of Negro Suspect [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: October 12th, 2021]

- Tuesday, 20th May 1913 Women Declare Phagan Murder Must Be Solved [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: October 11th, 2021]

- Wednesday, 21st May 1913 Tobie is Studying Mary Phagans Life [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: October 10th, 2021]

- Thursday, 22nd May 1913 Experts Are Here on Finger Prints [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: October 9th, 2021]

- Friday, 23rd May 1913 Rooming House Sought by Frank Declares Woman [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: October 8th, 2021]

- Saturday, 24th May 1913 A. S. Colyar Makes Answer to Charges of Col. Felder [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: October 1st, 2021]

- Saturday, 24th May 1913 Bribery Charges False Declares Col. Felder; Calls Them Frame-Up [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: October 6th, 2021]

- Saturday, 24th May 1913 Career of A. S. Colyar Reads Like Some Story In the Arabian Nights [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: October 5th, 2021]

- Saturday, 24th May 1913 Chief Beavers Not Surprised at Col. Felders Statements [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: September 30th, 2021]

- Saturday, 24th May 1913 Coleman Affidavit Which Police Say Felder Wanted [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: October 3rd, 2021]

- Saturday, 24th May 1913 Felder is Charged with Bribe Offer for Phagan Papers [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: September 28th, 2021]

- Saturday, 24th May 1913 Frank Not Home Hours on Saturday Declares Lanford [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: October 7th, 2021]

- Saturday, 24th May 1913 Girl Strangled, Says Indictment [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: September 29th, 2021]

- Saturday, 24th May 1913 Mayor Woodward Reported Caught by the Dictograph Seeking Police Evidence [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: October 4th, 2021]

- Saturday, 24th May 1913 Solicitor General Dorsey Talks of the Bribe Charge [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: October 2nd, 2021]

- Sunday, 25th May 1913 Becker of South Lanford is Branded by Col. Tom Felder [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: September 27th, 2021]

- Sunday, 25th May 1913 C. W. Tobie, Burns Agent, Tells of the Conferences He Held With A. S. Colyar [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: September 14th, 2021]

- Sunday, 25th May 1913 Charge Framed Up by a Dirty Gang [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: September 18th, 2021]

- Sunday, 25th May 1913 Colyar a Success in Preacher Role [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: September 26th, 2021]

- Sunday, 25th May 1913 Colyar Declared Criminal and Not Worthy of Belief in Four Sworn Statements [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: September 17th, 2021]

- Sunday, 25th May 1913 Felders Charges of Graft Rotten [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: September 19th, 2021]

- Sunday, 25th May 1913 Frank Indicted in Phagan Case [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: September 21st, 2021]

- Sunday, 25th May 1913 Frank is Praised by John O. Parmele [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: September 16th, 2021]

- Sunday, 25th May 1913 Frank the Guilty Man, Declares Chief Lanford [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: September 22nd, 2021]

- Sunday, 25th May 1913 Here Is the Dictagraph Record of Woodwards Conversation [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: September 15th, 2021]

- Sunday, 25th May 1913 Knew It Was Coming, Declares Cole Blease [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: September 23rd, 2021]

- Sunday, 25th May 1913 Others Will Be Involved In New Bribery Charges Intimates Chief Lanford [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: September 20th, 2021]

- Sunday, 25th May 1913 Police Chairman Confident of Honesty of Officials [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: September 25th, 2021]

- Sunday, 25th May 1913 Says Chief is Able to Care for Himself [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: September 24th, 2021]

- Sunday, 25th May 1913 Thomas Felder Brands the Charges of Bribery Diabolical Conspiracy [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: September 13th, 2021]

- Monday, 26th May 1913 Frank is Guilty, Says Pinkerton [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: September 11th, 2021]

- Monday, 26th May 1913 New Witnesses in Phagan Case Found by Police [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: September 12th, 2021]

- Monday, 26th May 1913 Thousands in Atlanta Living the Life of Mary Phagans MurdererRev. W. W. Memminger [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: September 10th, 2021]

- Tuesday, 27th May 1913 Burns Agency Quits the Phagan Case; Tobie Leaves Today [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: September 9th, 2021]

- Tuesday, 27th May 1913 Chief James L. Beavers Reply to Mayor Woodward [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: September 8th, 2021]

- Wednesday, 28th May 1913 Conley Reported to Admit Writing Notes Saturday [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: September 7th, 2021]

- Thursday, 29th May 1913 Negro Sweeper Tells the Story of Murder Notes [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: September 6th, 2021]

- Friday, 30th May 1913 But One Thing is Proved in Mary Phagan Mystery [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: September 4th, 2021]

- Friday, 30th May 1913 Conley Says He Helped Frank Carry Body of Mary Phagan to Pencil Factory Cellar [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: September 5th, 2021]

- Saturday, 31st May 1913 Conley Tells Graphic Story of Disposal of the Dead Body [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: September 2nd, 2021]

- Saturday, 31st May 1913 Mary Phagans Murder Was Work of a Negro Declares Leo M. Frank [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: September 3rd, 2021]

- Sunday, 1st June 1913 Conley is Removed from Fulton Tower at His Own Request [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: September 1st, 2021]

- Monday, 2nd June 1913 Frank Asked Room to Conceal Body Believes Lanford [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: August 31st, 2021]

- Tuesday, 3rd June 1913 Grand Jury Calls for Thos. Felder and Police Heads [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: August 30th, 2021]

- Tuesday, 3rd June 1913 Leo Franks Cook Put Under Arrest [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: August 29th, 2021]

- Wednesday, 4th June 1913 Servant of Frank is Liberated After Long Examination [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: August 27th, 2021]

- Wednesday, 4th June 1913 Vice List Wanted by Chief Beavers; Promises Probe [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: August 28th, 2021]

- Thursday, 5th June 1913 Frank Wanted Gun to Take His Life, Says Negro Cook [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: August 26th, 2021]

- Thursday, 5th June 1913 Jury Will Probe Dictagraph Row [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: August 25th, 2021]

- Friday, 6th June 1913 Dorsey Replies to the Charges of Mrs. L. Frank [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: August 24th, 2021]

- Friday, 6th June 1913 Felder and Lanford Come Near to Blows [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: August 21st, 2021]

- Friday, 6th June 1913 Grand Jury May Drop Vice Probe [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: August 23rd, 2021]

- Friday, 6th June 1913 Grand Jury Probes Detective Leaks [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: August 22nd, 2021]

- Saturday, 7th June 1913 Current in Effect on Day of Tragedy [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: August 19th, 2021]

- Saturday, 7th June 1913 Lanford Claps Lid on Detective News [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: August 20th, 2021]

- Sunday, 8th June 1913 Felder Makes Answer to Dictagraph Episode [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: August 18th, 2021]

- Sunday, 8th June 1913 Lanford Answers Felder’s Charge [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: August 17th, 2021]

- Tuesday, 10th June 1913 Leo Frank Reported Ready for His Trial [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: August 16th, 2021]

- Wednesday, 11th June 1913 Dictograph Records Crooked, Says Gentry [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: August 15th, 2021]

- Wednesday, 11th June 1913 Lanford Silent on Rosser’s Card [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: August 14th, 2021]

- Thursday, 12th June 1913 Grand Jury Will Probe Affidavits About Dictagraph [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: August 13th, 2021]

- Friday, 13th June 1913 Beavers Trying to Find Gentry [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: August 12th, 2021]

- Friday, 13th June 1913 Negro Conley May Face Frank Today [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: August 11th, 2021]

- Saturday, 14th June 1913 Col. Felder Asks Early Jury Probe [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: August 9th, 2021]

- Saturday, 14th June 1913 Conley Released, Then Rearrested [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: August 10th, 2021]

- Sunday, 15th June 1913 Detective Chief Tells Grand Jury of “Third Degree” [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: August 8th, 2021]

- Sunday, 15th June 1913 Frank Hooper Aids Phagan Prosecution [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: August 7th, 2021]

- Sunday, 15th June 1913 Solicitor Dorsey Goes to New York [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: August 6th, 2021]

- Monday, 16th June 1913 Col. Thomas Felder Goes to Cincinnati [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: August 5th, 2021]

- Monday, 16th June 1913 Constitution Picture Will Figure in Trial [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: August 4th, 2021]

- Wednesday, 18th June 1913 Two New Witnesses Sought by Officers [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: August 3rd, 2021]

- Thursday, 19th June 1913 Mrs. Formby Here for Phagan Trial [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: August 2nd, 2021]

- Thursday, 19th June 1913 Reuben Arnold May Aid Frank’s Defense In Big Murder Trial [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: August 1st, 2021]

- Friday, 20th June 1913 Formby Woman May Not Be A Witness [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: July 31st, 2021]

- Saturday, 21st June 1913 Postponement Likely In Leo Frank’s Trial [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: July 30th, 2021]

- Sunday, 22nd June 1913 Col. Felder Returns From Trip to Ohio [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: July 28th, 2021]

- Sunday, 22nd June 1913 Frank Not Guilty of Phagan Murder Declares Arnold [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: July 29th, 2021]

- Sunday, 22nd June 1913 Leading Law Firms Have Joined Forces [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: July 27th, 2021]

- Monday, 23rd June 1913 Leo M. Frank’s Trial June 30, Says Dorsey [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: July 26th, 2021]

- Tuesday, 24th June 1913 Frank’s Trial Set For Next Monday [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: July 25th, 2021]

- Wednesday, 25th June 1913 Reported Hoke Smith May Aid Leo Frank [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: July 24th, 2021]

- Wednesday, 25th June 1913 Trial of Leo Frank Postponed by Judge [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: July 23rd, 2021]

- Saturday, 28th June 1913 Lanford and Felder Indicted for Libel [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: July 22nd, 2021]

- Friday, 4th July 1913 Effort Will Be Made to Free Newt Lee [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: July 20th, 2021]

- Wednesday, 9th July 1913 Caught Drinking, Three Policemen Fired Off Force [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: July 19th, 2021]

- Wednesday, 9th July 1913 Vice Scandal Probe Postponed for a Day [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: July 18th, 2021]

- Thursday, 10th July 1913 Hotels Involved By Story of Vice Young Girl Tells [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: July 17th, 2021]

- Thursday, 10th July 1913 Mary Phagan’s Pay Envelope is Found [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: July 16th, 2021]

- Friday, 11th July 1913 Conley Not Right Man, Says Mincey [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: July 15th, 2021]

- Sunday, 13th July 1913 Detective Harry Scott’s Hunch Thrilling Story of How it Secured James Conley’s Confession [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: July 12th, 2021]

- Sunday, 13th July 1913 Former Story True, Says Negro Sweeper [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: July 14th, 2021]

- Sunday, 13th July 1913 Lee Must Remain Behind the Bars [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: July 13th, 2021]

- Sunday, 13th July 1913 Parents Are Blamed for Daughters’ Fall [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: July 11th, 2021]

- Wednesday, 16th July 1913 No New Indictment Says Jury Foreman [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: July 10th, 2021]

- Friday, 18th July 1913 Many Rumors Afloat Regarding Grand Jury [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: July 8th, 2021]

- Friday, 18th July 1913 Wordy War Over, Says Woodward [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: July 9th, 2021]

- Saturday, 19th July 1913 Grand Jury Meets to Indict Conley [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: July 6th, 2021]

- Saturday, 19th July 1913 Scott Believes Conley Innocent, Asserts Lanford [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: July 7th, 2021]

- Saturday, 19th July 1913 Woodward Uses Clemency Again [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: July 5th, 2021]

- Sunday, 20th July 1913 Frank's Lawyers Score Dorsey For His Stand [Last Updated On: October 18th, 2024] [Originally Added On: March 31st, 2024]

- Sunday, 20th July 1913 Frank’s Lawyers Score Dorsey for His Stand [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: July 4th, 2021]

- Sunday, 20th July 1913 Grim Justice Pursues Mary Phagan’s Slayer [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: July 2nd, 2021]

- Sunday, 20th July 1913 Mrs. Nina Formby Will Not Return for Trial [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: July 3rd, 2021]

- Sunday, 20th July 1913 Prison System of Georgia Attacked by Episcopalians [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: July 1st, 2021]

- Tuesday, 22nd July 1913 Date Of Frank Trial Depends On Weather [Last Updated On: October 13th, 2024] [Originally Added On: March 31st, 2024]

- Wednesday, 23rd July 1913 Bloody Club Lends New Clue to Mystery [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: June 28th, 2021]

- Wednesday, 23rd July 1913 Give Right of Way to Case of Frank [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: June 29th, 2021]

- Wednesday, 23rd July 1913 Mayor May Hold Up Dictagraph Warrant [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: March 8th, 2024]

- Thursday, 24th July 1913 Conley and Lee Meet in Tower [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: June 27th, 2021]

- Thursday, 24th July 1913 Is It Lady-like To Look Like A Lady On Atlanta's Streets? [Last Updated On: October 15th, 2024] [Originally Added On: March 31st, 2024]

- Thursday, 24th July 1913 Phagan Mystery Club Examined by Experts [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: June 26th, 2021]

- Friday, 25th July 1913 Chiefs Will Probe Removal of Conley [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: June 24th, 2021]

- Friday, 25th July 1913 Try to Corroborate Story Told by Conley [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: June 22nd, 2021]

- Friday, 25th July 1913 Veniremen Drawn for Frank Trial [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: June 25th, 2021]

- Friday, 25th July 1913 Work on Phagan Case Brings Promotion to Pinkerton Man [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: June 23rd, 2021]

- Saturday, 26th July 1913 Frank’s Lawyers Ready for Trial [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: June 21st, 2021]

- Sunday, 27th July 1913 All in Readiness for Frank’s Trial Monday Morning [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: June 30th, 2021]

- Monday, 28th July 1913 Jurors in Leo M. Frank Case Must Answer Four Questions [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: June 19th, 2021]

- Monday, 28th July 1913 Leo Frank’s Trial on Murder Charge Booked for Today [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: June 20th, 2021]

- Tuesday, 29th July 1913 96 Men are Called Before Getting Jury [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: June 14th, 2021]

- Tuesday, 29th July 1913 Burglars Try to Enter Home of Frank Juror [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: June 17th, 2021]

- Tuesday, 29th July 1913 Mincey, on Arrival Reaffirms Affidavit, The Atlanta Constitution [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: June 16th, 2021]

- Tuesday, 29th July 1913 Numerous Witnesses Called in Frank Case [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: June 15th, 2021]

- Tuesday, 29th July 1913 Reporter Witnesses are Allowed in Court [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: June 13th, 2021]

- Tuesday, 29th July 1913 Trial of Leo M. Frank on Charge of Murder Begins; Mrs. Coleman, George Epps and Newt Lee on Stand [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: June 18th, 2021]

- Tuesday, 29th July 1913 Unusual Interest Centers In Mrs. Frank’s Appearance [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: June 12th, 2021]

- Tuesday, 29th July 1913 Watchman Tells Of Finding Body Of Mary Phagan [Last Updated On: October 18th, 2024] [Originally Added On: March 22nd, 2024]

- Tuesday, 29th July 1913 Will Leo Frank’s Lawyers Put Any Evidence Before the Jury? [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: June 11th, 2021]

- Wednesday, 30th July 1913 Clash Comes Over Evidence Of Detective John Starnes [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: June 8th, 2021]

- Wednesday, 30th July 1913 First Two Days of Frank Trial Only Skirmishes Before Battle [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: June 4th, 2021]

- Wednesday, 30th July 1913 Lee, Dull and Ignorant, Calm Under Gruelling Cross Fire [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: June 9th, 2021]

- Wednesday, 30th July 1913 Mother and Daughter in Tears As Clothing of Mary Phagan Is Exhibited in Courtroom [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: June 5th, 2021]

- Wednesday, 30th July 1913 Officer Tells About Discovery Of Body of Girl in Basement [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: June 6th, 2021]

- Wednesday, 30th July 1913 Sergeant Dobbs Resumes Stand At Tuesday Afternoon Session [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: June 7th, 2021]

- Wednesday, 30th July 1913 Three Witnesses Describe Finding Mary Phagan’s Body [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: June 10th, 2021]

- Thursday, 31st July 1913 Bearing of Black and Lee Forms a Study in Contrast [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: May 27th, 2021]

- Thursday, 31st July 1913 Daintily Dressed Girl Tells Of Daily Routine of Factory [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: May 30th, 2021]

- Thursday, 31st July 1913 Defense Riddles John Black’s Testimony [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: June 3rd, 2021]

- Thursday, 31st July 1913 Detective Black Muddled By Keen Cross-Examination Of Attorneys for Defense [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: June 2nd, 2021]

- Thursday, 31st July 1913 Gantt, Once Phagan Suspect, On Stand Wednesday Afternoon [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: May 28th, 2021]

- Thursday, 31st July 1913 Idle and Curious Throng Court Despite Big Force of Deputies [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: May 31st, 2021]

- Thursday, 31st July 1913 Mrs. Coleman Is Recalled To Identify Mary’s Handbag [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: June 1st, 2021]

- Thursday, 31st July 1913 Photo By Francis E Price, Staff Photographer. [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: March 31st, 2024]

- Thursday, 31st July 1913 Rogers on Stand Describes Visit of Frank to Undertakers [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: May 29th, 2021]

- Thursday, 31st July 1913 William Gheesling First Witness Today [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: May 26th, 2021]

- Friday, 1st August 1913 Acquitted In The Same Court, She Believers Is Innocent [Last Updated On: October 18th, 2024] [Originally Added On: March 22nd, 2024]

- Friday, 1st August 1913 Attorneys for Both Sides Riled by Scott’s Testimony; Replies Cause Lively Tilts [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: May 25th, 2021]

- Friday, 1st August 1913 Blood Found by Dr. Smith on Chips and Lee’s Shirt [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: May 17th, 2021]

- Friday, 1st August 1913 E. F. Holloway Testimony [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: May 21st, 2021]

- Friday, 1st August 1913 Finding of Hair and Envelope Described by Factory Machinist [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: May 20th, 2021]

- Friday, 1st August 1913 Frank’s Presence in Office at Time He Says He Was There is Denied by Girl on Stand [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: May 22nd, 2021]

- Friday, 1st August 1913 Haslett Describes Visit to Home of Leo Frank [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: May 19th, 2021]

- Friday, 1st August 1913 Holloway Denies Affidavit He Signed for Solicitor [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: May 24th, 2021]

- Friday, 1st August 1913 Leo Frank Innocent, Says Mrs. Appelbaum [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: May 18th, 2021]

- Friday, 1st August 1913 Mrs. Arthur White Takes Stand Today [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: May 15th, 2021]

- Friday, 1st August 1913 Sweeper Swears No Spots Were on Floor Day Before Murder [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: May 16th, 2021]

- Friday, 1st August 1913 William Gheesling, Embalmer, Tells of Wounds on Girl’s Body [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: May 23rd, 2021]

- Saturday, 2nd August 1913 Frequent and Angry Clashes Between Attorneys Mark the Hearing of Darley’s Testimony [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: May 13th, 2021]

- Saturday, 2nd August 1913 Gay Febuary Tells Frank Jury About Statement Prisoner Made [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: May 6th, 2021]

- Saturday, 2nd August 1913 Husband of Minola McKnight Describes Movements of Frank [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: May 9th, 2021]

- Saturday, 2nd August 1913 Mary Phagan Murdered Within Hour After Dinner [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: May 14th, 2021]

- Saturday, 2nd August 1913 Negro Lurking in Factory Seen by Wife of Employee [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: May 11th, 2021]

- Saturday, 2nd August 1913 Policeman W. F. Anderson Tells of Newt Lee’s Telephone Call [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: May 10th, 2021]

- Saturday, 2nd August 1913 Startling Statements Made During Testimony of Dr. Harris [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: May 12th, 2021]

- Saturday, 2nd August 1913 Stenographer Parry Identifies Notes Taken at Phagan Inquest [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: May 8th, 2021]

- Saturday, 2nd August 1913 Witnesses Called To Stand To Testify Against Frank [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: March 13th, 2024]

- Saturday, 2nd August 1913 Women and Girls Thronging Court for Trial of Leo Frank [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: May 7th, 2021]

- Sunday, 3rd August 1913 Break in the Frank Trial May Come With the Hearing Of Jim Conley’s Testimony [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: May 2nd, 2021]

- Sunday, 3rd August 1913 Chief Beavers Tells of Seeing Blood Spots on Factory Floor [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: April 26th, 2021]

- Sunday, 3rd August 1913 Condition of Girl’s Body Described by Dr. J. W. Hurt [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: May 3rd, 2021]

- Sunday, 3rd August 1913 Detective Waggoner Describes Extreme Nervousness of Frank [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: May 1st, 2021]

- Sunday, 3rd August 1913 Dorsey Pleased With Progress [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: April 25th, 2021]

- Sunday, 3rd August 1913 Finding of Dead Girl’s Parasol is Told by Policeman Lasseter [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: April 29th, 2021]

- Sunday, 3rd August 1913 Fixing Hour of Girl’s Death Through Aid of Modern Science The Prosecution’s Greatest Aid [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: April 30th, 2021]

- Sunday, 3rd August 1913 Girl Asked for Mary Phagan’s Pay But Was Refused by Frank [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: April 28th, 2021]

- Sunday, 3rd August 1913 Good Order Kept in Court by Vigilance of Deputies [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: April 27th, 2021]

- Sunday, 3rd August 1913 Mistrial Near When Jury Saw a Newspaper in Judge’s Hands [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: May 5th, 2021]

- Sunday, 3rd August 1913 Resume of Week’s Evidence Shows Little Progress Made [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: May 4th, 2021]

- Monday, 4th August 1913 Dr. H. F. Harris Will Take Stand This Afternoon [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: April 23rd, 2021]

- Monday, 4th August 1913 Every Man on Franks Jury Gets Nickname for Trial [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: April 22nd, 2021]

- Monday, 4th August 1913 Frank on Stand Wednesday Week [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: April 24th, 2021]

- Monday, 4th August 1913 Leo Franks Trial Is Attracting Universal Interest in Georgia [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: April 21st, 2021]

- Monday, 4th August 1913 Their Testimony Is Important In The Trial Of Leo M. Frank [Last Updated On: October 13th, 2024] [Originally Added On: March 22nd, 2024]

- Tuesday, 5th August 1913 Amazing Testimony of Conley Marks Crucial Point of Trial; Says Frank Admitted Crime [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: April 19th, 2021]

- Tuesday, 5th August 1913 Conley Grilled Five Hours By Luther Rosser [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: April 20th, 2021]

- Tuesday, 5th August 1913 Flashlight in The Constitution Introduced in Trial of Frank [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: April 17th, 2021]

- Tuesday, 5th August 1913 Frank Very Nervous, Testifies L. O. Grice [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: April 13th, 2021]

- Tuesday, 5th August 1913 Handsome Woman Seeks in Vain For Witness at Franks Trial [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: April 14th, 2021]

- Tuesday, 5th August 1913 Scenes In Courtroom Monday While Conley Was On Stand [Last Updated On: October 13th, 2024] [Originally Added On: March 22nd, 2024]

- Tuesday, 5th August 1913 Stanford Recalled By Solicitor Dorsey [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: April 12th, 2021]

- Tuesday, 5th August 1913 Witnesses in Franks Trial In Role of Marriage Witnesses [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: April 16th, 2021]

- Tuesday, 5th August 1913 Women of Every Class and Age Listen With Morbid Curiosity To Testimony of Negro Conley [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: April 15th, 2021]

- Wednesday, 6th August 1913 Conley Remains Calm Under Grilling Cross-Examination [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: April 10th, 2021]

- Wednesday, 6th August 1913 Conleys Main Story Still Remains Unshaken [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: April 11th, 2021]

- Wednesday, 6th August 1913 Defense Asks Judge Roan to Strike From Records Part of Conley Testimony [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: April 8th, 2021]

- Wednesday, 6th August 1913 Ignorance of Negro Witnesses Helps Them When on the Stand [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: April 7th, 2021]

- Wednesday, 6th August 1913 Mincey Affidavit Is Denied By Conley During Afternoon [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: April 9th, 2021]

- Wednesday, 6th August 1913 Women Are Playing Big Part In Trial Of Frank [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: March 22nd, 2024]

- Thursday, 7th August 1913 Applause Sweeps Courtroom When Dorsey Scores a Point [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: April 2nd, 2021]

- Thursday, 7th August 1913 Because He is Patriotic Mincey is Here for Trial [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: April 1st, 2021]

- Thursday, 7th August 1913 Hugh Dorsey Wins His Spurs; Crowd Recognizes Gameness [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: March 30th, 2021]

- Thursday, 7th August 1913 Judges Decision Admits Conley Testimony in Full [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: March 31st, 2021]

- Thursday, 7th August 1913 Mary Phagan Was Strangled Declares Dr. H. F. Harris [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: April 4th, 2021]

- Thursday, 7th August 1913 Mrs. Coleman Tells of Cooking Cabbage for Dr. H. F. Harris [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: April 3rd, 2021]

- Thursday, 7th August 1913 Spontaneous Applause Greets Dorseys Victory [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: April 6th, 2021]

- Thursday, 7th August 1913 Their Testimony Will Have Direct Bearing On Leo Frank's Case [Last Updated On: August 6th, 2024] [Originally Added On: March 31st, 2024]

- Thursday, 7th August 1913 Unable to Shake Conleys Story Rosser Ends Cross-Examination [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: April 5th, 2021]

- Thursday, 7th August 1913 While Murder Trial Goes on Witnesses While Away Time With Old Camp Meeting Songs [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: March 29th, 2021]

- Friday, 8th August 1913 Dalton Corroborates Statements Contained in Conleys Testimony [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: March 28th, 2021]

- Friday, 8th August 1913 Defense May Call for Character Witnesses Today [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: March 24th, 2021]

- Friday, 8th August 1913 Dorsey Forces Childs to Admit Certain Portions of His Testimony Could Not Be Considered Expert [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: March 27th, 2021]

- Friday, 8th August 1913 Dr. Childs Differs with Harris As to Processes of Digestion [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: March 26th, 2021]

- Friday, 8th August 1913 Dr. Frank Eskridge Aiding Prosecution [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: March 23rd, 2021]

- Friday, 8th August 1913 Harris Sticks to Testimony As to Time of Girls Death [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: March 22nd, 2021]

- Friday, 8th August 1913 Rosser Swears Bludgeon Was Not In Factory Day After the Murder [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: March 20th, 2021]

- Friday, 8th August 1913 Scott Called by Defense To Refute Conleys Story [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: March 25th, 2021]

- Friday, 8th August 1913 Will Defense Put Character of Leo Frank Before Jury? [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: March 21st, 2021]

- Saturday, 9th August 1913 Civil Engineer and Photographer Tell of Making Plats and Photos [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: March 13th, 2021]

- Saturday, 9th August 1913 Conductor Also Swears Epps Boy Was Not on Car With Mary Phagan [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: March 16th, 2021]

- Saturday, 9th August 1913 Couldnt Locate Epps Boy When Wanted in Court [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: March 18th, 2021]

- Saturday, 9th August 1913 Defense Will Seek to Show That Mary Phagans Body Was Tossed Down a Chute in Rear of Pencil Factory And Not Taken Down by Elevator As the State Insists [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: March 19th, 2021]

- Saturday, 9th August 1913 Epps Boy Not With Mary Phagan, Declares Street Car Motorman [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: March 10th, 2021]

- Saturday, 9th August 1913 Harry Scott and Boots Rogers Recalled to Stand by the State [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: March 12th, 2021]

- Saturday, 9th August 1913 Hinchey Tells of Seeing Frank on Car on Day of the Murder [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: March 11th, 2021]

- Saturday, 9th August 1913 Holloway, Witness for Defense, Riddled By Cross-Examination [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: March 17th, 2021]

- Saturday, 9th August 1913 Hopkins Woman Denies Charges Made By Dalton and Jim Conley; Is Forced to Admit Untruths [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: March 14th, 2021]

- Saturday, 9th August 1913 N. V. Darley Denies Testimony Given by Conley and Dalton [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: March 15th, 2021]

- Saturday, 9th August 1913 Witness Admits Discrepancies in Model of Pencil Factory [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: March 9th, 2021]

- Sunday, 10th August 1913 Defense Will Renew Attack Upon Dr. Harris Testimony [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: March 6th, 2021]

- Sunday, 10th August 1913 Epps Boy Denies Trying to Avoid Being Called to the Stand Again [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: March 5th, 2021]

- Sunday, 10th August 1913 Frank A. Hooper Is Proving Big Aid to Solicitor Dorsey [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: March 3rd, 2021]

- Sunday, 10th August 1913 Introduction by Defense of Host Of Character Witnesses Probable [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: March 4th, 2021]

- Sunday, 10th August 1913 Is Defense Planning Telling Blow At Testimony Given by Jim Conley? [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: March 1st, 2021]

- Sunday, 10th August 1913 Reporter Makes Denial of Charge That Reports Have Been Flavored [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: February 28th, 2021]

- Sunday, 10th August 1913 Schiff Put on Stand to Refute Conley and Dalton Testimony [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: March 7th, 2021]

- Sunday, 10th August 1913 Schiff Testimony Contradicts That Given by Dalton and Negro Conley [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: March 8th, 2021]

- Sunday, 10th August 1913 Startling Testimony of Conley Feature of Trials Second Week [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: March 2nd, 2021]

- Monday, 11th August 1913 Jurors Have a Great Time Playing Jokes on Deputies [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: February 26th, 2021]

- Monday, 11th August 1913 Murder Evidence May Be Concluded by Next Saturday [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: February 27th, 2021]

- Tuesday, 12th August 1913 As the Very Wildest of Guessing Dr. Westmoreland Characterizes Testimony Given by Dr. Harris [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: February 20th, 2021]

- Tuesday, 12th August 1913 Defense Has Best Day Since Trial of Frank Began [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: February 25th, 2021]

- Tuesday, 12th August 1913 Dr. Hancock Called by Defense, Assails Dr. Harris Testimony [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: February 21st, 2021]

- Tuesday, 12th August 1913 Expert Flatly Contradicts The Testimony of Dr. Harris [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: February 24th, 2021]

- Tuesday, 12th August 1913 Franks Financial Sheet Would Take 3 Hours Work to Finish Joel Hunter [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: February 19th, 2021]

- Tuesday, 12th August 1913 Guesswork and Not Science Asserts Dr. J. C. Olmstead [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: February 22nd, 2021]

- Tuesday, 12th August 1913 Schiff Admits He Kept Conley Knowing He Was Worthless [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: February 23rd, 2021]

- Wednesday, 13th August 1913 Many Witnesses Take the Stand to Refute Points of Prosecution [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: February 18th, 2021]

- Thursday, 14th August 1913 Bitter Fight at Morning Session Over Testimony of Dr. Wm. Owen [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: June 29th, 2023]

- Thursday, 14th August 1913 Dr. William Owen Tells How Conleys Story Was Re-enacted [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: February 16th, 2021]

- Thursday, 14th August 1913 Financial Sheets Introduced At Frank Trial in Afternoon [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: July 3rd, 2023]

- Thursday, 14th August 1913 Former Office Boy Saw No Women With Frank on Thanksgiving Day [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: July 4th, 2023]

- Thursday, 14th August 1913 Lemmie Quinn is Severely Grilled by Solicitor Dorsey [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: July 2nd, 2023]

- Thursday, 14th August 1913 Lively Tilts Mark the Hearing Of Testimony of Dr. Kendrick [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: July 6th, 2023]

- Thursday, 14th August 1913 More Witnesses Are Called to Blacken Daltons Character [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: July 1st, 2023]

- Thursday, 14th August 1913 Mother of Frank Denounces Solicitor Dorsey in Court [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: February 17th, 2021]

- Thursday, 14th August 1913 Mrs. Rae Frank, Mother of Prisoner, Denounces Solicitor Hugh Dorsey [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: June 30th, 2023]

- Thursday, 14th August 1913 Quinn Intimates That Spots May Have Been on Floor for Months [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: July 5th, 2023]

- Thursday, 14th August 1913 Surprise Sprung by Introduction of Character Witnesses by Defense [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: February 15th, 2021]

- Friday, 15th August 1913 Cars Often Ahead of Schedule Declares a Street Car Man [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: June 20th, 2023]

- Friday, 15th August 1913 Character of Frank Good, So Many Witnesses Declare [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: June 21st, 2023]

- Friday, 15th August 1913 Defense Witness Admit Barrett is Sensible Fellow [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: June 11th, 2023]

- Friday, 15th August 1913 Eight Character Witnesses Come to Defense of Superintendent [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: June 9th, 2023]

- Friday, 15th August 1913 Elevator Made Loud Noise Said Employee of Pencil Company [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: June 13th, 2023]

- Friday, 15th August 1913 Factory Forewoman Swears Conley Said He Was Drunk on April 26 [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: June 25th, 2023]

- Friday, 15th August 1913 Factory Mechanic Tells of Blood on Floor From Mans Wounded Hand [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: June 18th, 2023]

- Friday, 15th August 1913 Frank in Jovial Mood While Poker Game Was Going on at His House on Night of 26th [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: June 14th, 2023]

- Friday, 15th August 1913 Frank Not Nervous on Night Of Murder Says Mrs. Ursenbach [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: June 23rd, 2023]

- Friday, 15th August 1913 Lawyers Appear Very Interested in Raincoat Lent to Leo M. Frank [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: June 10th, 2023]

- Friday, 15th August 1913 Many Men Swear to Good Character of Superintendent of Pencil Factory [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: June 28th, 2023]

- Friday, 15th August 1913 Milton Klein, Visitor of Frank, Is Grilled by Solicitor Dorsey [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: June 12th, 2023]

- Friday, 15th August 1913 Miss Eva May Flowers Did Not See Any Blood on Factory Floor [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: June 22nd, 2023]

- Friday, 15th August 1913 Mother-in-Law of Frank Denies Charges in Cooks Affidavit [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: June 27th, 2023]

- Friday, 15th August 1913 Pittsburg Witness Tells of Franks Standing in School [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: June 24th, 2023]

- Friday, 15th August 1913 Sig Montag Tells of Employment Of Detectives and Two Lawyers [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: June 17th, 2023]

- Friday, 15th August 1913 Sister of Mrs. Leo M. Frank Tells Jury About Card Game [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: June 26th, 2023]

- Friday, 15th August 1913 Two More Character Witnesses Are Introduced by the Defense [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: June 15th, 2023]

- Friday, 15th August 1913 Wife and Mother of Frank Are Permitted to Remain in Court [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: June 16th, 2023]

- Friday, 15th August 1913 Women Tell of Seeing Frank On Way to and From Factory On Day That Girl Was Murdered [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: June 19th, 2023]

- Saturday, 16th August 1913 Aged Negro Drayman Called As a Witness Against Conley [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: June 4th, 2023]

- Saturday, 16th August 1913 Both Wife and Phone, He Says, Are Expensive and Necessary [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: June 5th, 2023]

- Saturday, 16th August 1913 Credit Man is Put on Stand to Identify Franks Writing [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: June 6th, 2023]

- Saturday, 16th August 1913 Dorsey Questions Witness About Alleged Fund for Franks Defense [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: June 3rd, 2023]

- Saturday, 16th August 1913 Every Girl on Fourth Floor of Factory Will Go on Stand [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: June 2nd, 2023]

- Saturday, 16th August 1913 Factory Employees Testimony Causes Laughter in Court Room [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: June 7th, 2023]

- Saturday, 16th August 1913 Frank as Innocent as Angels Conley Told Her, Says Witness [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: May 25th, 2023]

- Saturday, 16th August 1913 Host of Witnesses Declare Franks Character to Be Good [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: June 1st, 2023]

- Saturday, 16th August 1913 Leo Frank Innocent, Said Conley, According to a Girl Operator [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: May 30th, 2023]

- Saturday, 16th August 1913 Maid in Schiff Home Tells of Phone Message From Frank [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: May 26th, 2023]

- Saturday, 16th August 1913 Miss Mary Perk Tells Jurymen She Believes Conley Is Guilty [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: May 29th, 2023]

- Saturday, 16th August 1913 Mother of Frank Takes Stand to Identify Letter Son Wrote [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: May 28th, 2023]

- Saturday, 16th August 1913 Mrs. Rae Frank Goes on Stand in Defense of Her Son [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: June 8th, 2023]

- Saturday, 16th August 1913 Never Saw Any Women in Office of Frank Says Negro Witness [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: May 31st, 2023]

- Saturday, 16th August 1913 Says Frank Broke Baseball Date Shortly After Girl Was Killed [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: May 23rd, 2023]

- Saturday, 16th August 1913 Still Another Office Boy Swears He Never Saw Women With Frank [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: May 24th, 2023]

- Saturday, 16th August 1913 Traveling Salesman for Montags Tells of Conversation With Frank [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: May 27th, 2023]

- Sunday, 17th August 1913 Prisoner’s Mother Questioned As to Wealth of Frank Family [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: July 8th, 2023]

- Sunday, 17th August 1913 That Pinkertons Double-Crossed Police, Dorsey Tries to Prove [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: July 7th, 2023]

- Monday, 18th August 1913 Frank May Tell Story To Jury On Stand Today [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: July 8th, 2023]

- Monday, 18th August 1913 Mary Phagan's Grandmother Dies After Dreaming Girl Was Living [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: July 9th, 2023]

- Monday, 18th August 1913 Men on Frank Jury Must Be Some Mighty Good Husbands Asserts the Deputy in Charge [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: July 9th, 2023]

- Tuesday, 19th August 1913 Books And Papers Put In Evidence By The Defense [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: July 9th, 2023]

- Tuesday, 19th August 1913 Climax of Trial Reached When Frank Faced Jury [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: July 12th, 2023]

- Tuesday, 19th August 1913 Frank Ends Statement After Testifying Four Hours [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: July 25th, 2023]

- Tuesday, 19th August 1913 Frank's Character Is Testified To By Long List Of Girls [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: July 25th, 2023]

- Tuesday, 19th August 1913 Harlee Branch Tells Of Conley Pantomine [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: July 25th, 2023]

- Tuesday, 19th August 1913 Mrs. Wardlaw Denies Ever Seeing Frank On Car With Little Girl [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: July 25th, 2023]

- Wednesday, 20th August 1913 Clashes Between Lawyers Mark Effort To Impeach Negro Cook [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: July 25th, 2023]

- Wednesday, 20th August 1913 Denies He Said He Was Willing To Lead Party To Lynch Frank [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: July 25th, 2023]

- Wednesday, 20th August 1913 Dr. Clarence Johnson Is Called To Corroborate Dr. Roy Harris [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: July 25th, 2023]

- Wednesday, 20th August 1913 Saw Mary Phagan On Her Way To Pencil Factory, Says Mccoy [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: July 25th, 2023]

- Wednesday, 20th August 1913 Sideboard In Leo Frank's Home Moved, Asserts Husband Of Cook [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: July 25th, 2023]

- Wednesday, 20th August 1913 State Is Hard Hit By Judge Ruling Barring Evidence Attacking Frank [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: July 12th, 2023]

- Wednesday, 20th August 1913 State Suffers a Severe Blow When Testimony Is Ruled Out [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: July 12th, 2023]

- Wednesday, 20th August 1913 Witness Swears He Saw Frank Forcing Unwelcome Attentions Upon the Little Phagan Girl [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: July 24th, 2023]

- Thursday, 21st August 1913 Frank Hooper Opens Argument In Leo Frank Case This Morning [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: July 20th, 2023]

- Thursday, 21st August 1913 Frank’s Character Bad Declare Many Women and Girls on Stand [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: July 12th, 2023]

- Thursday, 21st August 1913 Girls Testify to Seeing Frank Enter Dressing Room With Woman [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: July 12th, 2023]

- Thursday, 21st August 1913 Girls Testify to Seeing Frank Talking to Little Mary Phagan With His Hands on Her Person [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: July 20th, 2023]

- Thursday, 21st August 1913 Leo Frank Takes Stand Again Despite Objection of Dorsey [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: July 20th, 2023]

- Thursday, 21st August 1913 Railway Employee Swears Car Reached Center of City at 12:03 [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: July 20th, 2023]

- Thursday, 21st August 1913 Starnes Tells How Affidavit From Negro Cook Was Secured [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: July 19th, 2023]

- Thursday, 21st August 1913 Swears That Frank Prepared Sheets in Less Than 2 Hours [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: July 12th, 2023]

- Thursday, 21st August 1913 Testimony of Dr. Harris Upheld By Noted Stomach Specialists [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: July 19th, 2023]

- Thursday, 21st August 1913 Testimony of Hollis Assaulted by Witness [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: July 19th, 2023]

- Friday, 22nd August 1913 Arnold Ridicules Plot Alleged By Prosecution And Attacks The Methods Used By Detective [Last Updated On: July 12th, 2024] [Originally Added On: July 26th, 2023]